by Julia Rosen Monday, June 8, 2015

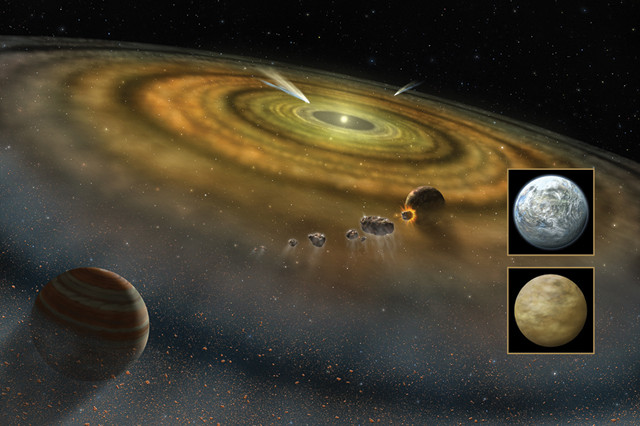

Computer technology is just one of the tools used by science illustrators, including Lynette Cook, whose conception of the dust and gas disk surrounding the star Beta Pictoris is shown here. Credit: NASA/FUSE/Lynette Cook.

Until a few decades ago, illustrators most often plied their trade with pencil and paper, ink, watercolors, or maybe airbrushed paints. While some still work in these media, most now rely heavily on computers, at least for the finished product. Some artists, like New Jersey-based illustrator Frank Ippolito, made the switch early on. “The promise was already there, so I was one of those early adopters who jumped in with both feet,” he says. For others, going digital became a necessity when clients started changing their expectations, says Lynette Cook, who previously worked as an artist and photographer at the Morrison Planetarium at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco.

The most common digital tools include Photoshop, and increasingly, 3-D modeling, which allows illustrators to approach subjects from different angles and to create more accurate, realistic images. “We have very high standards now for our visual effects,” says Robert Hurt, a visualization scientist for NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif.

The best computer graphics in the world come from the television and movie industry, says Horace Mitchell, director of the Science Visualization Studio at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. So, Mitchell’s team uses the same tools that Hollywood does to create stunning images and videos, including an animation program called Maya and a Pixar product called RenderMan.

Early science illustrators worked with much more rudimentary tools, including woodcuts, like this cow from "Historiae animalium," one of the first encyclopedias of zoology based on scientific observation, which was compiled by 16th-century Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner. Credit: public domain.

Although digital tools require more investment than traditional media, and perhaps some additional training, some illustrators also see practical benefits. “Going digital made things so much easier,” says Texas-based illustrator Pat Rawlings. Revising used to mean sketching or painting a subject over and over, and sending it back to scientists and editors for comments. Now, he says, “you can do really radical changes down to the last 30 minutes before you submit it.” And then, illustrators just shoot off an email. “No more putting things in FedEx and shipping them across the country,” Cook says.

But there’s still a place for old-fashioned art skills. “I think a lot on paper,” Ippolito says, especially for hard-to-grasp subjects. “There, it’s almost a ghost you are pursuing.”

And illustrators still need to hone their aesthetic sensibilities, which for the students of Ann Caudle, director of the Science Illustration Graduate Certificate program at California State University at Monterey Bay, means starting with the basics. A computer is “a big tool in the toolbox of the science illustrator,” she says, but “it can’t replace drawing skills.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.