by Callan Bentley Monday, November 18, 2013

Copyright Callan Bentley, 2013

Copyright Callan Bentley, 2013

Editor's Note: Traditionally, EARTH has published a "highlights" or "year in review" issue at the end of the year. This year, we decided to try a new approach: We asked our staff and some frequent contributors to write a short commentary on something that grabbed their attention in 2013. We gave everyone carte blanche. What follows is a collection of extremely varied, often very personal insights into how the planet impacted each individual. You can find some online this month, but for the full grouping, you'll have to buy the issue here or subscribe.

We have just finished a year of tremendous scientific achievement. Human organs can be 3-D printed, exoplanets were spotted by the score, robot geologists roam the surface of Mars, and the cells of an extinct frog were brought back to life. We are living in a golden age of insight and technology. Science is changing our perceptions of the natural world and allowing us to do things of which our ancestors could only dream. As a means of sorting the real from the unreal, nothing beats science. Yet the science-deniers persist: It seems they just don’t like reality.

I gave a talk recently at a Road Scholars event, a learning experience intended to be intellectually stimulating for senior citizens. I spoke about the “Snowball Earth” hypothesis, an idea that ties together geology, chemistry, climate and the evolution of life into a single compelling story.

Afterward, one man asked what lessons the snowball episodes have to teach us about the current episode of climate change. I answered that it appears that the cold conditions of the snowballs were due to a global carbon dioxide drawdown, and that the current warming is clearly associated with a carbon dioxide buildup. When the carbon cycle gets perturbed, geophysics compels us to expect a change in the heat budget of the planet.

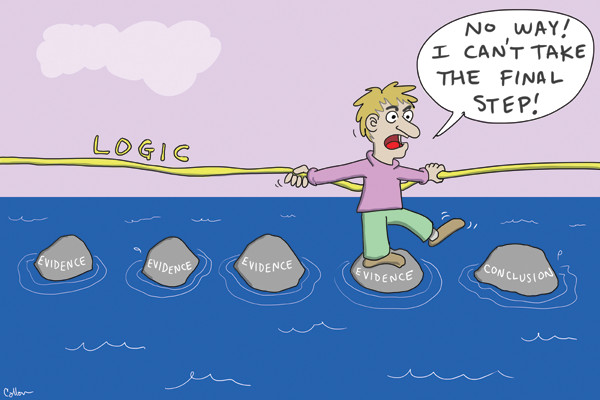

Among my audience were several vocal opponents of the notion that people have been responsible for much of this buildup. And although I spelled out the chain of evidence and asked them to pick out what they felt were the weak links, they were unwilling to accept the answer at the chain’s end. They had already embraced an alternate conclusion.

Another person asked about the origins of life. While science explains a few things about the self-organization of chemical components and the spontaneous rise of complexity, I told her, we still don’t know exactly how life began. Like the Snowball Earth, it’s an area of active research. Afterward, a second woman came up, dismayed by my answer. She wanted to quiz me about “how people could come from frogs.” Unsatisfied with my response, she asserted that the Bible was the inerrant word of God and evolution was invalid. She threw up her hands when I pointed out that from a scientific standpoint, biblical stories were in much the same class as Greek mythology or the oral traditions of the Australian Aboriginal dreamtime — ontological stories with no supporting evidence. Their ideas are not disproved by science, but they’re certainly extraneous to it. Disgusted, she dismissed me by saying, “I’ll be praying for you!”

At the college where I teach, I also routinely encounter students who hold nonscientific worldviews. Those who believe evolution to be false are also quite likely to dismiss humanity’s role in changing the global climate, which is part of the reason that the National Center for Science Education, which previously focused mainly on fighting anti-evolution movements, has now also turned its attention to climate change deniers. In both cases, the lack of empirical validation is seen as irrelevant; the conclusion is the cherished thing.

In a recent class, I contrasted catastrophism with uniformitarianism, and noted how science had repeatedly shown religious claims to be untrue: an Earth-centered universe, a global flood, a young Earth, for example. Afterward, a student remained: “I guess it just comes down to faith,” she said. “There’s a reason they call it faith.” In other words, the conclusion is sacrosanct; logic be damned.

Could there be a less compelling argument? Should juries convict people for murder if the prosecuting attorneys said they have faith that the accused were guilty?

Often in our culture, science is rendered disposable if it stomps on a cherished claim; faith trumps reality. This attitude is internally inconsistent: Atomic theory is OK when we use it to X-ray our teeth or build a nuclear power station, but invalid when it comes to assessing the age of the planet. Evolutionary insight is OK when it guides the production of our annual flu shot, but deniers refuse to let it tell them from whence they came. Science is the way forward, but not for people who don’t want to go forward.

This year, science has given us new, more precise temperature reconstructions that show unprecedented warming in the past 150 years, and fossils of the oldest-known ape, evidence that confirms molecular estimates of our ancestors’ evolutionary split from monkeys about 25 million years ago. The more science examines climate change or evolution, the more solid each idea becomes. Our origins and the repercussions of our acts are important issues. Humanity asks, “What are we doing here? And what are we going to do about it?” Science can aid us in answering these questions — but will we let it?

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.