by Steve Murray Thursday, December 14, 2017

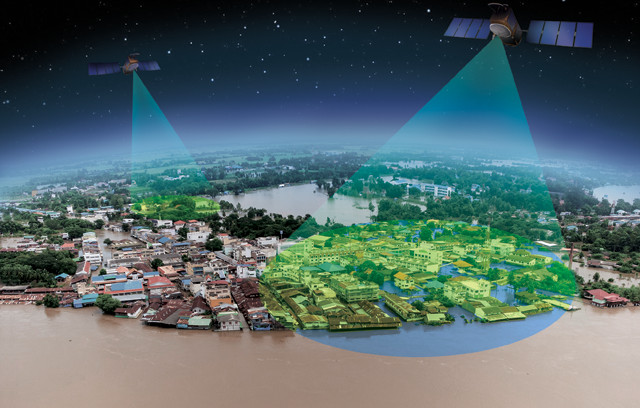

Through its SERVIR program, NASA is putting geospatial satellite images and analysis tools into the hands of local decision-makers around the world to help them address natural disasters and the effects of climate change. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI (base image: ©iStockphoto.com/sushi7688).

Life is tightly linked to weather in the Lower Mekong countries of Southeast Asia, and the weather is rarely still. In 2016, the Mekong River was at its lowest level since 1926 as the region endured the second season of its worst drought in 90 years. The drought was felt across Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam, jeopardizing exports like rice, seafood and fruit. In 2015, the Thailand Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives even asked rice farmers to delay their early summer planting because of water shortages, a move with big financial risks.

The sea added to the economic pain, intruding through canals and rivers into low-lying lands, increasing the salinity levels in agricultural soil and further threatening crop yields.

Only a year later, severe rains caused floods in Thailand that soaked 7,000 square kilometers of paddy fields. An October flood in Vietnam — the fourth since July — destroyed more than 34,000 houses and impacted 4,800 square kilometers of land.

Extreme fluctuations like these disrupt communities in many ways, and both governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) of the Mekong region are looking for solutions. SERVIR, a unique partnership between the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and NASA, is now providing them.

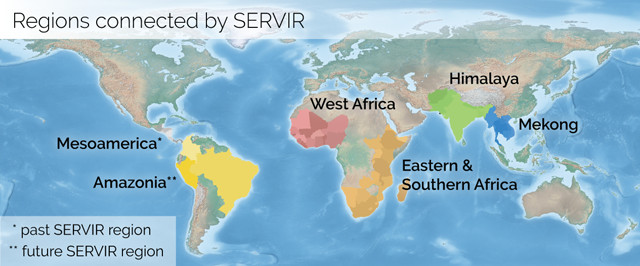

SERVIR (a Spanish word meaning “to serve”) puts geospatial satellite images and analysis tools into the hands of local decision-makers around the world. Established in 2005, the SERVIR program today has a presence in four locations across Africa and Asia. The goals of its Mekong hub are to build regional resilience to land and water resource pressures and to moderate the effects of climate change in this part of Southeast Asia.

Dan Irwin, a NASA research scientist, came up with the idea for SERVIR in 2003 during a meeting of Central American environmental ministers where representatives described the economic and climate challenges they faced. Irwin reasoned that access to a “big picture” could improve a lot of local decision-making. “NASA has an amazing constellation of satellites and it’s putting out a lot of fantastic data,” he says. “But how do you take [those data] and make them meaningful for users around the world, particularly in the developing countries, who don’t always have in situ data networks?”

Irwin also saw the potential in a USAID collaboration for such an enterprise. USAID is the lead U.S. government agency for foreign economic development, charged with addressing issues of global health, food security and environmental sustainability. NASA had plenty of technology resources to offer and USAID had the organizational and social ties to determine where those resources could best be put to use. Discussions between the agencies led to establishment of the SERVIR program in 2005.

In 2016, Thailand was in the midst of the second year of its worst drought in nearly 100 years. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/epixx.

SERVIR-Mesoamerica, the first SERVIR hub, was inaugurated in 2005 under the operating slogan “Connecting Space to Village.” It was headquartered in Panama City, Panama, where it supported community needs in Central America and the Dominican Republic through the Water Center for the Humid Tropics for Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC). Irwin supplied the new hub with geospatial imagery from NASA’s collection of Earth-observing satellites.

The SERVIR model proved popular. “We were doing some innovative work in Central America on land cover and water-quality management,” Irwin says, “and word got out. We started giving presentations at the Group on Earth Observations (GEO) and other venues, and the East Africa communities became interested in their own SERVIR hub.” SERVIR-Eastern and Southern Africa came into being in 2008 with headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya, to support the 20 member states of the Regional Center for Mapping of Resources for Development. SERVIR-Himalaya followed in 2010, operating from Kathmandu, Nepal, in support of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan. SERVIR-Mekong was launched in 2015; based in Bangkok, Thailand, it supports Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. The newest hub, SERVIR-West Africa, was inaugurated in 2016 and operates from Niamey, Niger, where it focuses primarily on the needs of Burkina Faso, Ghana, Niger and Senegal, as well as eight other countries.

Today, all science support for SERVIR is coordinated from an office at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., where Irwin is the program’s director.

Each hub receives support from USAID and NASA, although implementation and administration fall to a coordinating intergovernmental agency or NGO. The Mekong hub, for example, was put together as a consortium partnered with the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center (ADPC), an NGO responsible for programs that build community resilience to natural disasters, climate change and disease. The consortium was completed with partners from the Spatial Informatics Group (SIG), Deltares and the Stockholm Environment Institute. Together, its members provide a complementary mix of expertise in hydrology, geographic information system (GIS) design, remote sensing, risk analysis and program management. The hub is funded by the USAID Regional Development Mission for Asia, and works out of the ADPC headquarters in Bangkok.

The first SERVIR hub was inaugurated in 2005 in Panama. Since then, hubs have been opened in Africa, the Himalayas and Southeast Asia. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

The SERVIR-Mekong hub supports a region that is interconnected by geography and climate. The five countries of the Lower Mekong are home to almost 240 million people spread over just 1.9 million square kilometers — an area slightly smaller than Mexico but with almost twice its population. The impacts of development decisions almost always cross international borders, as NGOs have noted, so government and private policy planning must be done with an eye to conflicting agendas and shared environmental consequences.

The Mekong River and its tributaries provide irrigation and drinking water to the region and sustain its important fish populations. According to the National Heritage Institute (NHI), a U.S. NGO, the Mekong provides more food than any other river in the world. It’s also one of the world’s most threatened water systems.

The Mekong River and its tributaries, which yield more food than any other river in the world, provide irrigation and drinking water to the region and sustain its important fish populations. Credit: Thomas Schoch, CC BY-SA 3.0.

NHI data show that 48 major hydropower dams are either already operating or are under construction along the Mekong River, and another 71 are being planned. While dams can bring needed energy to communities, they can also have significant costs. Dams can alter access to water, disrupt the viability of fish populations, and reduce overall food security. Commercial harvesting of forest products and the infrastructure development that accompanies economic activity also threaten water quality across the region.

Climate change is placing additional pressures on the Lower Mekong, which is uniquely vulnerable to its effects. The Mekong River Commission, an intergovernmental water management organization, predicts that rising sea levels and more frequent precipitation will inevitably lead to more extreme weather and its associated impacts, such as floods, droughts, saltwater intrusion and soil erosion.

Under these circumstances, tools that help visualize and quantify local environmental conditions would almost certainly benefit the people charged with public planning.

The Sóơn La Dam on the Black River in Vietnam. Dams can alter access to water, disrupt the viability of fish populations and reduce overall food security. Credit: Tycho, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The regional nature of each SERVIR hub allows its staff to customize products to local problems and capabilities. “We really tried to start with the end users and develop products and services around them,” Irwin says.

Eco-Dash, for example, is a computer-based tool that scores changes in biomass quality across large geographic areas. It was developed by the SERVIR-Mekong team in response to a request from Winrock International, a U.S. NGO that administers the USAID-funded Vietnam Forests and Deltas (VFD) Program. The VFD Program is an effort to help the country develop climate-change resilience through such adaptation and mitigation approaches as sustainable landscapes and reduced emissions from deforestation.

To better illuminate how impacted ecosystems are evolving, Eco-Dash crunches multispectral imagery data from two Earth Observing System satellites and runs them through a standardized assessment algorithm — the Enhanced Vegetation Index — to generate a graphical depiction of changes.

Eco-Dash “provides consistent spatial and temporal comparisons of vegetation conditions over time,” says Tran Lan Huong, a Winrock GIS specialist. Like all SERVIR products, it’s available online at no cost, and is designed for ease of use: Set a few on-screen controls to define the search conditions, hit the “update” button, and wait about 15 seconds before results are drawn on a color-coded map. “We use it twice a year to assess the impact of our interventions in the forest areas of Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An provinces,” Huong says. “As these provinces are two of the largest forest areas in the country, the tool saves us both time and money.”

Another SERVIR-Mekong product, the Surface Water Mapping Tool (SWMT), was developed in response to a request from another NGO. NHI needed to make recommendations about optimal dam construction sites on the Xe Kong River, one of the Mekong’s large lower tributaries, as part of its support for the USAID Climate Resilient Mekong project. NHI asked for a tool to assess how proposed dams might impact the seasonal water cycles of the wetland environments that support fish spawning.

The SWMT processes archived imagery from Landsats 7 and 8 and draws maps depicting the extent of groundwater sources over selected time periods. Five government agencies and two NGOs in the region now use the tool for infrastructure planning.

The SERVIR-Mekong team tries to design its products for use with minimal information technology infrastructure. One solution they’ve embraced is cloud computing. “Like most of our work, the data at the core of [SWMT] are freely available to anyone,” says Ate Poortinga, an SIG hydrologist. “But SWMT requires a lot of data and a lot of processing power, so we took advantage of Google Earth Engine, which houses the entire imagery archive.”

Google Earth Engine allows users to work with large geospatial datasets on cloud servers. Nearly everything offered by the Mekong hub is now designed for, or is being converted for use with, Google Earth Engine. Hub staff members are still trained to teach outside users how to use SERVIR toolsets, however, to help users effectively interact with their geospatial data.

While government agencies, universities, NGOs and other organizations typically contact the hub staff directly for support, a “Request Technical Assistance” button on the landing page of the SERVIR-Mekong website offers everyone a fast and easy way to get help. “If a small NGO in the middle of Laos needed something, there’s a mechanism for engaging us even if they can’t physically travel to a SERVIR office,” says David Saah, director of the Geospatial Analysis Lab at the University of San Francisco and science and data co-lead at SERVIR-Mekong. Several tools, including Eco-Dash, began with a request via this button.

The path between request and completed product isn’t always straight. An NGO might need a tool for a remote area, but if official decisions are going to be made with it, a local government agency must still approve its use. The SERVIR-Mekong staff anticipates this by trying to involve all stakeholders throughout the entire development process.

“We invite all the representatives,” Saah says, “so we have pretty cross-cutting representation from government, academia and NGOs from each country. We bring them in for targeted workshops and we start to build a product together.” Along the way, members with expertise in areas such as policy, technology, science and employment each contribute to the final product.

This is a situation where the SERVIR-Mekong partnership with ADPC has paid off well, Saah notes; the extensive community and organizational networks built by ADPC throughout the Lower Mekong help identify stakeholders and engage them in SERVIR work. Such partnerships between hubs and regional agencies have been a key contribution to overall SERVIR program productivity.

Even with stakeholder collaboration, however, new projects can take a while to complete. “People exposed to new technologies, new tools and new opportunities can’t always articulate what they’re looking for,” says Peter Cutter, science and data co-lead at SERVIR-Mekong. “Sometimes we have to connect the dots of what we think they have in mind.” A rough concept like this will typically change the conversation and lead to something else, still provisional, but closer to the end goal. The process is repeated until stakeholders are comfortable with the product and its intended role in their domains.

Danny Hardin (left), a National Space Science Technology Center senior research scientist from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, trains three researchers from El Salvador to use SERVIR's products. Credit: SERVIR.

Just as NASA provides ongoing support to its space missions, it also provides ongoing support to its SERVIR hubs. The NASA SERVIR Coordination Office at Marshall Spaceflight Center is ready to help whenever a hub asks for assistance. Eric Anderson is the SERVIR-Mekong regional science lead. A research scientist at the University of Alabama in Huntsville and at the Marshall Spaceflight Center, Anderson works with the program through a cooperative agreement with the space agency.

Staying up to date is the first priority for the Science Coordination Office, Anderson says. “The hubs are well up to speed, but there’s always something new,” he says. “Part of my function is to participate in NASA applied science meetings, so our office is aware of the latest and greatest from any of those teams.”

During his term, Anderson says he has noticed that experiences reported back from SERVIR hubs are starting to influence NASA technical approaches. “Satellite developers are opening up more and more to hearing user community needs,” he says. “It’s nice to have information flow the other way — from on-the-ground users to scientists and engineers.”

USAID staff in each SERVIR region also coordinate with NASA to make sure the local hub’s needs are being met, and arrange for hub members to meet each year to exchange best practices. Irwin says that consistent USAID involvement has also influenced NASA operational practices. “NASA has learned a softer side from USAID as SERVIR has evolved,” he says. “How are country consultations developed? How do you ask the right questions and ask the right people? Once you have the needs, how do you develop and implement a process and gather metrics so you know that you’re doing a good job?” These are all questions NASA is now asking, he says. “That’s been valuable to NASA as we grow SERVIR and other programs.”

Additionally, informal networking across the hubs is now thriving on its own. Although each SERVIR hub has its own regional character, common issues and common solutions eventually tend to surface. “As the network has grown,” Irwin says, “the most exciting thing about SERVIR is the hubs working with each other. They exchange scientific ideas and algorithms. They even exchange their business and operational practices.” The hubs now maintain several inter-hub working groups to make sure that everyone is aware of what’s available and what works best, augmenting the support from the Science Coordination Office.

Passing autonomy to the hubs and to the communities they support is an implicit goal of the SERVIR program, Irwin says. “The vision is to work ourselves out of a job, or at least reduce our footprint as regions become self-sustaining.” Eventually, he says, the locals will “be the service providers and we’ll take more of a back seat role.” SERVIR-Mesoamerica, for example, ended its formal relationship with SERVIR in 2011. Years later, many of its original capabilities are still functioning through CATHALAC.

Work on new technologies continues throughout NASA and the space community. “There are new missions going on all the time that we have in our sights because they’re going to be game changers,” Cutter says. Right now, he’s specifically interested in a new NASA LIDAR satellite that will generate imagery that could improve forest models. He also notes that data sources outside of NASA, such as radar and multispectral imagery from European Space Agency Sentinel satellites, are being integrated into SERVIR tools.

The latest SERVIR-Mekong development project is the Regional Drought Information System. With the recent droughts still fresh in everyone’s memories, the Vietnam Academy for Water Resources (VAWR) has been charged with providing planning guidance to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development to mitigate future droughts. VAWR sought out SERVIR-Mekong for a solution. “Vietnam was under severe drought conditions … and there was a lack of information on the ground,” says Tran D. Trinh of VAWR. “We were looking for tools that could utilize remote sensing data for drought monitoring and management, and found that SERVIR-Mekong had the techniques and tools that we needed.”

SERVIR is currently active in more than 30 countries and is about to expand again; last year, NASA and the Peru office of USAID posted a grant opportunity for what will become SERVIR-Amazonia, a new hub for South America.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.