by Erik Sturkell, Axel Sjöqvist, Lennart Björklund and Andreas Johnsson Monday, May 4, 2015

Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

When geologists gather for a beer after work or around a campfire after a long day in the field, the conversation sometimes turns to how our profession is portrayed on film. Are geologists heroes or villains? Do they appear only in supporting roles — their parts limited to entering an office, uttering “Drill here,” and promptly leaving the scene — or are they main characters?

Michael Easton of the Ontario Geological Survey and colleagues addressed some of these points in a 1990 article, “Hollywood’s Portrayal of Geologists: Earth Scientists on Celluloid,” in the pages of this magazine, then called Geotimes. The writers concluded that geologists are usually pictured as “good guys” — and they are most often guys — who work outdoors and love to seek out the local bar for a beer (or two).

This stands in stark contrast to the customary film portrayals of physicists and chemists. In a 1988 study, “The Physicist as Mad Scientist,” science historian Spencer Weart, now retired from the American Institute of Physics, found that physicists and chemists are very often described as mad scientists striving for world domination or the total destruction of Earth. Even in cases where they were not portrayed as wholly evil, Weart found they were still often depicted as absent-minded or misunderstood geniuses.

Much has changed in the last few decades, however, so we decided to reexamine the question of how geologists are portrayed on film, incorporating movies released since 1990.

Credit: AGI.

Credit: AGI.

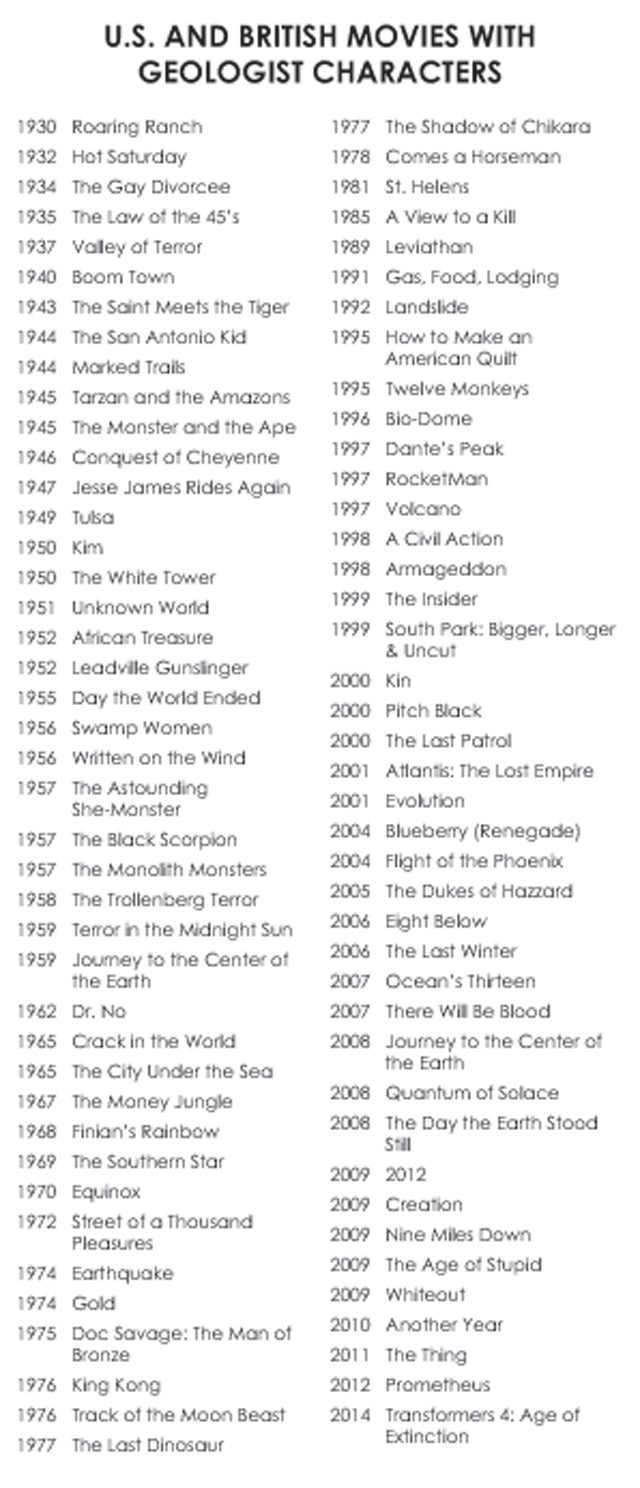

On the Web, there are many references to geology movies, but, to our knowledge, there is no complete list of “geologist movies,” so we set out to create one. Our quest started with movies from our home country, Sweden. To no one’s surprise, however, we soon found that only a handful existed. So, we decided to expand our search to include American and British movies, limiting our scope to those that have been shown on the silver screen, and excluding (for now) made-for-television and direct-to-DVD movies, for which less data are available. Still, we couldn’t resist giving some examples of these productions (listed above). While sporting some geologically bizarre titles, this list also includes our favorite made-for-television movie, “Supervolcano,” which aired in 2005 and featured more than five heroic geologists.

Our data collection was based on movies seen by us or our acquaintances. We then expanded it by collecting material from websites such as the Internet Movie Database, or IMDb (http://www.imdb.com), Turner Classic Movies (http://www.tcm.com) and American Movie Classics Filmsite (http://www.filmsite.org). The database Subzin (http://www.subzin.com) was useful for searching how often the word “geologist” occurs in movie dialogue.

However, the simple uttering of the word “geologist” in the film does not necessarily make it a “geologist movie.” We define that as a movie with a clearly identified geologist in the cast, either in a main or supporting role. Our minimum criterion was that at least one geologist — dead or alive — must appear on screen. An example of a movie failing this criterion is the 1968 film “Tarzan and the Jungle Boy,” in which a reporter and his girlfriend search for a feral boy, the son of a drowned geologist whose body is never found, nor seen on screen.

Although some movies feature other types of geoscientists, such as geophysicists, seismologists and paleontologists — the 1976 movie “King Kong,” for example, includes both a geologist and a paleontologist — for the purposes of this study, we did not include these in the general category of geologists because they are usually portrayed on film performing distinctly different tasks. Geologists are typically identified as working directly on rocks, whereas geophysicists are often shown doing seismic interpretation, for example, and paleontologists are shown digging for bones with little mention of the geology involved. We did observe, however, that although scientists in these fields appeared less frequently on film than geologists, they were usually portrayed in a positive light.

Our database now comprises 83 movies, featuring 131 movie geologists — enough to allow us to draw some interesting conclusions.

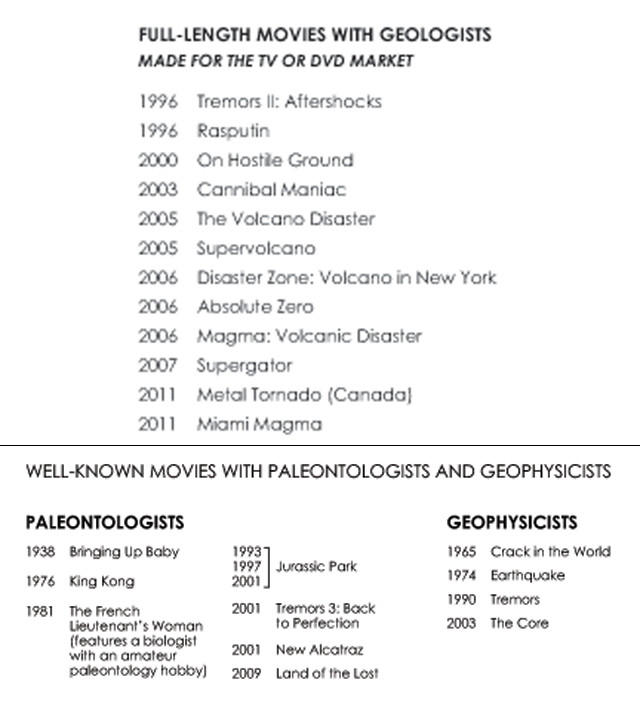

he roles, genders, moral characters and survival rates of movie geologists. The smaller bar charts further discriminate geologists' survival rates according to their moral characters. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI, remade from Sturkell, Sjöqvist, Björklund, and Johnsson.

The majority of geologists appear in supporting roles. Only about a third of geologists play leading roles. Most movies feature only one geologist. However, 29 films feature more than one, and 12 movies include more than two geologists. The 1997 movie “Dante’s Peak” boasts the highest number of geologists, with a grand total of seven (see sidebar).

The vast majority of movie geologists are male. Science certainly faces gender inequality issues, but our analysis reveals that, when i" comes to scientists, Hollywood seems to have an even greater lack of gender diversity. Just 14 female geologists appear in 12 movies, accounting for only 11 percent of movie geologists. This compares unfavorably to the 32-percent female membership rate of the Geological Society of America (GSA) and to the 20-percent female membership rate of the American Geophysical Union.

Minority scientists are even less well represented on the big screen. The only example we could find was the 2009 sci-fi disaster film “2012,” in which British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor portrays Adrian Helmsley, a geologist who discovers and warns the world that neutrinos from a massive solar flare are heating Earth’s core and will destroy the planet.

Left: In "The Lost World: Jurassic Park," Julianne Moore plays Sarah Harding, a behavioral paleontologist. Credit: ©Universal Studios/Amblin Entertainment via Movie Stills Database; The 2009 sci-fi disaster thriller "2012" features one of the rare portrayals of a minority geologist, played by actor Chiwetel Ejiofor. Credit: ©Sony Pictures/Columbia Pictures via Movie Stills Database.

We also analyzed the types of films in which movie geologists appear by tallying genre tags in IMDb. Many films are tagged with more than one type of genre, but we learned that 47 movies out of 83 fall into the category of action, adventure or Westerns. Twenty-seven movies are classified as dramas, many of which are also romantic. Twenty-four are horror or thrillers and 19 are sci-fi. Apparently, movie geologists do not typically sing and dance or go to war, as we found only two musicals and one war movie. Interestingly, there were also two animated movies featuring geologists: “South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut,” released in 1999, and “Atlantis: The Lost Empire,” released in 2001.

Left: In the 1938 screwball comedy "Bringing Up Baby," Cary Grant plays a paleontologist trying to find a missing brontosaurus bone and secure a donation for his museum from a wealthy matriarch whose niece is played by Katherine Hepburn. Credit: ©RKO Radio Pictures via Movie Stills Database. Right: In the 1985 James Bond film, "A View to a Kill," Tanya Roberts plays a geologist who helps foil an evil industrialist's plot to destroy Silicon Valley by triggering a megaquake on California's San Andreas and Hayward faults. Credit: ©Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/United Artists via Movie Stills Database.

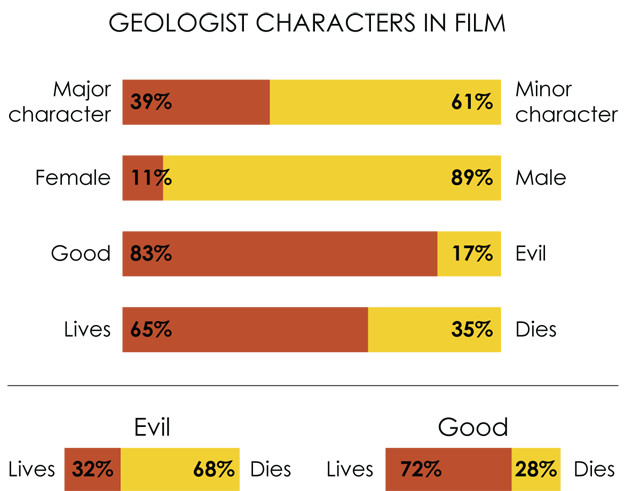

In the 1957 movie "Monolith Monsters," alien crystals grow to gigantic proportions when exposed to water and become animated, rampaging monsters. Credit: Wikipedia, public domain.

Unsurprisingly, the roles of movie geologists have changed along with the public perception of what geologists do, and with the changing tastes of movie audiences.

The first movie with a geologist in the cast, in a supporting role, was the 1930 Western “Roaring Ranch.” The first movie in which a geologist had a leading role was the 1932 film “Hot Saturday,” in which Randolph Scott plays the geologist Bill Fadden, who lives in a cave. He loses his girlfriend to the character Romer Sheffield, played by Cary Grant. But, then again, who could compete with Cary Grant?

Geologists popped up in supporting roles in many Western movies during the 30s and 40s. The 1944 film “Marked Trails,” for example, features an oil-prospecting geologist who is described by the “bad guys” as “walking around and taking notes all over the place” and setting fire to gas seeps. (This was indeed an early inexpensive technique for identifying untapped near-surface reservoirs.) He is an innocent good guy, but is murdered while plotting his maps.

The production of geologist movies increased in the mid-1940s, and the genres became more differentiated. In addition to Westerns, we start to see adventure films, thrillers, disasters and monster movies featuring geologists. In 1957, two monster-themed geologist movies appeared, “The Black Scorpion” and “The Monolith Monsters,” both featuring geologists in heroic main roles.

The Cold War era put its stamp on geologist movies as well with the emergence of a now-familiar theme — the threat of world domination posed by an evil organization. The first James Bond movie, “Dr. No,” arrived in 1962 in the midst of the Cold War, and featured a murderous geologist as part of an evil uranium-mining criminal syndicate.

The first female geologist appeared in a Cold War-era film, “Crack in the World,” a 1965 disaster movie in which all three main characters are geologists. In the process of drilling for geothermal energy, they detonate a nuclear bomb at the crust-mantle boundary, causing a global fissure that threatens to destroy the world. The detonation of another nuclear bomb is, of course, required to halt the propagating crack, and one of the geologists heroically sacrifices himself to do it.

One of the few other female geologists is featured in the second Bond movie to have a geologist, 1985’s “A View to a Kill.” As in “Dr. No,” geology is involved in the villain’s plot to achieve world domination, this time of the economic variety. The diabolical scheme entails triggering massive earthquakes simultaneously on the San Andreas and Hayward faults to destroy Silicon Valley — and the computer-microchip manufacturers that populate it. The movie features two geologists, one who dies horribly while helping the villain, and one, the California State Geologist and “Bond girl” portrayed by actress Tanya Roberts, who survives.

These Cold War-era films gave way to the disaster movies of the 90s. Examples are “Dante’s Peak” and “Volcano,” which both appeared in 1997 and together feature a total of nine geologists, several in main roles. “Armageddon” followed the next year, featuring two geologists as part of a team of oil-drillers-turned-astronauts who must divert an asteroid on a collision course with Earth.

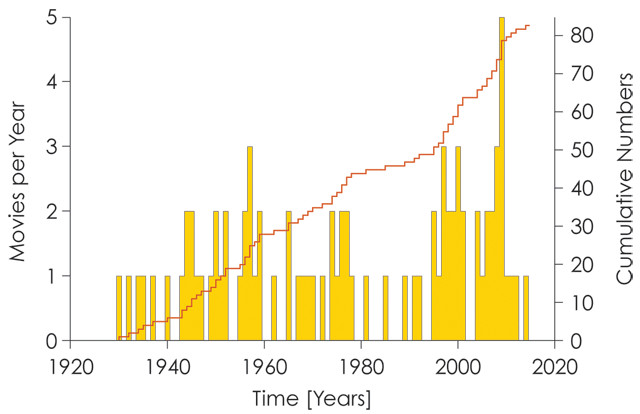

In our data set, we see two pulses of disaster movies involving geologists, one in the years before the turn of the century and the second in recent years, with an all-time high in 2009.

The rate of production of geologist movies over the years. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI, remade from Sturkell, Sjöqvist, Björklund, and Johnsson.

We found a wide range of moral qualities in movie geologists. Most of the 131 movie geologists — 83 percent, in fact — are go"d people by conventional standards. Some even go on to rescue the world, as in “Crack in the World,” “2012” and “Armageddon.”

We classified movie geologists as “evil” if they did things like attempt to steal property, deceive by misrepresenting geology, or kill people to achieve their goals. Very few of the movie geologists are entirely evil, driven by their own machinations. More commonly, the evil geologist is the corrupted aide of the main villain. In the earliest geologist movies, the evil geologist is commonly a petroleum prospector working for a malicious and greedy businessman who schemes to oust, by any and all means, a local landowner.

Of the 131 geologists, we identified 22 geologists exhibiting various shades of evil (17 percent). In addition, there are 13 “false geologists,” characters posing as geologists. These fall into two groups. The larger one comprises nine villains posing as geologists for criminal or espionage purposes; five of these characters die. The smaller group comprises four good people, often police or FBI agents working undercover, none of whom die.

In 2007's "There Will Be Blood," Daniel Day-Lewis plays a driven and opportunistic oilman. Credit: ©Miramax Films/Paramount Vantage via Movie Stills Database.

The most evil geologist we have identified — an envoy of the devil posing as a female scientist — a"pears in the 2009 horror movie “Nine Miles Down.” In the plot, 25 members of a research crew mysteriously vanish while attempting to drill an ultra-deep borehole in the middle of the Sahara. The security guard investigating the case encounters an unblemished, scantily clad woman, happily jogging in the hot desert sun and claiming she is a surviving scientist. The guard begins to experience sudden and frequent blood-drenched nightmares while the mysterious woman exhibits increasingly strange behavior. The guard concludes that the project drilled so deep that it breached hell, releasing an evil “something” that is responsible for the deaths of the missing researchers.

Only two of the “true” geologists, or 1.5 percent, are completely malevolent. Among them, we count Daniel Plainview, played by Daniel Day-Lewis in an Oscar-winning role in 2007’s “There Will Be Blood.” Plainview begins his career employed by the Kansas Geological Survey, but a tragic moral decline follows. (We surmise no causal connection.) The movie begins in a mineshaft where Plainview mines silver. He later goes into the oil business and starts buying up local ranches. As a businessman, his character becomes increasingly unsympathetic. The richer he gets, the greedier, meaner, more paranoid and cynical he becomes — traits that come to a head in a grand finale of murder and utter self-destruction.

The other example of an evil geologist is Professor Dent, who appears in the 1962 James Bond movie “Dr. No.” Dent is part of Dr. No’s evil crime syndicate, misleading society by falsifying geologic records and acting as Dr. No’s hit man. Dent shoots and kills two people to cover up his crimes, but is eventually done in by Bond. Such deeds clearly qualify him as an evil movie geologist, and would also constitute a serious breach of the GSA code of conduct.

Left: In the 1959 movie "Journey to the Center of the Earth," James Mason portrayed Professor Lindenbrook and Pat Boone played a geology student who together descend into Earth through the Icelandic volcano Snæfellsjökull. Credit: ©20th Century Fox via Movie Stills Database; Right: In "Ocean's Thirteen," Brad Pitt portrays "Rusty" Ryan, a con man who briefly masquerades as a geologist to place a camera, disguised as a seismometer, inside a casino that he and his associates are planning to rob. Credit: ©Warner Bros. via Movie Stills Database.

We also found some movie geologists whose conduct was highly questionable and fell into a moral gray area. In 1959’s “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” based on Jules Verne’s 1864 novel of the same name, Professor Lindenbrook consults the world’s leading petrologist — who, much to our delight, is named Professor Goetaborg and hails from Stockholm. (Goetaborg is a misspelling of the second-largest town in Sweden, but then again we may take comfort in the fact that all the Icelandic words are also consistently misspelled.) After receiving no response to his letter, Lindenbrook realizes that Goetaborg is busy stealing his idea and organizing a separate expedition to Iceland.

While this qualifies Goetaborg as a rival colleague with deplorable professional ethics, in our estimation, he is not downright evil, and he is also made to pay for his crimes. Goetaborg is later found murdered in his hotel room, after which, his widow, Madame Goetaborg, becomes aware of his misdeeds and donates his equipment to, and joins, Lindenbrook’s expedition party.

Steve Buscemi portrayed a mentally unstable geologist nicknamed Rockhound in the 1998 movie "Armageddon." Credit: ©Touchstone Pictures via Movie Stills Database.

In the 2012 film "Prometheus," a geologist played by actor Sean Harris meets a grisly end after being assimilated by aliens. Credit: ©20th Century Fox via Movie Stills Database.

Four movies feature geologists gone mad, though only in one movie, 1998’s “Armageddon,” is the geologist, nicknamed Rockhound, loony (or eccentric, take your pick) from the start. He later loses his marbles entirely during the team’s mission on the surface of the asteroid. It should be noted, however, that Rockhound has two doctorates, one in geology and one in chemistry. Given Weart’s earlier findings about the madness of movie physicists and chemists, perhaps the latter qualifications explain Rockhound’s mental state.

In the 2012 sci-fi movie “Prometheus,” a geologist lacking some basic social skills is infected by an alien and dies. The moral: Do not pat aliens on the head, even if they look innocent. In the 1976 film “Track of the Moon Beast,” an equally bizarre fate befalls a geologist who is hit by a meteorite, which turns him both insane and evil. He commits suicide to save the world, when he realizes that the meteorite fragments are turning him into an evil killing lizard during each full moon.

In the 1970 movie “Equinox,” the geologist character goes crazy after a heroic battle with Satan and his demons. Our conclusion, therefore, is that only one out of 131 geologists is inherently crazy (in movies). The other three go mad from work-related, but quite exotic, causes.

The worst slaughter of geologists occurs in 1967’s “The Money Jungle,” in which a consortium of five oil companies bids on parcels off the coast of Santa Barbara, Calif., holding an estimated 3 billion barrels of oil. Four geologists representing four different oil companies are murdered in innovative ways: One is electrocuted while charging his golf cart, one is poisoned, one is gassed and one dies when his model train explodes. The deaths cast suspicion on the fifth company, although that company’s geologist is also subsequently killed. The detective investigating the case finds that the drill cores have been switched in a ruse to imply that the offshore parcels are barren, and that the only people who knew the truth were the murdered geologists. It turns out the murders were instigated by the CEO and the ex-wife of a competitor as part of an elaborate plan to unravel the consortium.

We are concerned about the high overall fatality rate of movie geologists. Of the 131 geologists, 46 (35 percent) are killed in action. Of those killed, most (25) are murdered — some in unusual ways, like assimilation by aliens. The rest are killed in work-related accidents involving volcanic bombs, meteorites, falls into open holes and chasms, or drowning in lahars. However, we also find a strong correlation between characters’ ethical standards and their likelihood of death, with evil geologists dying at twice the rate of the good guys.

Both the animated movie and television show "South Park" feature a geologist, Randy Marsh, who works at the South Park Center for Seismic Activity. Credit: ©Comedy Central.

Our study of 84 years of movie geologists bolsters our initial hypothesis that geologists, movie and otherwise, are essentially good people, who sometimes even perform heroic deeds. Movie geologists usually survive, especially if they only play supporting roles. Compared to the real world, however, a disproportionate number of movie geologists are male. The female geologists who do appear are overwhelmingly good characters; none of the female true geologists are evil. Five of the female geologists die (36 percent), exhibiting a death rate similar to their male colleagues’ rate of 35 percent. So, at least in death there is gender equality.

Thus, with a steady 83 percent of movie geologists being good guys, we dare conclude that the entertainment industry views geology as an"upstanding profession, albeit one with an appallingly high death rate.

The actress Finn Carter portrayed seismology student Rhonda LeBeck in the 1990 movie "Tremors." Credit: ©Universal Studios via Movie Stills Database.

The portrayals and fates of movie geologists have changed over time, in tune with perceived real-world threats, societal needs and geopolitics. This holds true from early oil and mineral prospecting themes, through wartime monsters and Cold War-era criminal organizations, and to the present-day crop of disaster movies. This suggests that the positive public perception of geologists, as mirrored in 84 years of movies, could potentially change, if real-life geologists were caught using their professional knowledge in destructive acts against society.

The rising trend of movies featuring geologists also parallels the public’s increasing awareness of our dependence on natural resources and of threats from environmental changes and natural disasters, which will continue to require real-world geologic expertise. We thus predict that the future of cinema will also hold more heroic movie geologists, with or without beer, occurring in dramatic situations both on and off Earth.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.