by Lon Abbott Thursday, March 22, 2018

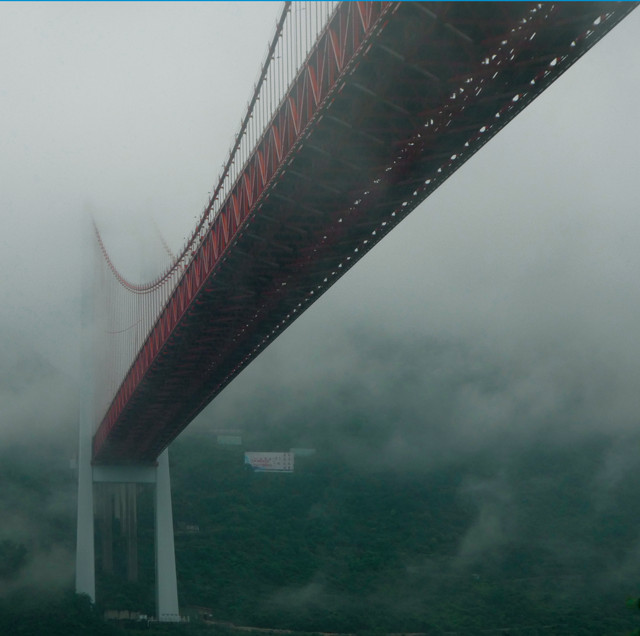

Guizhou Province is known for its stunning karst topography. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/KingWu.

As I admired an immaculately preserved colony of 230-million-year-old crinoids lying next to an equally impressive skeleton of a sharp-toothed ichthyosaur at China’s Guanling Fossil Group National Geopark, I thought back to family trips to North American national parks during my youth. The natural wonders I saw on those trips strongly influenced my career choice and shaped my perception of how humans fit into Earth’s long history. Today, even after more than 35 years spent studying the Earth, every visit to a spectacular natural site like this one in Guanling still engenders the same excitement and insight I had as a youngster.

For many travelers, myself included, geotourism is an integral aspect of every trip we take; through our journeys, we witness Earth’s majesty and try to better understand the story of our planet’s evolution. The concept of geoheritage recognizes that some places are special because of their geologic attributes, and that those attributes influenced human history and culture.

The idea of protecting and celebrating geoheritage is not new. But designating noteworthy geoheritage sites as “geoparks” only originated in the mid-1990s. By 2000, the first official geoparks were established, with China instituting a national geopark program, and four different geosites in Europe collaborating to form the European Geoparks Network. Together the Chinese and the Europeans formed the Global Geoparks Network in 2004, which initially included 25 geoparks, all in China or Europe. The network headquarters was established in Beijing.

In 2015, UNESCO, better known for promoting World Heritage sites (locales designated based on cultural or natural value, or a mix of both), formally endorsed the designation of UNESCO Global Geoparks after providing ad hoc support to the geopark movement for years. Today, 127 such geoparks can be found in 35 countries. China hosts 35 Global Geoparks, more than triple the 11 found in Spain, which ranks second. China currently has 52 World Heritage sites, ranking it second in the world behind Italy, and it is seeking more such designations, including for Guanling.

I visited Guanling National Geopark in Southwest China’s Guizhou Province in 2017 to attend a symposium organized by local officials as part of their effort to earn World Heritage status for the Guanling fossil locations. A number of renowned experts on Triassic paleontology were invited to speak about the Guanling biota’s world-class significance, and I was asked to review the criteria used by external reviewers in assessing the merits of candidate sites during the World Heritage site evaluation process.

In 2017, geoscientists from around the world, including plesiosaur expert James Neenan (center) and the author (not pictured), traveled to Guizhou Province to attend a conference organized by local officials — some of whom are shown here in the traditional dress of several Guizhou minority groups — as part of an effort to earn World Heritage status for Guanling fossil locations. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Although China has a reputation for sacrificing its environment in the name of progress, its pace of landscape protection has been as dizzying as its pace of development, and the country has emerged as a global leader in geoheritage preservation. In 1982, the country had no national parks; today, China boasts 208, compared with 139 national parks and monuments in the U.S., which has a similar land area. The number of Chinese national geoparks has risen even faster: After the establishment of the first national geoparks in 2000, the country now has 239.

Guizhou provides a microcosm that clearly illustrates the goals and approaches that China uses to recognize and protect its geoheritage. The province occupies a large tract of the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, a hilly area ranging from 500 to 2,500 meters in elevation that lies between the lowlands to the east and the Tibetan Plateau to the west.

Guizhou's Loong Palace National Park is one of China's 208 national parks. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

A thick stack of Paleozoic- to Mesozoic-aged limestone underlies most of the plateau. Given that the region’s abundant rain easily dissolves this limestone, the province boasts a spectacular karst landscape of caves, sinkholes and rugged limestone spires. The rain also feeds major rivers that slice deep gorges into the plateau, historically making transit across the province a difficult, and time-consuming, affair. In large part because of its rugged topography, Guizhou has remained one of the country’s poorest provinces. Its combination of mountains, rain and poverty inspired the well-known saying in China that Guizhou is a place with “not three feet of flat land, not three days without rain, and not a family with three silver coins.” It is also one of China’s most ethnically diverse provinces, with 17 different minority groups making up 37 percent of the province’s total population of 35 million.

Abundant rain has carved the limestone of the Guizhou Plateau into a dramatic karst landscape. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Government planners have long sought to boost economic development in Guizhou to combat the province’s poverty. Given Guizhou’s stunning scenery and cultural diversity, planners have identified the growing international trends of geotourism and cultural tourism as vehicles to achieve that goal. They also quickly recognized that the province’s transportation infrastructure would need improvement if there were any hope of increasing tourism.

They started by building a modern highway with dozens of costly bridges and tunnels, which are necessary to efficiently traverse the rugged topography. Prior to the 2009 completion of the motorway, the 150-kilometer trip from the airport at Guiyang, the provincial capital, to Guanling took almost an entire day. Today, it takes a mere two hours. Just east of Guanling, the road crosses the Baling River Bridge, which soars 370 meters above its namesake river. When it opened in 2009, this structure was the highest road bridge in the world; it now ranks seventh. Nine of the world’s 10 highest bridges are in China, with seven of these in Guizhou, including the current record holder, the 565-meter-high Duge Bridge completed in 2016.

Guanling’s fortunes have risen along with development of the transportation infrastructure and the tourism it has brought. Paleobiologist Hans Hagdorn, an expert on crinoids, says “Guanling has changed dramatically” since he first visited in 2002. “Complete parts of the old village have been torn down and rebuilt. A complete new part with a hotel and administrative buildings was erected close to the town entrance [near] the motorway.” In 2002, unlike today, the locals also weren’t accustomed to seeing Westerners. When Hagdorn and two colleagues headed downtown to phone their families, “more than 100 people came to see us. Obviously, they had never seen ‘longnoses’ — the Chinese nickname for Westerners — before. They stood with open mouths staring at us,” he says.

The Huajiang River has carved one of the deepest gorges in the Guanling area, known as the Huajiang Grand Canyon. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

The title of the conference I attended, “The International Symposium of Guanling Biota Protection and Featured Regional Touristic Development,” says it all with regard to the local organizers’ twin objectives. But how compatible are the goals of geoheritage preservation and economic development?

In 2016, 184,000 foreign tourists visited Guizhou, a 10 percent increase above 2015. Meanwhile, the region hosted more than 100 million Chinese tourists. But it could be even more. Nearby Yunnan Province, which boasts similar spectacular karst topography and cultural diversity, receives far more tourists — a whopping 5.7 million international visitors and almost double the number of domestic tourists. During “Golden Week” each year, during which Chinese National Day (Oct. 1) falls, everyone gets a three-day holiday. Last year, more than 710 million Chinese traveled that week.

Travel times in Guizhou have plummeted thanks to construction during the last decade of motorways replete with numerous expensive bridges and tunnels. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/4045.

Guizhou is working to attract more visitors, both foreign and domestic. One example of the strategy to attract more overseas visitors is its hosting of the 2017 American Society of Travel Agents (ASTA) China Summit, the first ASTA meeting focused on promoting China as a tourist destination. More than 130 U.S. travel agents and 200 Chinese tour operators attended the summit. Hou Ying, chairman of China’s ASTA branch, noted in an article in China Daily newspaper that Guizhou, with its stunning karst scenery and multiple ethnic minorities, will appeal to American travelers who want to experience different cultures, landscapes and foods. In hopes of boosting American tourism, the province decreed that U.S. citizens can visit most Guiyang tourist attractions for free and that they’ll receive a 25 percent discount at the city’s hot springs throughout 2018.

As for domestic tourists, Guizhou officials are hoping to take advantage of the province’s comparatively cool climate by enticing summer tourists from China’s warmest cities. The province offered 50 percent discounts on highway tolls and entrance fees to most Guizhou tourist attractions to visitors from China’s 10 warmest provinces between mid-July and mid-September 2017.

The Baling River Bridge was the highest in the world when it was completed in 2009. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

But tourism doesn’t always produce economic benefits for local communities, a phenomenon evident in Yunnan, where despite an influx of tourism, rural poverty has not decreased, so it is important to examine Guizhou’s brand of geotourism more deeply. Too often, tourist money flows through a community, rather than into it, ending up in the deep pockets of distant developers. In 2007, political scientist John Donaldson of the Singapore Management University conducted a study of the effects of tourism on rural poverty reduction in Guizhou compared to Yunnan. Yunnan’s economic growth has, thanks mainly to its large tourism sector, far outpaced that of Guizhou since the 1990s. But Donaldson found that Yunnan’s rural poverty rate had barely budged, even with its concentration of rural tourist attractions. Despite its comparatively small size, Guizhou’s tourist industry meanwhile has injected money into local economies so successfully that the province, which in the 1990s had a higher rural poverty rate than Yunnan, has dropped below its neighbor in the rankings. Furthermore, average wages in Guanling increased 200 percent between 2004, when the Guanling Fossil Group National Geopark was designated, and 2010. As droves of people came to admire the fossils in the newly constructed museum, geotourism clearly benefited rural economies in Guizhou — and it has the potential to boost them further.

The tollbooth at the motorway's Guanling exit celebrates the area's Triassic fauna. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

China has an extensive list of provincial- and national-level designations for protected sites, each with its own set of qualifying rules as well as restrictions on activities that can be carried out within the protected area. When it comes to protecting geoheritage sites, the two main vehicles at the national level are national parks and national geoparks. These designations are not mutually exclusive, and some sites, such as Zhijin Cave, 190 kilometers north of Guanling, qualify as both. Zhijin Cave also recently became Guizhou’s first UNESCO Global Geopark, a designation that provincial tourism officials tout widely. Officials value any type of international recognition for their tourist sites because it gives the site a leg up in the fierce competition for tourists.

In 2002, the fossiliferous outcrop at Wolonggong Hill, which would later become the Guanling Fossil Group National Geopark, hosted only farms. Tourism to the site since its designation in 2004 has increased the average local wage in Guanling by 200 percent. Credit: Hans Hagdorn.

While in Guizhou, I visited two national parks near Guanling, both of which protect impressive examples of the region’s beautiful karst. Loong (Dragon) Palace National Park is a 60-square-kilometer park located 47 kilometers from Guanling that protects China’s longest underground river, a 5-kilometer-long stream that flows beneath 30 karst hills and connects 90 separate caves. The underground river emerges briefly at tranquil Tianchi Lake, which fills a sinkhole formed from a collapsed cave, before plunging over the 34-meter-high Dragon Gate Falls, which locals describe as resembling a white dragon leaving its lair.

Loong Palace National Park also highlights the culture of the Bouyei ethnic group that inhabits the nearby villages, including the protected village of Yunshan, which looks much the same as it did during the Ming Dynasty. Visitors can listen to a Bouyei band at Tianchi Lake while they ponder an intriguing tidbit highlighted prominently in the park literature and on an interpretive sign: Tianchi Lake has been certified by the China Atomic Energy Authority as the place with the world’s lowest radiation dose.

Yunshan village, near Loong Palace National Park, looks much the way it did during the Ming Dynasty in the 1600s. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Park visitors board boats for an underground river cruise through one of the longest of the 90 caves, which is colorfully lit. The experience has more parallels to a theme park visit than a trip to a U.S. speleological park, such as Mammoth Cave or Carlsbad Caverns, but the national park designation protects the scenic landscape from encroachment by the 20-story apartment buildings that are quickly sprouting up all around its borders.

The river that runs through Loong Palace National Park connects many different caves. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Nearby Huangguoshu National Park, which is only 25 kilometers from Guanling and, like Guanling Geopark, is currently seeking World Heritage status, features the 78-meter-high Huangguoshu Waterfall, the tallest in China. Its scenery is often compared to 50-meter-high Niagara Falls, and the hustle and bustle of the tourist town at its base is comparable as well.

All Chinese tourist attractions receive quality ratings from the China National Tourism Administration. Huangguoshu is rated as an AAAAA scenic site, the highest rating. Such designations are based on 12 criteria, one of which is the comprehensiveness of the site’s conservation plan. Other criteria reflect the economic development goals that are an integral part of most preservation efforts in China and rate how popular the attraction is to visitors, how much tourist infrastructure exists, and how easy it is to reach the site, among other factors. Although a national park designation for a Chinese geoheritage site conveys significant protection, it doesn’t mean the site is necessarily managed to maintain a pristine state to the extent possible, which is the goal in U.S. national parks.

The 78-meter-high Huangguoshu Falls is the tallest waterfall in China. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

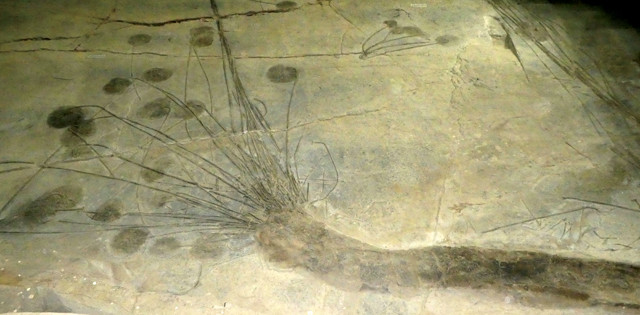

The crinoids and the ichthyosaurs that I admired at the Guanling Fossil Group National Geopark belong to the Guanling biota, a Late Triassic fossil locality with exceptional preservation. The biota, in combination with several other extraordinary Early to Late Triassic fossil sites spread throughout southern China, provide the world’s best record of the pace and trajectory of life’s recovery after its most acute crisis, the end-Permian mass extinction. Peking University professor Jiang Da-yong, a leading expert on Triassic paleontology who has been studying the Guanling biota and working to protect these fossils since 2000, notes that the Guanling biota yields “abundant, complete and well-preserved marine reptiles, crinoids, bivalves, ammonites and other fossils, [making it] a marker of the fully recovered marine ecosystem after the end-Permian mass extinction.”

Guanling National Geopark boasts several complete, spectacularly preserved ichthyosaurs that are displayed in the spots where they were discovered. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

This locale first attracted the attention of Chinese paleontologists in 1995, when local farmers brought them to a place where they had been digging up beautifully preserved crinoids, ammonites and vertebrates to sell at fossil markets. Jiang was delighted with the 2003 designation of the site as a provincial geopark and its 2004 elevation to a national geopark because such designation promotes sustainable tourism — meaning that his and other paleontologists’ research “can feed back to local communities” while simultaneously preventing the loss to science that had been occurring when fossils were being damaged during amateur excavation and sold illegally on the private market. Jiang says he anticipates that if the site receives World Heritage status, the fossils will be “protected even more strictly and more foreign scientists may pay attention to the site, which will lead to further good research.” He also sees it as boosting the local economy because it will be “beneficial to tourist businesses and attract more visitors.”

During the Triassic, colonies of crinoids floated across the oceans attached to driftwood logs. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Jiang points proudly to the geopark’s museum, whose multimedia exhibits make it “a good education site for students to learn about geoscience, fossils and past life.” I heartily agree with him; while visiting the geopark, I learned a lot about Triassic biology. For instance, ichthyosaurs, the top predators in Triassic seas, evolved from a group of land reptiles that returned to the seas in the same way that, much later in Earth history, whales would evolve from ancestral land mammals.

I’ve seen live crinoids, which are stalked, sessile animals that feed by filtering organic matter from seawater with their many feather-like arms, rooted to the modern deep seafloor during dives in the Alvin research submersible. But the Guanling crinoids weren’t rooted to the seafloor; rather they were attached to pieces of driftwood. Having always thought of crinoids as benthic animals, I was especially captivated by the mental image of crinoid-encrusted logs drifting through Triassic seas. When I asked Hagdorn why I’ve never seen a modern crinoid-encrusted driftwood raft, he told me that such rafts were likely commonplace from the Middle Triassic to the Early Jurassic but disappeared after this time when wood-boring mollusks known as “shipworms” evolved. The shipworms dramatically reduced driftwood’s longevity, making them unsuitable homes for crinoids. The wonders of our planet’s evolution never cease to amaze me.

China's Buddhist heritage is evident in the many Buddha statues that adorn Guizhou's karst caves. Credit: Lon Abbott and Terri Cook.

Tom Casadevall, chair of the U.S. Geoheritage and Geoparks Advisory Group, has worked extensively with Chinese colleagues on geoheritage issues; he says that the U.S., which currently lacks a national geopark program, can learn much from China’s geopark experience. China, he adds, is a rising power in nearly all international scientific organizations, including the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), the umbrella organization that coordinates geoheritage preservation and the establishment of geoparks. “China contributed money and staff, and built a building, so IUGS moved to Beijing,” he says. Casadevall traveled to Guizhou in December 2017 to consult with Chinese counterparts about international perspectives on geoheritage protection and to learn what it takes to establish a successful national geopark program.

I asked Jiang what other regions and countries can learn about geoheritage protection from the experience gained during the establishment of the Guanling National Geopark and the ongoing efforts to earn it a World Heritage designation. “The [Anshun] city and [Guanling] county governments really take it seriously and have a special and professional office to do the work,” he says. He also lauds the local governments’ international focus: “They are very open to the world, establishing partnerships with relevant sites in Germany and Switzerland, and taking part in international conferences to give posters and talks about the Guanling biota. I think other sites should learn from Anshun and Guanling in this way.”

Given the province’s documented success in harnessing culturally based tourism and geotourism to help lift its residents out of poverty, Guizhou serves as a model for the world in how to achieve a harmonious synergy of geoheritage resource protection and sustainable economic development. I hope that sites like Guanling National Geopark can inspire the next generation of geoscientists in China the way visits to U.S. national parks inspired me.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.