by Thea Boodhoo Tuesday, February 7, 2017

Articulated dinosaur fossils can still be found at the Flaming Cliffs, and frequently are — by tourists, guides, locals and poachers. Mongolian law instructs those who find such specimens to notify the area's single ranger, but no signage or leaflets exist to convey this. Even when a fossil is reported, Bayanzag Park has no resident paleontologist to excavate it, no prep lab to clean it, no collections facility to store it and no museum to display it. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

The bones were too yellow, too translucent, and the skeleton had no hands. I could tell the skeleton wasn’t a dinosaur, but the illusion was enough to bring my brain to a momentary halt.

“He made this out of camel bones,” said Aza, my guide at Bayanzag Park in the Mongolian Gobi, home of the Flaming Cliffs where Velociraptor was first discovered. The artist behind the camel-bone creation, Munkhbaatar, had a genuine love of dinosaurs but no scientific training.

“There are some fossils in the other room,” Aza noted. We stepped into a dusty alcove where most of a vertebral column, complete with ribs and as long as a loveseat, lay across a low shelf, still in its red-orange sandstone matrix. It was likely from the Nemegt Formation, known for dinosaurs. It belonged in a museum collection, but this small, unofficial building was the closest thing the park had to one.

I was there as a representative of the Institute for the Study of Mongolian Dinosaurs (ISMD) to assess the status of fossils in the park and meet with locals to plan informational material. Ever-present in the back of my mind was the need for a museum in the park, with community outreach programs, a lab and collections facilities.

I had met the ISMD’s founder, Bolortsetseg Minjin, the previous summer, a world away from the Flaming Cliffs. I had spent that summer at Dinosaur National Monument in Utah working on an interactive quarry map. One morning, I heard that some Mongolian VIPs were visiting. One of them was Bolortsetseg (who, like most Mongolians, seldom uses her last name), a paleontologist I had read about who played a key role in bringing a poached Tarbosaurus skeleton home to Mongolia. She agreed to an interview for the blog I wrote that summer and told me about the challenges facing Mongolian paleontology. We talked about her ongoing science outreach work with Mongolian youth and her dream of a permanent museum at the Flaming Cliffs. Bayanzag Park is one of the most popular tourist spots in Mongolia, and the cliffs are considered by many paleontologists to be paleontological holy ground. Her visit to Dinosaur was, in part, research for a future Bayanzag museum.

Replica fossils, including teeth, tail spikes and a Triceratops horn, get young Mongolians excited about paleontology. Paleontologist Bolortsetseg Minjin hopes to inspire some of the children to pursue careers in paleontology and all of them to see poaching as an activity that robs their country of its fossil heritage. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

The next time we met, six months later, was over noodles at a Korean restaurant in Manhattan. This time, she interviewed me — about creating a website for the Flaming Cliffs. Our discussion continued over weekly cross-country calls (I live in San Francisco; she in New York City) and evolved into a crowdfunding campaign, a suite of outreach materials, a social media presence and a lot of IRS paperwork. I became an officer and director of the ISMD when we registered as a U.S. nonprofit in July, and by September I was in the Gobi Desert, at a place most paleontologists only dream of visiting, standing next to a dead camel mounted to look like a theropod.

Since 2009, Bolortsetseg has brought fossil replicas to workshops like this one in Arvaikheer. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

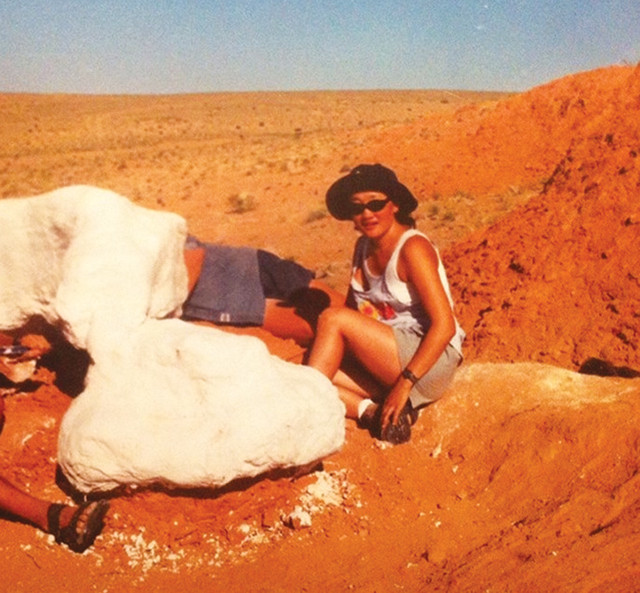

Bolortsetseg joined the first American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) expeditions to the Mongolian Gobi after her country emerged from Soviet influence. In this 1997 image, she is jacketing a Khaan mckennai specimen at the Ukhaa Tolgod site. Credit: Bolortsetseg Minjin.

Bolortsetseg was born in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital city. Her mother taught at a local college and her father, Minjin Chuluun, was a respected invertebrate paleontologist. In 1996, Professor Minjin was invited on an expedition led by paleontologists Mike Novacek and Mark Norell of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York. With some effort, Bolortsetseg’s father convinced the Mongolian crew to enlist her as a cook. Her master’s in paleontology hadn’t exactly prepared her for carving mutton and frying dumplings, so she spent her days prospecting, bringing in delicate mammal and lizard fossils for which she had a keen eye. This earned her the wrath of the Mongolian team leaders, who swore she would never be invited back into the field with them. But she also earned the respect and support of Novacek and Norell, who invited her to complete a doctorate through a joint program of City University of New York and AMNH.

“She left Mongolia that year for the first time, barely speaking English and not knowing a soul in New York aside from the paleontologists she worked with.

AMNH left a deep impression on Bolortsetseg the first time she entered the building. Mongolia had a handful of museums at the time, but nothing compared to even the entrance hall at AMNH. And behind the scenes were vast fossil collections, labs and highly skilled professionals who deftly handled, prepared, shipped and mounted fossils of all sizes. She says she realized quickly how much work would have to be done before her own country — whose fossils were this museum’s bread and butter — would be ready to do its dinosaurs justice. That work became her mission.

The Flaming Cliffs are the first place dinosaur fossils were discovered in Mongolia, by AMNH expeditions during the 1920s. Today, the cliffs and their fossils are legally protected as part of Bayanzag Park, but enforcement of that protection is underfunded and facilities for fossil storage and preparation are nonexistent. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

The history of paleontological science in Mongolia began in 1922, when AMNH sent zoologist Roy Chapman Andrews on the third of the Central Asiatic Expeditions. Andrews led a team of paleontologists, geologists and archaeologists into the Gobi Desert. It was here, at a red sandstone outcrop, that Andrews named the Flaming Cliffs, where they found their first Mongolian dinosaur: Protoceratops.

Few Mongolians know that Velociraptor was first discovered in their country, in part because each fossil excavated has been taken elsewhere for display. Credit: illustration by Emily Willoughby, courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Mongolian Dinosaurs.

AMNH pulled out of Mongolia in 1925 as Soviet influence took hold, but that didn’t mark the end of exploration in the country. In the late 1940s, a Soviet expedition discovered the giant tyrannosaur Tarbosaurus bataar. In the 1960s, paleobiologist Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska led the Polish-Mongolian Expeditions, discovering the enigmatic Deinocheirus and the famed “fighting dinosaurs” specimen of a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in mortal combat. Once the Cold War ended, AMNH quickly returned, and they’ve been sending expeditions almost every summer since.

Today, the Flaming Cliffs is known worldwide among fossil enthusiasts. The Cretaceous-aged red sandstone matrix preserves stark white fossils in three dimensions, often fully articulated. The “Jurassic Park” film franchise added to the site’s fame in 1994 when it chose the name of a certain small, feathered Flaming Cliffs theropod for its human-sized, scaly antagonists. Today, Velociraptor mongoliensis is one of the most well-known dinosaurs, everywhere except Mongolia.

Like many fossils from Mongolia, this Protoceratops is fully articulated and preserved by sandstone in three dimensions, making it a highly sought-after specimen. Also, like many fossils from Mongolia, it was exported from Mongolia illegally for sale to a private collector in the United States. Credit: Bolortsetseg Minjin.

When Bolortsetseg first visited Mongolia after moving to New York, she started talking to kids about dinosaurs. Most had never seen a dinosaur fossil. None could name a species from Mongolia. Some even told her dinosaurs were mythological.

Roy Chapman Andrews may have begun a prestigious tradition of dinosaur paleontology in Mongolia, but his expeditions also heralded a less noble legacy: removing fossils from the country. When Andrews published his riveting tales of scientific discovery, Mongolia’s fossil riches caught the attention of collectors from around the world and a black market trade was born. Mongolians desperate under Soviet influence, and later during the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, were more than happy to extract old animal bones for money to feed their families.

Today, Mongolian laws prohibit the export of vertebrate fossils and require excavators to carry permits, but those laws have been hard to enforce without funding or manpower. In the last four years, Bolortsetseg has helped repatriate more than 30 illegally exported Mongolian dinosaurs that have turned up in the U.S. alone. Preventing Poaching With Education and Infrastructure

It may look like a child's toy collection, but these models are a core component of each Institute for the Study of Mongolian Dinosaurs (ISMD) workshop kit. In one activity, the plesiosaurs, smilodons and crocodilians are used to differentiate dinosaurs taxonomically from other animals that are often mistakenly called dinosaurs. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

“The realization that so many fossils had been stolen over the past century inspired Bolortsetseg to take action. “Once a fossil left the country,” she says, “knowledge left with it.”

Fossil poachers often leave behind a mess. Skulls are prized because they catch the highest price and are easier to ship, while less valuable bones are broken in the rush to complete unpermitted excavation. Scraps like these are left in haphazard piles. Credit: Bolortsetseg Minjin.

“The workshops have been a hit with kids and teachers almost every summer since, but a box of replicas and a PowerPoint presentation can only go so far. Back in New York, Bolortsetseg focuses much of her time on bringing real dinosaurs back to Mongolia. Seeing the skeletons in person, she says, will have a much bigger impact.

Bolortsetseg says she hopes that bringing dinosaurs back to Mongolia will help future Mongolians summon the names of Velociraptor, Protoceratops and Oviraptor as easily as the average American conjures Triceratops, T. rex and Stegosaurus. A host of benefits should come with the infrastructure envisioned to make this dream real: increased tourism, local science literacy, a conservation mentality and economic opportunities. With locally relevant programs and a conscientious fee structure, fossil parks and museums have the power to improve the well-being of rural communities by serving as gathering places that foster conversation and inspire new ways of thinking. Eventually, by helping Mongolians see dinosaurs as more valuable when they stay in the country, Bolortsetseg hopes to prevent incidents like what happened in 2012.

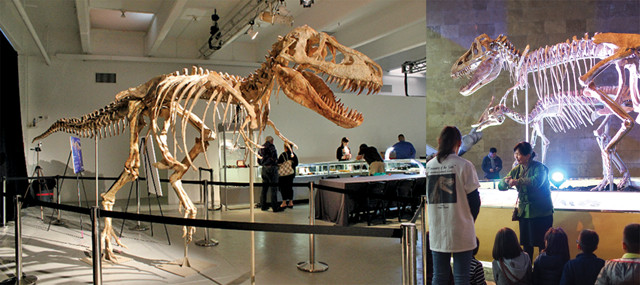

In 2012, an illegally exported Mongolian Tarbosaurus skeleton went up for auction in New York. Bolortsetseg lives in New York, and rallied authorities to have the skeleton sent back to Mongolia instead of to a private collection. She took this photo (below) of the fossil while it was still on display at the auction house. Today, the same skeleton (right) resides at the new Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia's capital city. Credit: below: Bolortsetseg Minjin; right: Thea Boodhoo.

“A giant short-armed, two-fingered predatory dinosaur from Asia of 70 million years ago,” is how University of Maryland paleontologist Thomas Holtz described Tarbosaurus bataar. I’d challenged him to do so without mentioning T. rex, the standard to which most people compare large theropods. Since 2012, however, Tarbosaurus has become the most famous dinosaur in Mongolia.

The success of the Tarbosaurus repatriation marked a new phase for the ISMD. The story had been followed closely in Mongolia, and suddenly kids in her workshops already knew the name of a dinosaur before she got there. Fossils became a hot issue in national politics, and reporters from around the world wanted to know Bolortsetseg’s life story. Poaching by native Mongolians, too, was on the rise as word spread even further that dinosaurs were worth money to collectors. Both knowledge and fossils were now in demand, and Bolortsetseg needed more resources. She needed a museum, and the ISMD’s vision of a permanent structure at the Flaming Cliffs was no closer to launching than it had been in 2007. There was, however, one museum within reach.

As part of the dinosaur workshops, children are given an assignment to find the Mongolian dinosaurs on display in the Moveable Museum. The treasure hunt drives home what the Americans who built the museum already know: Mongolians have a lot to be proud of when it comes to paleontology. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

In the 1990s, AMNH owned several Moveable Museums that traveled around New York City, bringing the Mesozoic to public schools; then it ran out of funding. In 2013, AMNH donated one of these museums to the ISMD — a giant blue Winnebago with the image of a near-life-size sauropod on the side, under the English words, “Dinosaurs: Ancient Fossils, New Discoveries.”

Gerry Ohrstrom, an investor and philanthropist who has known Bolortsetseg for years, funded transport of the Moveable Museum from New York to Ulaanbaatar. The bus first toured its new home in August 2015, roving all the way to the Flaming Cliffs thanks, in part, to an Indiegogo campaign that raised $4,460 from 61 backers. The crowdfunded resources weren’t quite enough to bring the museum down the long dirt road to the Flaming Cliffs and back, but Bolortsetseg made up the difference from her own savings.

To the grade-schoolers in rural Mongolian towns, many of whom live in yurts and know the back of a horse better than the back of a school bus, the arrival of the Moveable Museum brings the same reaction as a spaceship landing. It’s huge: too tall for Mongolian garages and too long to maneuver in most parking lots, so it usually stops in the street, blocking traffic for added effect. As the hatch opens, mechanized stairs lower themselves to the feet of the first kid in line and conditioned air whooshes out as if from an airlock. Inside, artifacts of strange worlds greet them: Protoceratops skulls and Oviraptor nests, images of Earth 100 million years ago, and glowing interactive panels in a language most of the kids can’t read. The lights inside are halogen — expensive-feeling and serene compared to the flickering fluorescents ubiquitous in Mongolian classrooms. The exhibits are modern, made of acrylic and steel, with no trace of the Soviet-era cinder blocks or exposed electrical wiring common to most Mongolian museums.

Tarbosaurus quickly became the most famous dinosaur in Mongolia after the repatriation of a poached skeleton made world news in 2012. By 2016, if there was one Mongolian dinosaur that any workshop student already knew of, it was Tarbosaurus. The species name, bataar, means "hero" in Mongolian. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

“Many of the dinosaurs on the Moveable Museum are replicas of specimens of Mongolian dinosaurs that AMNH visitors have enjoyed since Roy Chapman Andrews shipped them out of the Gobi generations ago. The children of Arvaikheer and Bayankhongor who climbed into our old blue Winnebago, however, were the first of their lineage ever to see them.

Most ISMD workshops are held in classrooms, like this one in Bayankhongor. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

Four Weeks in Mongolia

In summer 2016, ISMD applied for nonprofit status in the U.S. and launched a fundraising campaign to keep the Moveable Museum running, create new outreach and educational materials, and hold four weeks of workshops for kids aged 7 to 14 in Bayankhongor, Arvaikheer, Dalanzadgad, Mandalgovi and Ulaanbaatar. By August 14, the campaign had raised its goal of $45,000, and around midnight on September 1, Bolortsetseg and I landed at Chinggis Khaan International Airport.

“We assembled a team and gathered supplies. Mongolia is a big country with few paved roads, so we would spend more days traveling than educating. Workshops were booked in school classrooms, government buildings and libraries. We had to get as much work in as we could by the end of September, when temperatures would drop fast and the Moveable Museum would need to be stored for winter. The ISMD’s plan for its most ambitious workshop season was in place.

A new dinosaur park in the Gobi Desert city of Dalanzadgad is already inspiring a generation. Scientifically accurate information on the park's dinosaurs is, as yet, nonexistent. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

We started every workshop with an activity called “Minii Dinozavr,” meaning “My Dinosaur.” While “minii” is a Mongolian word, “Dinozavr” (pronounced dee-no-zow-er) is the Russian interpretation of the Latin word, familiar to Westerners, that means “terrible lizard.” Dinozavr is not a common word in Mongolia, but Bolortsetseg prefers it to the Mongolian word for dinosaur, “uleg gurvel.”

Although most kids in our workshops weren’t familiar with dinosaurs at all — in fact, we even met adults who weren’t sure dinosaurs were real — there were exceptions. In Arvaikheer, one boy brought in his favorite comic, starring a Tarbosaurus, and an entire class in Mandalgovi already knew that birds were dinosaurs. In another workshop, a group of 11- to 13-year-olds spontaneously started Mongolia’s first junior paleontology club, which they named Velociraptor. Most of the time, the level of existing knowledge in a town depended on whether Bolortsetseg had previously held workshops there. But the kids who were most familiar with dinosaurs were in the city closest to the Flaming Cliffs, Dalanzadgad, where a brand new dinosaur-themed amusement park — yet to be named — had just opened (see sidebar).

Scientifically accurate information on dinosaurs, written in Mongolian, is hard to find, but creativity abounds. This dinosaur sculpture was crafted from camel bones by a local artist at Bayanzag Park. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

At Dalanzadgad, the team split. Two stayed behind to run workshops while I and three others drove to Bayanzag. This was where we met the artist named Munkhbaatar and his camel-bone dinosaur. Our main destination, however, was the Flaming Cliffs.

Visitors can drive to the highest point atop the Flaming Cliffs. There, a small row of vendors sell handcrafted souvenirs to tourists, and a few unmarked trails lead down into the sandstone maze below. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

At the top of the Flaming Cliffs, a dry wind tossed sand in my eyes as I squinted toward the impossibly empty horizon. It was beautiful, but for a state park it was too empty. There were visitors, but just as in the theme park in Dalanzadgad, there was a surprising lack of information for them. No signs, no park maps, no trail markers. As I explored, I visualized the possibilities. A plaque by a small tree-shrub might read, “Zag (Haloxylon ammodendron): This small tree only grows in sandy, dry climates.” Or on a paper handout, one might see, “Gobi racerunner (Eremias przewalskii): Look for this cold-blooded lizard warming itself on the sandstone.” At the end of a trail that was unmarked, I imagined a sign describing the vast Gobi landscape below. “Desert of Dinosaurs: Eighty million years ago, this landscape was covered in red-orange sand dunes. Standing here then, you might spot a Velociraptor stalking a Protoceratops, or a young Oviraptor couple helping their first hatchling out of its shell.”

Collections and lab facilities are badly needed at important Mongolian fossil sites like the Flaming Cliffs, where camp owners are likely to have a few fossils stashed away for curious customers. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

“Aza and I climbed down from the cliffs and drove to several other areas within Bayanzag Park. At three stops, Aza showed us unexcavated fossils discovered on prior tours. We had no tools, time or permit to excavate them, but also no way to guarantee they would still be there the following year. Even if we could excavate them, the closest fossil prep lab was more than a day’s drive away in Ulaanbaatar. The need for a museum with a lab and collections facility here in the park was undeniable. At our last stop, I spent half an hour casually prospecting and found bone fragments every few steps. How many pieces had left Mongolia in the pockets of tourists who honestly didn’t know they were breaking the law because there were no signs, no flyers, not even a notice at the airport to inform them?

At the new Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs in Ulaanbaatar, poached dinosaur fossils that have been repatriated are finding a home. Information is provided for visitors in both Mongolian and English. Credit: Thea Boodhoo.

Our last full day in Mongolia was spent at the Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs (CMMD) in Ulaanbaatar, a new museum established as a home for the famous Tarbosaurus skeleton and other repatriated fossils. Bolortsetseg and the museum director signed a Memorandum of Understanding regarding future collaboration between the ISMD and CMMD. We discussed sharing funding for fossil preparation and specimen storage, joint fieldwork in the coming year, ongoing educational programs, and a future museum at Bayanzag.

The CMMD is a good start for making dinosaurs accessible in Mongolia, even though much of the facility is still inaccessible to the public, save an entrance hall where attendants in handmade, green felt dinosaur vests sell tickets and remind visitors not to take photos unless they have paid an extra fee. In the entrance hall, a pair of fully assembled giant skeletons greet visitors from atop a rocky platform, ribs and skulls lit from below by color-changing lights. On the left is Saurolophus, a Mongolian hadrosaur with a gentle, duck-like face. On the right is the Tarbosaurus. Surrounding them along the walls are the remains of Protoceratops, Oviraptor, and more. All repatriated after illegal export, they were once cloistered away from science and the public. Now they are on display for all, with informational plaques in English and Mongolian.

Bolortsetseg says she’s often approached by journalists and documentarians seeking dramatic tales of poacher-thwarting justice. They’re always disappointed. Bolortsetseg doesn’t see poachers as enemies, no matter how infuriating it can be to find the shattered remains of a dinosaur that has been pried from the rock for profit. Financial desperation, she says, is what drives poaching, and that can be fought by improving the economy. Tourism is already Mongolia’s second-biggest industry, and dinosaurs are one thing almost every tourist asks about. That’s something that can be capitalized on, but not if fossils keep leaving the country. Poachers, in the long term, are hurting themselves, Bolortsetseg says.

She also says that poaching is best fought with education. Once-a-year workshops and a Moveable Museum are just the beginning. With permanent museums at important fossil sites like the Flaming Cliffs, Bolortsetseg says she hopes to inspire children to become scientists, convert tourists into supporters and show those who would sell a dinosaur for profit that the biggest gains come from keeping dinosaurs at home, next to a gift shop.

Plans are in the works for a museum at the Flaming Cliffs. In the long term, we hope the museum will serve as a testing ground and a template for facilities serving each of Mongolia’s important fossil locales. Thanks to Bolortsetseg’s repatriation and poaching prevention work, there will likely be plenty of dinosaur fossils to fill them. And, if the enthusiasm of our young workshop participants is any indication, we may even have enough Mongolian paleontologists to staff them.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.