by Sam Lemonick Thursday, January 5, 2012

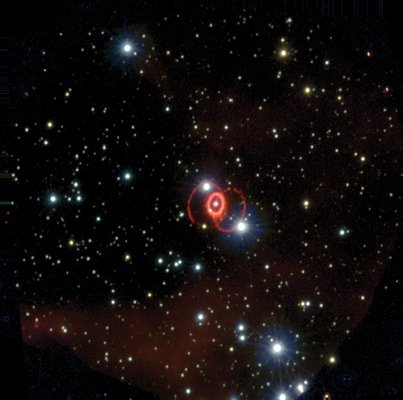

Three glowing gas rings around supernova 1987A. P. Challis

Jason Marsh is done waiting around for someone else to transport him into space.

Marsh, a system administrator near Washington, D.C., is preparing to launch a new website for his Open Space Movement (OSM — currently here), a nonprofit project that aims to be a platform for developing and funding aerospace technology — and will be open to anyone who wants to join in.

The OSM already has about 700 members from around the world, a community that Marsh hopes will grow after the website’s launch. His ideas for new technologies and designs range from the grand — plans for a modular space station — to the most basic — a drill that will help to put the station together. And the timing of the website coincides nicely with the planned launch of the first amateur rocket, a rocket designed and built by Denmark's Copenhagen Suborbitals and a project the OSM is helping to fund.

EARTH contributing writer Sam Lemonick talked with Marsh about his vision for the future of aerospace engineering and exploration, and how to open space up to anyone who wants to go.

JM: [We’re] basically applying open source principles to aerospace engineering. Specifically [we’re] trying to repeat the success of Linux and the growth of the Internet, things that are funded largely by the public … and not necessarily in the domain of government agencies or strictly pushed out by private industry.

It’s something to give people an alternative to the hopelessness of space exploration. The only two [currently] perceived ways of being involved in space are as an astronaut or as a tourist. Those two by themselves don’t generate a whole lot of public interest because most people aren't on the astronaut track and don't have $30 million to spend on a round-trip ticket.

JM: The project development, the funding scheme and the scheme for voting for projects or for funding requests or OSM policy is completely transparent [and] designed to be interacted with. If you want to send us some money, there you go. If you want to have a say in where that money goes, get in here and vote on which project you want to see funded, or vote for OSM policy. It's a human-powered system.

The funding model is split up into three parts. One is OSM operations, just the basic paying-the bills-type stuff. The second, [OSM’s] projects, would normally be getting the lion's share of the funding but at the moment we aren't set up to produce projects. If we did have some projects they'd have to go through some peer review before we could deem them fundable.

The one thing we can do at the moment is a grant, and that's one of things we thought about in the past: that we could put money toward projects, but what about people who already have their own thing going, that don't necessarily need to use our system? What's the one thing we can do for them? Send them some money.

One of the [important] things is not expecting people to come in and out of the goodness of their hearts help space access, because that's just really not going to happen. However, if you start making incentives for things then you start seeing that explosive growth. These incentives are not [necessarily] monetary or reward-based — one of the big incentives [for users] is being able to show off their creativity.

Even though this is like a perfect storm for dumb ideas, those dumb ideas teach people what works and what doesn't work and it's fun for them. It's something enjoyable they can do. We could potentially become the biggest reason for college students staying up past 4 a.m., past Warcraft or Farmville or whatever.

JM: Changing people's perceptions about space in general and offering involvement. The two kind of go hand in hand — if you work with us and if everybody gets together, we can direct a lot more energy, creativity, manpower and monetary resources than any existing private or government space program right now. It's just a matter of giving a direction and organization for that and that's where we fall in.

We're a platform for everyone else to use: Let them produce their own content, let them work with us, let other existing space organizations work with us, be they the smaller, open source ones or the established commercial ones. We aim to find a way to help everybody work in the same direction for a common goal, and the common goal is more or less to run ourselves out of business, making space [travel] happen in a matter of years so we don't need to have an OSM anymore.

JM: ITAR [the United States’ International Trafficking in Arms Regulations] prohibits sharing of info unless it’s strictly academic or not developed under the auspices of a U.S. entity. That kind of knocks out a lot of the free sharing from the established U.S. companies. They really can't just give out things to an organization like us that aims to be colorblind to nationality. Out of 700 [members], a good hundred of them are probably from countries other than the U.S. — Australia, Great Britain, Denmark — for example, Copenhagen Suborbitals.

It stands to reason that we could possibly start producing more of a groundwork of open source-type stuff that skirts away from being classified as ITAR-controlled. That's one thing that would be very beneficial for everybody working toward space in the near future.

[In reality] anything that could be used to guide a satellite could be used to guide a rocket into someone's house. So we have a little bit of a challenge with the ITAR thing. We will need space lawyers, let's put it that way.

JM: I haven't met anyone who's doing anything exactly like the OSM. There have been some ideas that carry on certain aspects of the OSM. When I talk to Gary Barnhard, [executive director] of the National Space Society, he does say he's seen a lot of ideas inside NASA and elsewhere that mirror certain aspects of the OSM. We both agree that the OSM is a very cohesive way of tying a lot of those together and actually making a very robust platform for supporting a lot of things in a lot of different directions. That's kind of the key to overcoming the critical mass toward becoming something that's interesting to hobbyists versus interesting to the public at large.

JM: As it is right now we basically have an organic growth model. We aren't really tied to meeting any specific benchmarks. The only sizable step is actually launching the site and getting all the bugs worked out and getting the initial population. But after that it should basically work by itself. Mr. Barnhard and I kind of contemplated that after a certain point we'll reach a kind of black hole-type growth.

JM: The inspiration for this was Linux and the whole open source movement. Back in 1999, when Linux was gaining a lot of traction, I was thinking, "I can see where this is going. I wonder if space could do the same thing?"

The OSM itself wasn't so much the main idea. I think I had some other ideas for a modular space container and I started thinking, “How can I get this developed better?" [I thought], “Let's have a giant social-network-type development environment help hammer this out, and help hammer out all the other little ideas that help support it.”

[It’s not] so much for personal glory or something like that. It's more for the future of humanity. It kind of [came] from a realization that you don't have to be famous to make history, you just need a little elbow grease.

JM: When I talked to Christian von Bergstrom of Copenhagen Suborbitals I outlined some of the stipulations that we have — we want to have the ability to publish the results that were helped out by our donation, we would like the right to royalty-free use of any technologies derived from our grant, specifically for OSM nonprofit use, and we would like to see what the money's being used for. [Finally] we wanted to make sure that if they were deficient in personal protection equipment or HAZMAT things or facility maintenance, [they solved] that first before spending more money on rocket fuel.

JM: We do want to work with NASA because they have a whole lot of interesting information out there and it would be pretty foolish to just ignore all of that. I was talking to one of the fellows over at NASA's NASApedia program that they're working on developing and we're planning on sharing the data once they're up and ready to release.

That's partially good, [but] a data dump of NASA's archives is not the most readable thing. One of the things we can do is analyze all this stuff and produce it in a more digestible format for everyone else. [We can] find stuff that hasn't been updated since the '70s and rehash or rewrite it or add it as a footnote. We can bring things up to standard and work on indexing a lot of this information, making it easier to find, adding hash tags or markers or metadata to the existing structure. [We can also come] up with a sequence of, "You should read this, this and this before you start reading this," making a guide for someone with no experience. Education is going to be a key thing.

JM: People don't place a lot of faith in NASA as the go-to point for seeing space in their lifetimes. It's not so much a failing of NASA, it's just that they're not really designed for that. They're great for a regulatory body and for the research and development but asking them to fund something like putting private citizens into space, that's not really feasible.

That's where you actually have to get markets to develop. This is one of the little epiphanies that occurred to me — if you had enough people involved who were interested in this, then you could make your own market. If you make your own market and you make it big enough, you can dictate where everyone else is going to go and make everyone else fall in line.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.