by Timothy Oleson Monday, May 16, 2016

Kevin Williams (left) and Trevor Jennings conduct a ground-penetrating radar survey at a cemetery in western New York. Credit: courtesy of Kevin Williams.

Grass-covered and mostly free of tombstones or other markers, several plots at Oakwood Cemetery in Niagara Falls and Holy Mother of the Rosary Cemetery in Cheektowaga, just outside of Buffalo, appeared on the surface to be devoid of burials. The cemeteries were interested in whether the plots could be used for future interments, but first wanted to confirm that the ground below wasn’t already occupied — ideally without digging to check.

“With a lot of cemeteries, they could just go back into their records and see if there were burials there,” says Kevin Williams, a geologist at Buffalo State. But both Oakwood and Holy Mother of the Rosary “had lost their records in the early 1900s. So … they weren’t sure if [the grassy plots] were actually empty or not,” he says.

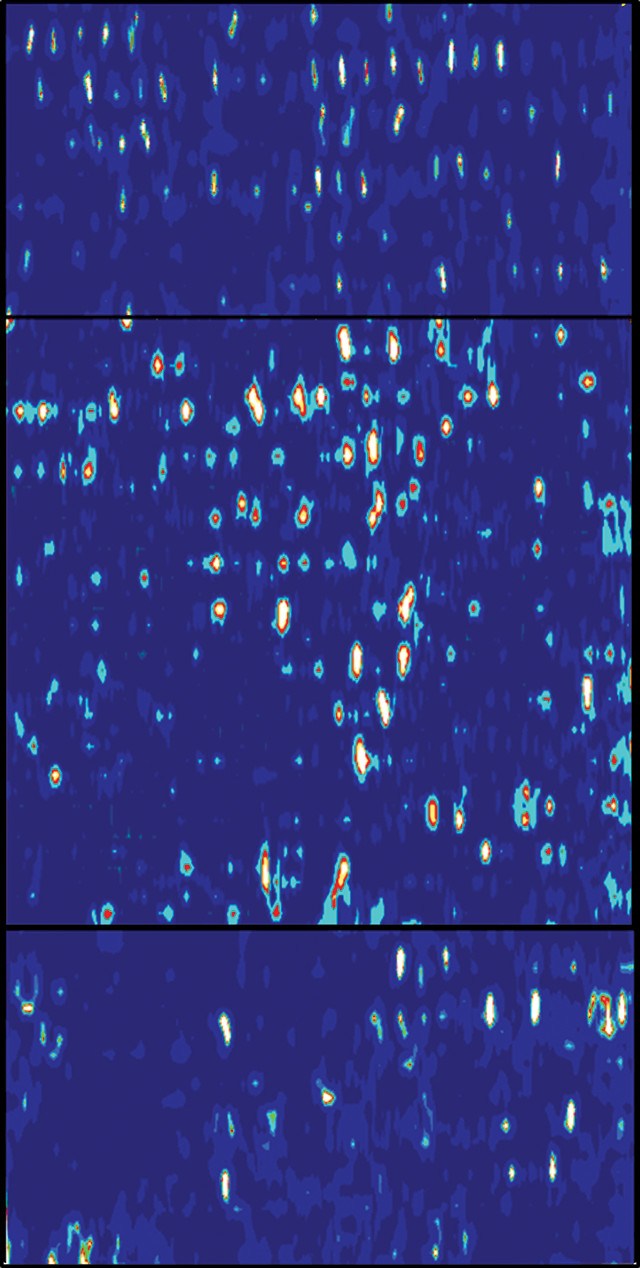

Ground-penetrating radar data, in map view, indicates dozens of likely burials at Holy Mother of the Rosary Cemetery in Cheektowaga, N.Y., in an area where only a handful of grave markers were visible on the surface. Credit: Kevin Williams.

In summer 2014, Williams and Trevor Jennings, an undergraduate at Buffalo State, spent four days at each cemetery collecting three-dimensional ground penetrating radar (GPR). The technique, which has been employed on occasion to detect unmarked gravesites, entailed carefully walking a wheeled radar unit along grids of transects. The radar signal reflects off interfaces between materials or layers of different density — say, between disturbed and compacted soil, or between soil and a casket — providing rough images of what’s below the surface.

The pair found numerous indications of potential burials. Just looking at two-dimensional depth profiles from their GPR data, they saw reflections similar to those you’d expect from boulders or other objects buried in the soil, Williams says. But adding in the third dimension, parallel to the ground surface, improved the view substantially. With this perspective, many of the reflections appeared cigar-shaped — about what you would expect from human burials. “You can also look at the orientations and spacing [of the reflections], and that improves your confidence in your interpretation,” Williams adds.

In one 820-square-meter parcel at Holy Mother of the Rosary Cemetery, where just five grave markers were visible, Williams reported at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA) last fall in Baltimore that he and Jennings were “confident” of 99 burial sites, labeling dozens of others as “likely” or “possible” burials as well. It’s not clear what became of the rest of the markers, but some were probably wooden crosses or plaques that deteriorated over the years, while others may have been buried, Williams noted in his talk at GSA.

The administrators at Holy Mother were “kind of shocked” when they saw the results, Williams says, “but shocked in a good way.” Now, the cemeteries can update their records to mark spaces that are or are not empty. Unfortunately, GPR doesn’t help uncover the identities of those buried in the unmarked sites, although Williams says differences in the sizes and spacing of reflections offer clues as to whether graves hold adults or children.

The cemetery visits have also offered student learning and outreach opportunities. While Williams and Jennings collected GPR data, his colleague at Buffalo State, anthropologist Lisa Anselmi, led students from the college’s archaeological field school through hands-on training in surveying and record-keeping methods. And when the team has been at the cemeteries, Williams says, people have also “come out to see what we’re doing, and we’re able to educate them about the equipment and the earth science side of things.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.