by Lisa Song Thursday, January 5, 2012

The lush green backyard of a Beaufort, S.C., manor. Water is not usually a big concern in the southeastern United States. Nate Burgess, AGI

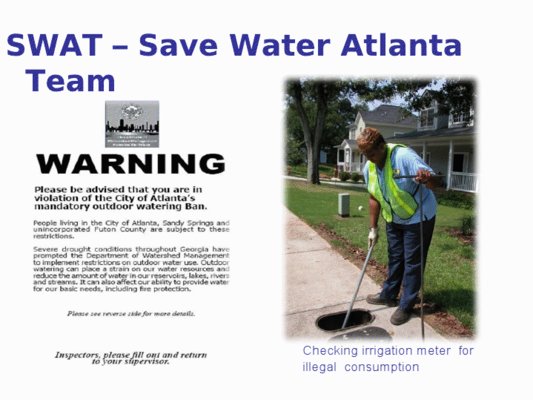

A member of SWAT (Save Water Atlanta Team) conducts a water meter investigation. City of Atlanta Department of Watershed Management

A 1930s advertisement on a streetcar in Denver, Colo. Water has been a concern in Denver since the town was founded. Denver Water

A Denver Water employee conducts an irrigation audit. Denver Water

Filled recharge basin in Tucson in January 2009. Lisa Song

A dry recharge basin in Tucson, Ariz., in March 2009. Tucson collects water in these basins for future use. Lisa Song

On a clear day in November 2007, the governor of Georgia held an unusual public vigil. Before the doors of his state capitol, Gov. Sonny Perdue bowed his head, took his wife’s hand and prayed for rain.

Some called it a stunt. Others admired the gesture. Above all, one thing was clear: Northern Georgia was facing its worst drought in 100 years, and there was no easy fix. It would take unprecedented statewide efforts to save Georgia from ruin.

With an average of 125 centimeters of rain a year, Georgia seems an unlikely place for a drought. Even in 2006 when the drought began, nearly 105 centimeters fell on the state. But Georgia’s water supply relies heavily on its system of reservoirs, which is entirely dependent on rain, and the state’s population growth — 18 percent between 2000 and 2008 (twice the national average) — only made matters worse. By late 2007, the city of Athens was down to six weeks of water. And Lake Lanier, the main reservoir for the Atlanta area, had four months before running dry.

Georgia’s situation is not unique. In recent years, severe droughts have hit most of the continental United States, starting with the Great Plains and Gulf Coast in 2006, then shifting to the West and Southeast in 2007 and 2008. Further exacerbating the problem is the development associated with a growing population. Every new road and driveway creates another hard surface funneling rain into storm sewers, leaving less water to seep into the soil, flow into rivers or replenish aquifers.

“In the end, it doesn’t matter if you’re in a wet area or a dry area,” says Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute, a research organization in Oakland, Calif., that studies water and global sustainability. “If you’re not careful about water management, eventually you’re going to run into limits.”

Fortunately, cities across the United States are investigating ways to improve their water management practices — and some of these tactics may serve as models for the rest of the country.

Drought isn’t Atlanta’s only water woe. A U.S. district court ruling in July 2009 threatens to cut off the city’s main source of water: Lake Lanier.

That ruling is the latest outbreak of the “tri-state water war” between Alabama, Florida and Georgia. It began in the 1940s, when the U.S. Congress authorized the construction of Lake Lanier by damming the Chattahoochee River. The federal reservoir was intended for hydropower, flood control and navigation purposes. Drinking water was deemed an “incidental” benefit, and Atlanta did not help pay for the project.

Over time, metro Atlanta (which includes the city and 15 surrounding counties) became increasingly dependent on the water released from the dam. This came at the expense of downstream states — among other uses, the river cools a major nuclear power plant in Alabama and sustains oyster farming in Florida. The legal battles began in 1990, pitting states, counties and hydropower companies against each other in a fight to control the river.

In 2003, a temporary 20-year agreement between Georgia and the Army Corps of Engineers (which operates the dam) reallocated 22 percent of the lake’s total conservation storage (the amount of water allocated for hydropower, navigation, recreation, irrigation and wildlife) for yearly water supply. Alabama challenged the agreement, setting off another series of legal cases. By law, all “major” operational changes on the lake require congressional approval, and in 2009 the judge handed Georgia an ultimatum: Unless Congress reauthorizes the lake for use as a water supply, the state will lose most of its Lanier privileges in three years. Georgia intends to appeal the ruling, and plans are under way to seek congressional reauthorization.

Faced with a drought and the potential loss of its main reservoir, Atlanta has started taking control of its water problems. Regions in a water crisis often turn to conservation: In the mid-1990s, New York City launched a low-flow toilet rebate program that saved 70 million gallons of water per day. In the 1970s, California adopted the “If it’s yellow let it mellow, if it’s brown flush it down” mantra to promote conservation. And parts of the arid Southwest have long adopted water conservation as a way of life. But despite repeated droughts in the 20th century, by 2001, only half the districts in metro Atlanta had water conservation programs.

Then in 2003, the city launched a leak-reduction program. Utilities replaced old water mains and sped up leak detection and repairs from 700 a year to 750 per month. Within five years, Atlanta had cut leakage rates from 20 percent to 15 percent, saving enough water to accommodate 244,000 new residents. That’s significant, given that the metro population grew from 4 million in 1998 to 5 million in 2008.

The city also sought to conserve water by changing how its citizens pay for it. Nine years ago, much of metro Atlanta still used declining block rate structures: Water use was divided into tiers by volume, much like income tax brackets, and customers in the upper tiers were charged less money per gallon for the extra water. But by 2009, nearly all of metro Atlanta had switched to conservation pricing, where the price per gallon increases with volume. The region also aims to cut per-capita water use by 20 percent (with respect to 2001 numbers) by 2035 by distributing low-flow retrofit kits, providing commercial water audits and increasing educational outreach.

Meanwhile, the intense drought showed no signs of letting up. In September 2007, Georgia was panicked enough to declare a level-4, or exceptional, drought, banning all outdoor watering. A month later, the state added a mandatory 10 percent reduction in water consumption. These restrictions remained in place well into 2008. As the heat of August wilted flowerbeds and neighbors snitched on illicit lawn-watering activities, an extraordinary thing happened: Atlanta met — and exceeded — conservation expectations. Under normal conditions, the city’s summertime use nears 110 million gallons of water a day. In August 2008, that number dropped to 90 million gallons. It took another year — until June 2009 — before the drought was officially declared over and the restrictions lifted.

Since the drought began, “every time we host a workshop on rain barrels or water conservation, they’re just bursting at the seams,” says Janet Ward, public relations manager for the City of Atlanta’s Department of Watershed Management. “People are becoming aware that just because we’re no longer in a level-4 drought doesn’t mean the situation couldn’t return and be just as serious.”

“We should not be resting on any laurels of what we have done at this point,” says Sally Bethea, executive director of Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper in Atlanta, a nonprofit that works to protect the river. Indoor water use for the average metro Atlanta resident is 70 gallons per day; in Germany, it’s 33 — so there’s a lot of work to be done. Additionally, Bethea says, the conservation numbers can be misleading. For instance, 15,000 homes retrofitted old plumbing systems in 2008. That may sound impressive, she says, but at this rate it would take decades to retrofit the close to 1 million metro homes that need the same service.

Furthermore, Gleick notes, “there’s a difference between conservation and efficiency.” Although the terms are often used interchangeably, “conservation” applies more to limiting water use, while “efficiency” is about reducing waste. “If conservation to Atlanta simply means banning outdoor car washing, then they’re not doing a good job,” he says. “What they need to implement are permanent improvements in efficiency, [such as] trashing inefficient toilets and washing machines, putting covers on pools, fixing sprinklers that water the sidewalks … If they can improve efficiency, then it doesn’t matter if there’s a drought.”

Los Angeles, for example, used less water in 2007 than it did in the late 1980s, despite adding a million more people. The city distributes low-flow toilets, promotes rain barrels and recycles irrigation water. “It’s possible to have a growing population and declining water use without hurting your economy,” Gleick says.

Metro Atlanta could save $300 million to $700 million by taking full advantage of its “hidden reservoir” of efficiency, notes a 2008 report from American Rivers, a Washington, D.C.-based organization dedicated to river conservation. That cost is calculated against the price of building new reservoirs to expand the water supply. Since the Lanier ruling, it’s a topic that’s suddenly on everyone’s minds.

“The truth is, Georgia didn’t have much of an incentive [to conserve in the past],” Gleick says. “So I actually think this court ruling provides a pretty clear call to them to rethink and expand their conservation and efficiency programs.”

Georgia’s nascent conservation movement could learn from a veteran by going West, beyond the Mississippi and over the Plains, to a place where 105 centimeters of rain would be an apocalyptic flood.

In Denver, Colo., a semi-arid environment, droughts can be expected when annual precipitation barely tops 35 centimeters. As early as the 1930s, city ads promoted efficient water use. More recently, the region has seen explosive population growth. Between 1990 and 2000, the number of Denver residents rose by more than 18 percent (while the nation as a whole grew 13 percent); and in 2009, Denver became the 24th largest city in the U.S.

After a severe drought in 2002, Denver Water (the city’s primary water utility) launched a conservation and efficiency program. By 2016, the utility declared, their customers’ total water use will be cut by 22 percent. And as of 2009, they’ve reached a 19 percent reduction.

“A lot of cultural change has occurred since the drought,” says Melissa Elliott, Denver Water’s conservation manager. “We wanted to capture that energy [from conserving during drought] and keep it while lessening restrictions and adding more incentives.” In that vein, Elliott says, the utility identified customers who were using more water than necessary, alerted them to their inefficient habits (sometimes face-to-face), and helped them become more efficient.

One of the most visible differences between Denver and Atlanta is xeriscaping, or landscaping with minimal water use. Single-family homes can use more than half of their water on outdoor care. Whereas the suburbs of Atlanta are aglitter with green lawns, in Denver, it’s common to see cacti alternating with sedums and native flowers. These drought-tolerant yards are especially popular in new developments and suburban commercial districts.

“Denver Water actually coined the term ‘xeriscaping’ in the 1980s. Our green industry [landscapers, lawn and garden companies] embraces the concept,” Elliott says. Xeriscaped yards take just as much work to maintain as traditional lawns. The trend is evident throughout the Southwest. Albuquerque, N.M., for example, gives water bill rebates to “xeric” customers; Las Vegas, Nev., pays residents up to $1.50 per square foot to rip out their green lawns.

Such a proposal would hardly fly in Georgia, land of lily ponds and blossoming magnolias (see sidebar). But for Denver and other parts of the arid Southwest, such landscaping can make a big difference.

Despite its landscaping and conservation success, Denver’s water woes are far from over. The city derives most of its supply from Rocky Mountain snowmelt, which feeds into a network of local rivers. As the region warms under climate change, snowmelt is arriving earlier, coming sooner at the rate of one week every 10 years, says Marc Waage, manager of Water Resource Planning for Denver Water. This means heavier streamflow in spring but drier creeks in late summer. However, some climate change scenarios predict more precipitation for the Denver region. The net effect in the future is quite uncertain, Waage says. But regardless of rainfall, water demand will increase with warming temperatures.

The future looks worse for cities like Albuquerque and Tucson, Ariz. Most climate change projections show increasing aridity for Southwestern states like Arizona and New Mexico, says Nolan Doesken, Colorado’s state climatologist based in Fort Collins, Colo. To compensate, Albuquerque, for example, has established an ambitious plan to cut water use by 40 percent before 2014. Tucson, meanwhile, has decided to “bank” water by pouring it into the desert.

West of Tucson, in the Central Avra Valley, are 11 recharge basins dug into the sandy ground. On any given day, at least some of them will be sparkling with deep blue water. The city sits atop an enormous reserve of groundwater, so the water in these basins flows downward to “recharge” the underground aquifer. The concept may sound simple, but the history of Tucson’s recharge basins is as complex as the winding canal that supplies the basins with water from the Colorado River.

Tucson used to be entirely dependent on groundwater. For decades, the city pumped its wells and the water gushed up. Then came the post-World War II population boom, when the Tucson metropolitan area grew from 45,000 people in 1950 to 213,000 in 1960. By the 1960s, the city’s water table was dropping by almost a meter a year. Parts of Tucson were subsiding, sinking as groundwater pumping allowed the pore space in subsurface rocks to collapse. In its most spectacular form, subsidence led to fissures, cracks in the earth that split and grew into dirt trenches three meters wide and more than 50 meters long.

In its search for more water, the city turned to the Colorado River, 540 kilometers away. For $4 billion, Tucson helped build the Central Arizona Canal in 1973, connecting the river to Phoenix, Tucson and other cities. When construction finished in 1992, residents along the canal paid for their share of river water. Tucson Water, the city’s largest water utility, ordered an annual amount of 136,000 acre-feet (one acre-foot is enough water to fill half an Olympic-sized swimming pool, or the equivalent of covering an acre of land in 12 inches of water). For the first time in history, Tucson’s residents could drink from a source other than the shrinking aquifer beneath their feet.

But “within a couple of weeks [of receiving the river water], my daughter was saying that the water at her school was rusty,” says Molly McKasson, former Tucson city council member. Pipes exploded. Faucets gushed water the color of red tea. The corrosive river water had stripped rust from the inside of pipes, and Tucson’s water treatment plant was malfunctioning. For a city raised on groundwater so pristine that it tasted almost sweet, this was unacceptable, McKasson says. Fourteen thousand complaints poured through the utility’s hotline. Residents began buying bottled water, or strained their taps with cheesecloth. Two years later, the mayor and city council closed the treatment plant, and Tucson returned to drinking pure groundwater. The following year, McKasson helped lead the charge to pass Proposition 200, banning the direct delivery of Colorado River water into Tucson.

Nonetheless, the city still needed the water source; so Tucson Water turned to a form of indirect delivery called artificial recharge. For $80 million, they dug recharge basins into Avra Valley. The Colorado River water would flow into the basins and trickle down through the porous subsurface, mixing with the native groundwater before pumps delivered the hybrid water into homes. It was a dilute cocktail, palatable for the standards of Tucson’s “spoiled” residents, says Wally Wilson, lead hydrologist at Tucson Water. And that’s what the city relies on today.

Recharge offers certain treatment advantages. About 80 percent of the water’s organic carbon content is removed as it flows downward through layers of sand and gravel, so by the time it is pumped back to the surface, the river water needs much less disinfection. The idea of recharge can also have a cleansing effect; some residents felt better knowing that their water was being treated “naturally” through underground percolation, Wilson says.

In addition, the basins serve as a buffer for drought. Because more water is coming into the basins than is pumped out, “we can bank water that we don’t need today,” Wilson notes. On average, the basins store 30,000 acre-feet a year. And all that water is replenishing the depleted aquifer: In 2001, the water table beneath the basins was 115 meters deep; by early 2009, the water table had risen to 91 meters.

Tucson isn’t the only city to use artificial recharge. Five more such projects are scattered throughout Arizona, all to replenish groundwater and store it for future droughts. When the 2009 recession forced Tucson Water to slash millions from the budget, the utility temporarily stopped recharging. That water didn’t go to waste — it was snatched up by the town of Gilbert (near Phoenix) and other buyers, each intent on securing water for the future. Meanwhile, Tucson’s recharge basins dwindled into dry pits, weeds sprouting from the cracked desert dirt. If all goes well, the city can start recharging again in 2010.

Tucson Water is also determined to expand its recharge facilities in the next few years, Wilson says. Construction is under way on a new series of basins. With both sets working at capacity, Tucson could accommodate nearly double its annual share of the Colorado River. That extra water would come from a variety of new sources; Tucson Water could lease extra river water from Indian reservations or local farmers. Whatever the future source, the basins would be able to hold it.

Despite preparing for the future, water remains a top concern for Atlanta, Denver, Tucson and cities across the United States. “Water’s a constant worry,” says Julia Fonseca, environmental planning manager for Pima County, Ariz., which includes Tucson. The top 10 fastest-growing states, which include Arizona, Colorado and Georgia, have all been victim to drought in the past decade. Whether cities in the future choose to conserve through efficiency or come up with creative ways to store water for eventual shortages, it’s never too early to get in the race. As Gleick warns, “No matter where you are, you’d better start thinking about smart, efficient use of your water resources.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.