by Mary Caperton Morton Monday, July 6, 2015

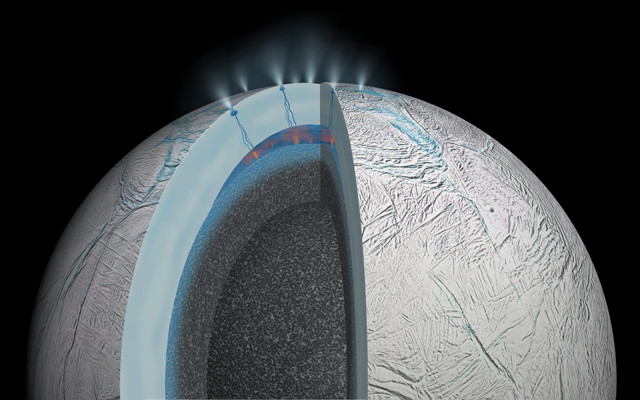

Interactions between deep ocean water and hot rock on Saturn's moon Enceladus are thought to result in hydrothermal plumes that erupt through the moon's icy crust. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Jupiter and Saturn are both gas giants boasting multiple moons. Now, two separate studies have identified another similarity: Each appears to have a moon with hidden underground oceans.

Jupiter’s moon Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system and is the only moon with its own magnetic field, which frequently sparks glowing aurorae encircling the moon’s north and south poles. Ganymede’s close proximity to Jupiter means that the moon is also embedded within Jupiter’s magnetic field, and when Jupiter’s magnetic field shifts, the aurorae on Ganymede do too, rocking back and forth.

Using the Hubble space telescope to observe ultraviolet light emanating from the aurorae, scientists found, however, that the aurorae weren’t moving as much as expected. The team, led by Joachim Saur of the University of Cologne in Germany, determined that a large ocean of electrically conductive saltwater beneath Ganymede’s crust is likely counteracting the influence of Jupiter’s magnetic field on the aurora. Specifically, the researchers reported in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, Ganymede’s ocean is probably about 100 kilometers deep — roughly 10 times thicker than Earth’s oceans — and buried under a 150-kilometer-thick crust of ice. They also noted that the new method using Hubble to track the movement of aurorae could be useful to look for evidence of water on distant planets.

In addition to Ganymede, Saturn’s satellite, Enceladus, may also have a vast reservoir of underground water. New gravitational field measurements, reported in Nature, suggest a body of water about 10 kilometers thick, under a layer of ice between 30 and 40 kilometers thick.

Observations by the Cassini spacecraft of Saturn’s E-ring — the second most outer ring, which is thought to be produced from debris from Enceladus — revealed a wealth of silicon-rich dust particles. The size and composition of the particles suggest that they may be produced by high-temperature reactions on the moon’s ocean floor. The particles must then make their way up through the ice to join the giant plume of gas, ice and dust that erupts from Enceladus’ south pole to form the E-ring.

The finding, reported by Hsiang-Wen Hsu of the University of Colorado at Boulder and colleagues, is the first evidence of ongoing hydrothermal activity in our solar system other than on Earth.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.