by David B. Williams Thursday, November 19, 2015

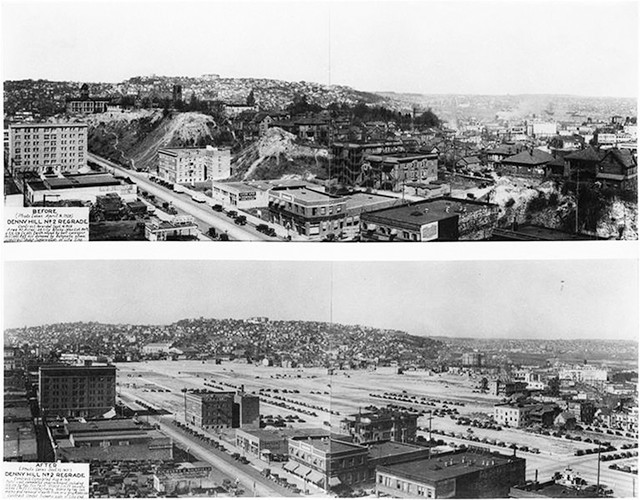

The Denny Hill area shown in 1928 before the final regrade project began and after it was completed in 1931. Credit: courtesy of Seattle Municipal Archives, Image 9331.

Seattle city engineer Reginald H. Thomson may have been the driving force behind the Denny Hill regrades, but they could not have occurred without public support. In order for a regrade to proceed, at least 50 percent of the people who lived in the affected areas had to sign a petition. For example, the Second Avenue regrade needed the signatures of 67 property owners. A completed petition triggered the next phase, which was a city council ordinance that defined the boundaries of the regrade. A second ordinance then provided the funding mechanism, or what was known as a Local Improvement District (LID).

The LID made the landowners pay for the improvement of their own property, as opposed to distributing the cost across the city’s taxpayers. How much a property owner owed was based on a simple formula. On the plus side was the appraised value before the regrade; the owner would be paid for any buildings destroyed during the project. The owner would also add to the plus column any theoretical damages to the property caused by lowering the street. On the negative side were the costs of rebuilding the infrastructure, which was divided among all who benefited, in proportion to how much their property would benefit. In order to determine these values, a judge appointed a commission, which held a series of public meetings, visited the properties and sent out inquiry letters.

Many perceived the process to be unfair, or at least arbitrary. The commission made mistakes and probably was influenced by politics, but many of the poor decisions were corrected on appeal, and just a handful of cases made it all the way to the State Supreme Court. Homeowners had 10 years to pay back their assessments, with rather steep 6 percent interest. Plus, they had to pay taxes on the new, usually higher assessed value of the land. They also had to pay the contractor separately for lowering their property.

Many of Denny Hill’s residents had agreed to the project because, once lowered, their properties would be more commercially viable, and most of them hoped to turn a profit selling to businesses. Only a handful of residents restored or rebuilt homes on their plots. However, as the project concluded, the Great Depression loomed, and it’s likely that many of them never realized the financial gain for which they’d hoped.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.