by Mary Caperton Morton Friday, November 9, 2018

Locations of highlighted glaciers of the Rockies. Credit: K. Cantner, AGI.

Glaciers are one of the most powerful erosive agents on Earth, capable of pulverizing entire mountain ranges into dust. These rivers of ice grind over high-elevation landscapes, leaving behind striking pyramidal peaks, knife-edge arêtes, classic U-shaped valleys, deep bowl-shaped cirques and rocky moraines. Glaciers advance and retreat — and thicken and thin — as the balance shifts between snow accumulation and ice melt. But, according to the World Glacier Monitoring Service, the recent global trend has been toward more melting, meaning that glaciers on all seven continents have been receding.

On the ground, it’s hard to fathom the effects that glaciers once had on the now nearly ice-free Rocky Mountains, but from the air, the landscape is clearly haunted by the ghosts of glaciers past. When Glacier National Park in northwestern Montana was established in 1910, the 4,000-square-kilometer park boasted roughly 150 named glaciers. By 2015, only about 25 icefields remained that were large enough to still be classified as glaciers. The same story repeats throughout the Rockies, where once-dominant glaciers have been reduced to scattered pockets of rapidly thinning ice. Today, 62 named glaciers remain in Montana; 38 remain in Wyoming; and 14 remain in Colorado.

In 2015, pilot and photographer Garrett Fisher set out in his antique 1949 Piper Cub aircraft to photograph all the remaining glaciers in the American Rockies — from Glacier National Park to the Wind River Range in Wyoming to the Colorado Rockies. “The project was born partially out of a personal desire to see the glaciers, and then it grew with a sense of urgency as I realized how fast the glaciers are melting,” Fisher says.

Over two months, Fisher flew over 108 glaciers — and scraps of ice that used to be classified as glaciers — in the Rocky Mountains. His images, published in his 2018 book, “Glaciers of the Rockies,” showcase the last glints of glacial ice, as well as freshly revealed scars from thousands of years of erosion — features that will remain long after the last drops of glacial meltwater drain down the Continental Divide. The following photos offer a north-to-south selection of the glacial and postglacial features Fisher has documented in the American Rockies.

Glacier National Park, Montana

The American Rockies straddle North America's Continental Divide: Snow and rain that fall to the east of the divide eventually drain into the Atlantic Ocean via the Gulf of Mexico, while precipitation to the west finds its way to the Pacific Ocean. Water from Two Ocean Glacier, which sits on the north slope of Vulture Peak (top image, left foreground), once emptied into both the Pacific and the Atlantic — a hydrologically rare feat — but now the remaining patches only drain to the east of the divide. Two Ocean is one of a handful of glaciers that can be seen from the comfort of a car along Glacier National Park's famous Going to the Sun Road, west of Logan's Pass. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

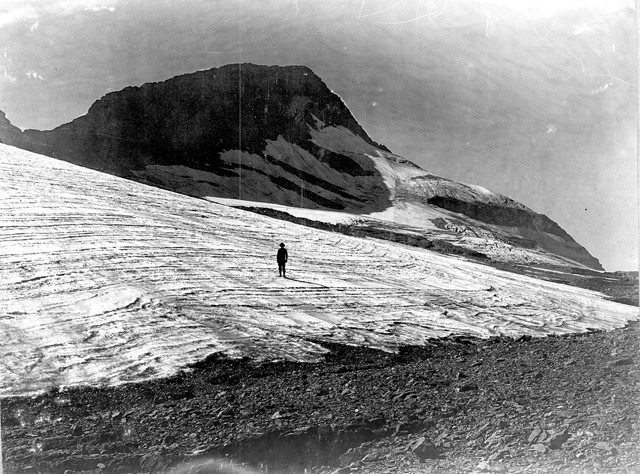

The toe of Two Ocean Glacier in front of Vulture Peak, seen in 1913. Credit: M.R. Campbell/USGS archives.

The American Rockies straddle North America’s Continental Divide: Snow and rain that fall to the east of the divide eventually drain into the Atlantic Ocean via the Gulf of Mexico, while precipitation to the west finds its way to the Pacific Ocean. Water from Two Ocean Glacier, which sits on the north slope of Vulture Peak (top image, left foreground), once emptied into both the Pacific and the Atlantic — a hydrologically rare feat — but now the remaining patches only drain to the east of the divide. Two Ocean is one of a handful of glaciers that can be seen from the comfort of a car along Glacier National Park’s famous Going to the Sun Road, west of Logan’s Pass. At right, the toe of Two Ocean Glacier is seen in front of Vulture Peak in 1913.

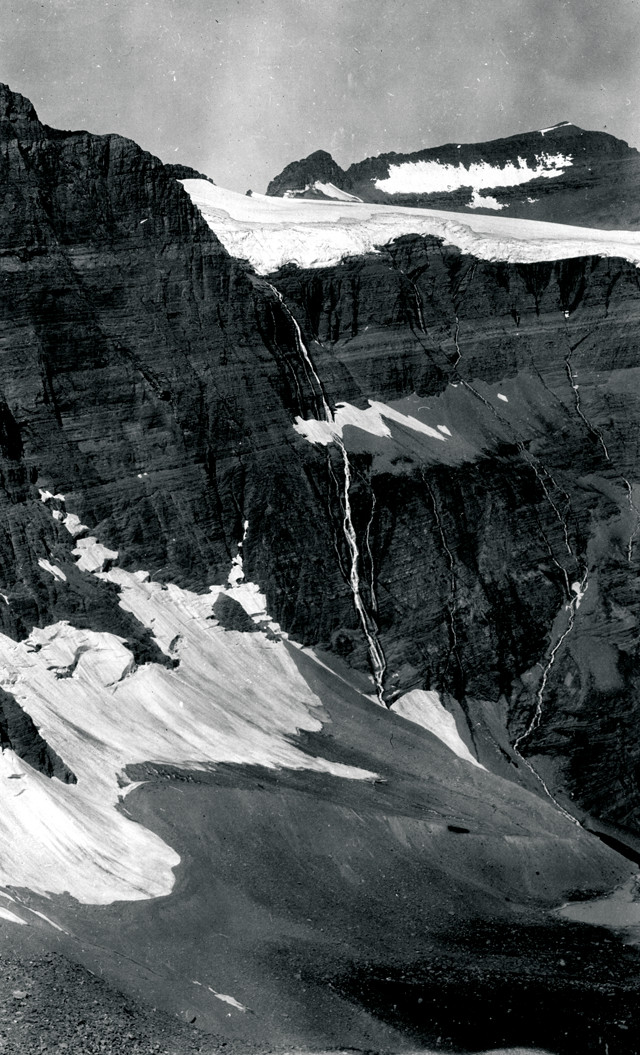

In 2009, the once-sprawling Shepherd Glacier was downgraded to a glacieret, a remnant ice patch that shows little or no movement. By definition, an active glacier must be larger than 0.10 square kilometers, which is the minimum size for an ice patch to be heavy enough to move downhill under its own weight. A U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) image captured in 1913 shows Shepherd at its former size. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

The depressions where two meltwater lakes exist in the 2015 aerial photo were entombed under ice in 1913. Credit: W.C. Alden/USGS archives.

In 2009, the once-sprawling Shepherd Glacier was downgraded to a glacieret, a remnant ice patch that shows little or no movement. By definition, an active glacier must be larger than 0.10 square kilometers, which is the minimum size for an ice patch to be heavy enough to move downhill under its own weight. A U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) image captured in 1913 (right) shows Shepherd at its former size. The depressions where two meltwater lakes exist in the 2015 aerial photo were entombed under ice in 1913.

Old Sun Glacier, on the eastern flanks of Mount Merritt, is a rare exception to the trend of rapid ice loss in Glacier National Park: Since 1960, Old Sun has lost only about 14 percent of its area, a comparatively slow demise. Old Sun's longevity is attributed to its high-elevation accumulation zone, above 2,600 meters, where seasonal snow piles up each winter and compacts into denser firn ice, which eventually adds to the bulk of the glacier. As seen in this aerial photo, deep crevasses appear on the glacier's surface, resulting from the shear stress of ice moving downhill. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

In 1939, Old Sun covered a similar area, but today the glacier's thickness and volume has decreased. Credit: USGS archives.

Old Sun Glacier, on the eastern flanks of Mount Merritt, is a rare exception to the trend of rapid ice loss in Glacier National Park: Since 1960, Old Sun has lost only about 14 percent of its area, a comparatively slow demise. Old Sun’s longevity is attributed to its high-elevation accumulation zone, above 2,600 meters, where seasonal snow piles up each winter and compacts into denser firn ice, which eventually adds to the bulk of the glacier. As seen in this aerial photo, deep crevasses appear on the glacier’s surface, resulting from the shear stress of ice moving downhill. In 1939 (right), Old Sun covered a similar area, but today the glacier’s thickness and volume has decreased.

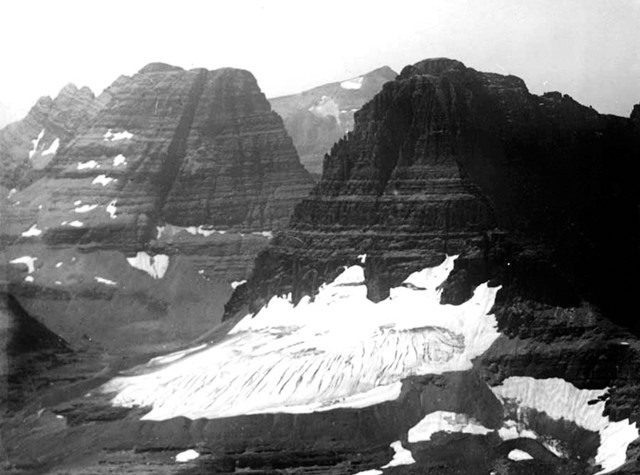

Ahern Glacier is perched on a ridge between Ipasha Peak and Ahern Peak, east of the Continental Divide. Ahern Glacier Falls, which free falls more than 500 meters on its way to Helen Lake, is visible in this aerial photo (below left). The falls can also be seen in a 1911 USGS photo (below right), which shows Ahern Glacier with Ipasha Peak in the background.

Ahern Glacier is perched on a ridge between Ipasha Peak and Ahern Peak, east of the Continental Divide. Ahern Glacier Falls, which free falls more than 500 meters on its way to Helen Lake, is visible in this aerial photo. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

The falls can also be seen in this 1911 USGS photo, which shows Ahern Glacier (aerial) with Ipasha Peak in the background. Credit: W.C. Alden/USGS archives

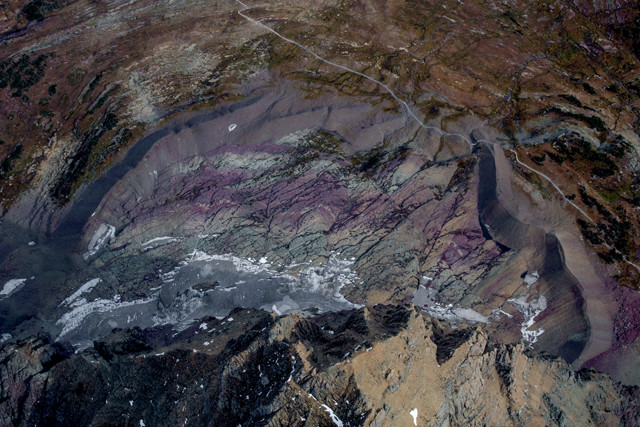

Clements Glacier on Mount Clements, which towers above the Logan Pass Visitor Center on Going to the Sun Road, is one of the most accessible glacial features in the park. A popular hiking trail, visible at upper right in this bird's-eye photo, leads visitors past the few remaining scraps of Clements on the way to Hidden Lakes. This photo also shows how ice polishes bedrock and leaves steep piles of debris called moraines that mark the glacier's ghostly outline. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

Clements Glacier as seen from the ground in 1914. Credit: Morton Elrod/USGS archives.

Clements Glacier on Mount Clements, which towers above the Logan Pass Visitor Center on Going to the Sun Road, is one of the most accessible glacial features in the park. A popular hiking trail, visible at upper right in this bird’s-eye photo, leads visitors past the few remaining scraps of Clements on the way to Hidden Lakes. This photo also shows how ice polishes bedrock and leaves steep piles of debris called moraines that mark the glacier’s ghostly outline. At right, Clements Glacier is seen from the ground in 1914.

Located just outside Glacier National Park to the southwest, Grant Glacier is one of 20 glaciers being documented in the USGS' ongoing Repeat Photography Project. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

Located just outside Glacier National Park to the southwest, Grant Glacier is one of 20 glaciers being documented in the USGS’ ongoing Repeat Photography Project. Originally photographed in 1902 (below), Grant Glacier has been photographed every summer since 1997 in an effort to document annual changes to the park’s glaciers. Photographs are taken in late summer, after the winter snows have melted and exposed the remaining ice, and from the same vantage point as the early 1900s images.

Originally photographed in 1902, Grant Glacier has been photographed every summer since 1997 in an effort to document annual changes to the park's glaciers. Photographs are taken in late summer, after the winter snows have melted and exposed the remaining ice, and from the same vantage point as the early 1900s images. Credit: Morton Elrod/USGS archives.

This tongue of rock on the northeast side of Crazy Peak in the Crazy Mountains is all that remains of the dozens of glaciers that once decorated this curiously named mountain range in southwestern Montana. Rock glaciers form when surface ice melts, leaving a layer of talus covering an underlying mixture of ice and rock. The buried ice continues moving downhill, creating rippled lobe patterns in the talus at the surface. Rock glaciers — some still active, with buried ice continuing to flow, others dried to the roots — can be found throughout the Rocky Mountains. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

This tongue of rock on the northeast side of Crazy Peak in the Crazy Mountains is all that remains of the dozens of glaciers that once decorated this curiously named mountain range in southwestern Montana. Rock glaciers form when surface ice melts, leaving a layer of talus covering an underlying mixture of ice and rock. The buried ice continues moving downhill, creating rippled lobe patterns in the talus at the surface. Rock glaciers — some still active, with buried ice continuing to flow, others dried to the roots — can be found throughout the Rocky Mountains.

Grasshopper Glacier once stretched several kilometers along a ridge in Montana's Beartooth Mountains, but now is reduced to several smaller glaciers, each tucked into a different north-facing cirque. The glacier was named for the millions of Rocky Mountain locusts that were entombed in the ice when a swarm encountered a blizzard hundreds of years ago. Dating exactly when these insects died is difficult, but the species — Melanoplus spretus — went extinct roughly 120 years ago and it's thought that these particular insects died between 200 and 400 years ago. The locusts entombed in ice used to be a much more prominent feature of the glacier and were once a tourist attraction, reachable on horseback or foot, just northeast of Yellowstone National Park. But seasonal melting and rapid decomposition of the exposed insects has made them a rare find today. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

Grasshopper Glacier once stretched several kilometers along a ridge in Montana’s Beartooth Mountains, but now is reduced to several smaller glaciers, each tucked into a different north-facing cirque. The glacier was named for the millions of Rocky Mountain locusts that were entombed in the ice when a swarm encountered a blizzard hundreds of years ago. Dating exactly when these insects died is difficult, but the species — Melanoplus spretus — went extinct roughly 120 years ago and it’s thought that these particular insects died between 200 and 400 years ago. The locusts entombed in ice used to be a much more prominent feature of the glacier and were once a tourist attraction, reachable on horseback or foot, just northeast of Yellowstone National Park. But seasonal melting and rapid decomposition of the exposed insects has made them a rare find today.

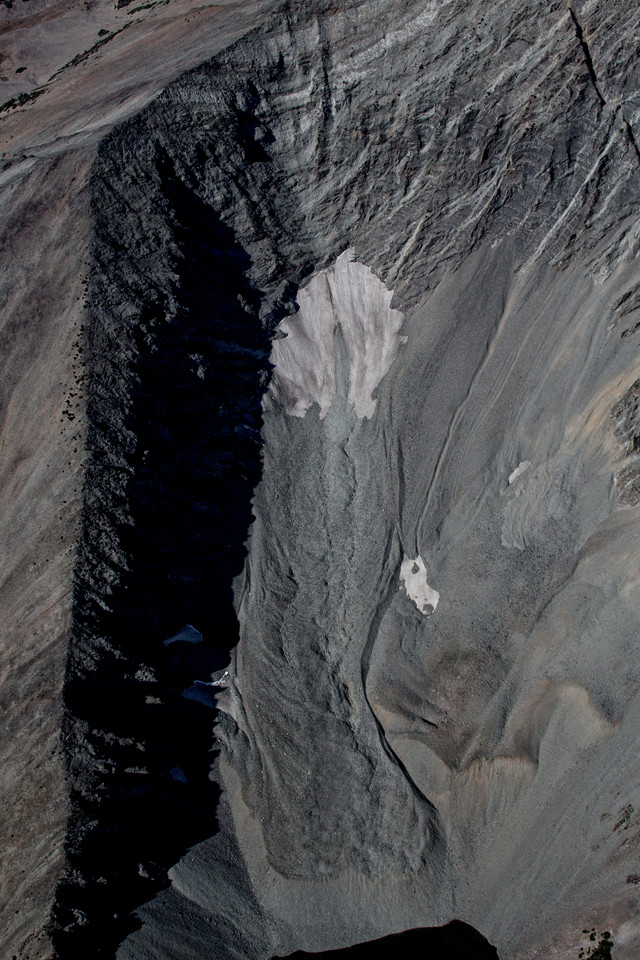

At 4,015 meters, Cloud Peak is the highest point in north-central Wyoming's Bighorn Mountains. On the northeastern side of the peak is a massive bowl-shaped cirque that holds what is left of the only remaining glacier in the range. Cirques represent the highest reaches of glaciers, where snow and ice accumulate and compact to form glacial ice. This ice usually spills out of one side of the bowl and flows downhill, creating a river of ice down the flank of a mountain. Cloud Peak Glacier was first photographed in 1905, when roughly 14 million cubic meters of ice filled much of the cirque. In 2010, the glacier's volume was about 2 million cubic meters. If this rate of melting continues, Cloud Peak Glacier is projected to disappear between 2020 and 2034. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

At 4,015 meters, Cloud Peak is the highest point in north-central Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains. On the northeastern side of the peak is a massive bowl-shaped cirque that holds what is left of the only remaining glacier in the range. Cirques represent the highest reaches of glaciers, where snow and ice accumulate and compact to form glacial ice. This ice usually spills out of one side of the bowl and flows downhill, creating a river of ice down the flank of a mountain. Cloud Peak Glacier was first photographed in 1905, when roughly 14 million cubic meters of ice filled much of the cirque. In 2010, the glacier’s volume was about 2 million cubic meters. If this rate of melting continues, Cloud Peak Glacier is projected to disappear between 2020 and 2034.

Schoolroom Glacier, seen here with Grand Teton (left) and Middle Teton (right) towering in the distance, presents textbook examples of glacial features, including the lateral and terminal moraines that flank a brilliant turquoise tarn, visible in this aerial photo. Moraines are created as moving glaciers push rocks and debris toward the edges of the ice; these features can be used to trace the past extent of a glacier. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

Schoolroom Glacier, seen here with Grand Teton (left) and Middle Teton (right) towering in the distance, presents textbook examples of glacial features, including the lateral and terminal moraines that flank a brilliant turquoise tarn, visible in this aerial photo. Moraines are created as moving glaciers push rocks and debris toward the edges of the ice; these features can be used to trace the past extent of a glacier.

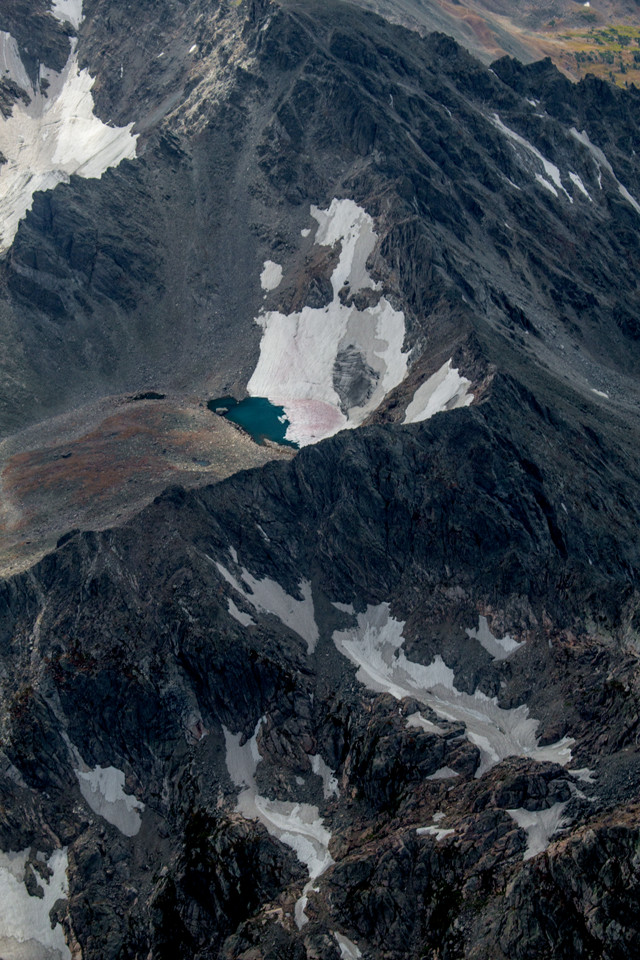

East of the Tetons, the Wind River Range runs 160 kilometers along the Continental Divide through west-central Wyoming. Each winter, more than 500 centimeters of snow fall on the "Winds," helping feed the largest expanse of surviving glaciers in the Rocky Mountains. In total, ice in the Wind River Range covers nearly 56 square kilometers — more than all the remaining glacial ice in Glacier National Park. Most glaciers in the Winds — such as the Fremont, Sacajawea and Helen glaciers (pictured here from left to right: Fremont at upper left, Sacagawea above the lake, Helen in the foreground) — face north or east and are thus protected from the afternoon sun. The pyramid-shaped peak of Mount Helen (sharp peak at upper right) is typical of glacier-carved summits. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

East of the Tetons, the Wind River Range runs 160 kilometers along the Continental Divide through west-central Wyoming. Each winter, more than 500 centimeters of snow fall on the “Winds,” helping feed the largest expanse of surviving glaciers in the Rocky Mountains. In total, ice in the Wind River Range covers nearly 56 square kilometers — more than all the remaining glacial ice in Glacier National Park. Most glaciers in the Winds — such as the Fremont, Sacajawea and Helen glaciers (pictured here from left to right: Fremont at upper left, Sacagawea above the lake, Helen in the foreground) — face north or east and are thus protected from the afternoon sun. The pyramid-shaped peak of Mount Helen (sharp peak at upper right) is typical of glacier-carved summits.

Covering about 2.8 square kilometers, Gannett Glacier — the largest glacier in the American Rockies — is a fitting cloak for Gannett Peak (the snowcapped peak at upper left), the highest mountain in Wyoming at 4,210 meters. Despite its impressive size and remote, high-altitude location in the heart of the Wind River Range, however, Gannett is losing ice at an alarming rate. It has shrunk in area by about 40 percent since 1950, when it covered about 4.6 square kilometers; and in the quarter-century between 1958 and 1983 alone, it is estimated to have thinned by 18.6 meters. Meltwater from Gannett Glacier empties into Dinwoody Creek, which finds its way into the Wind River and then into the Yellowstone River. So, while Gannett Peak may be one of the most remote summits in the Lower 48, water from its glacier flows across a vast stretch of Wyoming and Montana. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

Covering about 2.8 square kilometers, Gannett Glacier — the largest glacier in the American Rockies — is a fitting cloak for Gannett Peak (the snowcapped peak at upper left), the highest mountain in Wyoming at 4,210 meters. Despite its impressive size and remote, high-altitude location in the heart of the Wind River Range, however, Gannett is losing ice at an alarming rate. It has shrunk in area by about 40 percent since 1950, when it covered about 4.6 square kilometers; and in the quarter-century between 1958 and 1983 alone, it is estimated to have thinned by 18.6 meters. Meltwater from Gannett Glacier empties into Dinwoody Creek, which finds its way into the Wind River and then into the Yellowstone River. So, while Gannett Peak may be one of the most remote summits in the Lower 48, water from its glacier flows across a vast stretch of Wyoming and Montana.

During the last glacial maximum, between 26,000 and 13,300 years ago, the Colorado Rockies were buried under ice caps hundreds of meters thick, with a crowning ice cap sitting over what is now Rocky Mountain National Park. Today, only 14 named glaciers remain across Colorado. The largest — and southernmost — is Arapaho Glacier, tucked on the northeast-facing slopes between North and South Arapaho peaks, about 30 kilometers due west of Boulder. Arapaho Glacier is a key water source for the Boulder metro area's population of about 300,000. Although hikers can still view the glacier from the Arapaho Glacier Trail, the ice itself has been closed to visitors since a cholera outbreak in the 1920s that was linked to the glacier's watershed. This glacier has shrunk to less than half its size since the early 1900s and is projected to disappear by 2075. Credit: Garrett Fisher.

During the last glacial maximum, between 26,000 and 13,300 years ago, the Colorado Rockies were buried under ice caps hundreds of meters thick, with a crowning ice cap sitting over what is now Rocky Mountain National Park. Today, only 14 named glaciers remain across Colorado. The largest — and southernmost — is Arapaho Glacier (center of image), tucked on the northeast-facing slopes between North and South Arapaho peaks, about 30 kilometers due west of Boulder. Arapaho Glacier is a key water source for the Boulder metro area’s population of about 300,000. Although hikers can still view the glacier from the Arapaho Glacier Trail, the ice itself has been closed to visitors since a cholera outbreak in the 1920s that was linked to the glacier’s watershed. This glacier has shrunk to less than half its size since the early 1900s and is projected to disappear by 2075.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.