by Harvey Leifert Tuesday, September 2, 2014

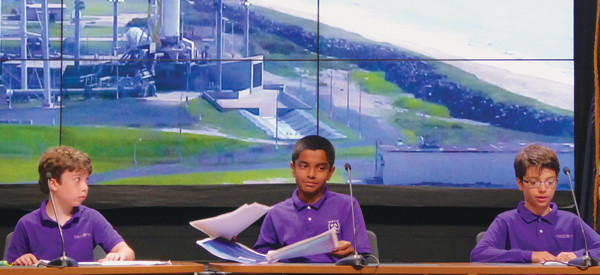

Three fifth graders from New York City's NEST+m School describe their bread mold experiment, which is aboard the Orb-2 mission, seen on the screen behind them. Credit: Harvey Leifert.

As Orb-2, the latest mission to resupply the International Space Station (ISS), lifted off on July 13, no one at NASA’s Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport on Wallops Island, Va., was more thrilled than 16 elementary and high school students whose scientific experiments were on board the Cygnus spacecraft. The fifth through 12th graders represented 15 teams totaling 99 students from across the United States whose proposals had survived a rigorous screening program.

The competitive procedure was comparable to what adult scientists face when competing for scarce time on a research telescope or in a specialized lab, according to Jeff Goldstein, who created the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program (SSEP) in 2010. From the 1,344 proposals submitted by teams comprising 6,750 students, regional and then national review committees selected the 15 experiments to fly aboard Cygnus in a payload unit named “Charlie Brown” in homage to the Apollo 10 command module.

Sixteen elementary and high school students represented all 99 who planned the 15 experiments aboard Orb-2. They briefed the media at Wallops Island just hours before launch. Credit: Harvey Leifert.

The space agency is fully on board with student participation, to the point that NASA Administrator Charles Bolden addressed and met with the students at a media briefing four hours prior to launch. Noting that his own fifth-grade science class had been limited to setting off baking soda volcanoes, the former astronaut praised the young experimenters as the next generation of American scientists and engineers.

Cygnus delivered 1,650 kilograms of cargo to the ISS, mainly food, clothing, repair and replacement parts, and a number of tiny satellites, called CubeSats, to be deployed into space. About one kilogram of the payload was the box carrying the 15 student experiments. Each is contained in a transparent silicone tube, measuring 170 millimeters in length by 13 millimeters in diameter. Created by NanoRacks, which also developed the CubeSats, the tubes are known as Fluids Mixing Enclosure (FME) Mini-Labs and can each be divided into two or three areas using clamps.

Parents and teachers, as well as reporters, were impressed by the student presentations. Credit: Harvey Leifert.

The students’ challenge was to devise experiments, typically involving mixing substances, to demonstrate the effect of weightlessness on various biological, physical and chemical processes. Astronauts are tasked with removing and replacing clamps and in some cases shaking the tubes, allowing mixing to occur and stop at designated times. As controls, the students mimic these procedures in “ground-truth experiments” on Earth. When the space experiment FMEs return to Earth — astronauts will bring them back in October — they will be sent to the student scientists for comparison with their ground-truth versions. Differences in results between the two sets can be attributed to the microgravity environment of the ISS.

Among the youngest students at the Wallops Island briefing were three fifth graders from New York City’s NEST+m School. Their project — no mixing involved — is called “What is the effect of microgravity on mold growth on white bread?” They are using an FME containing a morsel of bread, which won’t be disturbed or manipulated on board the ISS. As the students described it to reporters, on Earth, mold dust in the air settles on bread due to gravity. In space, they hypothesize, the mold may remain suspended in the air and not affect the bread, or not as much. When the two samples are compared, they will measure the area of mold on each, and compare the color of the mold and of the bread.

Fluid Mixing Enclosures like this 170-millimeter-long sample were at the heart of the student experiments. Clamps allow astronauts to separate the tubes into two or three compartments for controlled mixing of ingredients. Credit: Harvey Leifert.

Eleventh-grade students at Montachusett Regional Vocational Technical School in Fitchburg, Mass., designed an experiment that does involve mixing. They are seeking to monitor the production of antibiotics produced from Bacillus subtilis in microgravity, to learn whether the antibiotic could be produced on board a spacecraft during a long-term manned mission. They placed a freeze-dried sample of the microbe in the center section of their FME tube. On one side is a growth medium and on the other side a growth inhibitor, both clamped off from the center section. Two weeks before departure from the ISS in October, an astronaut will remove one clamp, allowing the growth medium to mix with the microbe sample. After mixing, the clamp will be replaced, making two identical chambers of microbes plus medium. Then, two days before return to Earth, an astronaut will remove the other clamp, allowing the growth inhibitor to enter one of the chambers only. The high school students hope to learn whether B. subtilis can be preserved and reactivated as necessary in this fashion, in order to help protect the health of future space voyagers.

NASA Administrator Charles Bolden expressed admiration for the creativity of the student projects. The former astronaut conducted experiments himself while aboard the International Space Station. Credit: Harvey Leifert.

“This is how real research proceeds, from opportunity, to defining a proposed research program, to submission of a proposal, to formal proposal review and selection” by a review board, Goldstein tells students on SSEP’s website. The final review board for SSEP’s Mission 5, the one launched on July 13, was a diverse group of 17 scientists from leading institutions representing a variety of specialties, including oncology, planetary science, astrophysics, biology, biochemistry, geology and science education.

Even as the student experiments recently carried to the ISS were underway, SSEP was in the process of evaluating proposals for student experiments to be carried aboard Mission 6, tentatively scheduled for October, and it has given advance notice for opportunities aboard Mission 7, in the spring of 2015. “The idea,” Goldstein told EARTH, “is that such experiences need to be part of the curriculum, so that students can see research for themselves, and so science education is not simply about teaching a book of knowledge.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.