by Lucas Joel Tuesday, May 1, 2018

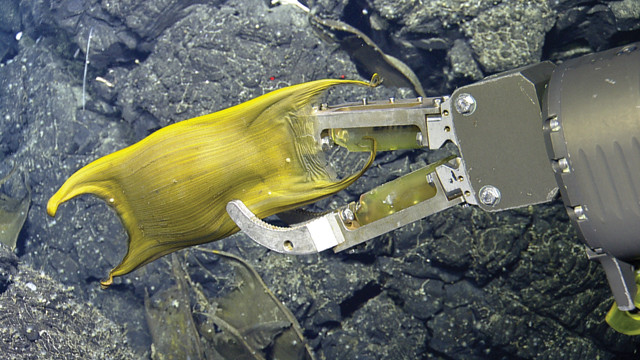

A skate egg case found near hydrothermal vents in the Galápagos spreading center. Credit: Ocean Exploration Trust.

In July 2016, a team of scientists came upon a surprise 1,660 meters beneath the ocean’s surface near the Galápagos Islands: a clutch of yellow eggs, laid by a Pacific white skate, a cousin of rays and sharks. It was not the eggs themselves that surprised the team, but where they were found: near a volcanic hydrothermal vent. The large number of eggs at the site led the team to suggest that the skate was likely using the vent’s heat to incubate the eggs.

The egg cases were discovered by researchers piloting Ocean Exploration Trust’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hercules while on a cruise to help Ecuador’s government define the borders of Galápagos National Park.

On a 15-hour dive to the Galápagos spreading center — a volcanic rift that divides the Cocos Plate to the north and the Nazca Plate to the south — Hercules “flew” through seafloor canyons and encountered a variety of sea life, such as alvinellid worms, which live in extremely hot waters like those next to hydrothermal vents, and bioluminescent shrimp glowing in the darkness. Then, with the scientists observing via video monitors on the surface ship, the eggs appeared near the ROV.

“No one was expecting to see these eggs,” says Brennan Phillips, an oceanographer at the University of Rhode Island (URI) and a co-author of a new Scientific Reports study describing the find. The discovery of egg cases purposefully laid next to a hydrothermal vent is a first.

Researchers found that water temperatures near the eggs were, on average, hotter than the surrounding waters. “The background temperature was about 2.76 degrees Celsius,” Phillips says. Some eggs were in waters of average temperature, but most were in warmer water, around 2.8 degrees Celsius, with the highest temperatures surrounding eggs being about 3.6 degrees Celsius. A temperature increase of only about 0.1 or 0.2 degrees Celsius is enough to decrease incubation times by months or even years, Phillips says.

Moreover, the fact that most of the 157 eggs the researchers counted were in relatively warm waters suggests the placement was intentional egg-laying behavior. “There seems to be some sort of optimal temperature that they were aiming for,” he says.

“We’ve never seen organisms using vents — because of their temperatures — as nurseries,” says Roxanne Beinart, a deep-sea biologist also at URI but who was not involved in the discovery. “That’s the new and exciting thing about this discovery,” Beinart says. So far, the behavior is unique among ocean animals, although some terrestrial animals — like some modern birds — are known to use geothermal heat to incubate their eggs, and some extinct sauropod dinosaurs are thought to have also displayed this behavior. Beinart adds that experiments on the relationship between temperature and the length of time it takes skate embryos to develop could help solidify the validity of the hydrothermal nursery hypothesis.

Phillips plans to investigate how other large marine species interact with submarine volcanic environments. For example, sharks — one of the longest-lived fish lineages, with origins extending back to the Paleozoic — may use rift environments to their advantage, he says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.