by Mary Caperton Morton Monday, February 2, 2015

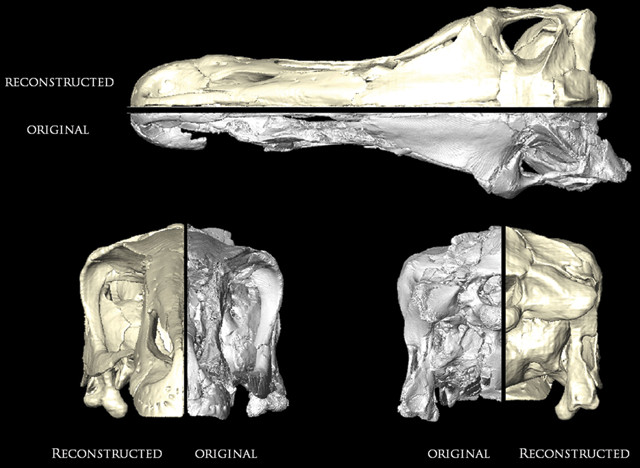

A comparison between the originally preserved and digitally restored skulls of the Cretaceous dinosaur Erlikosaurus andrewsi. Credit: Lautenschlager et al., 2014, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (6).

Some dinosaur species are only known from a single skull, and gaining access to study such rare and fragile fossils can be difficult, especially if the skull is stored in a far-flung place like a museum in Mongolia. Now, a new technique using medical CT scans and digital imaging to create a digital model of fossils will allow such rarities to be studied by lots of eyes, all over the world, without damaging or transporting the delicate original.

The technique was described in a new study in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology that focuses on the skull of Erlikosaurus andrewsi, a 4-meter-long herbivore that lived in Mongolia about 90 million years ago. “This fossil is from a very curious type of dinosaur; it’s extremely rare, and the skull is normally quite hard to get ahold of,” says Stephan Lautenschlager, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England and lead author of the new study.

Given a rare opportunity to study the skull by the Geological Institute of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences in Ulan Bator, Lautenschlager and colleagues took detailed scans of the fossil using high-resolution X-ray computed tomography, also known as CT scanning, which they used to create a digital model of the fossil.

Once they had the model, the team was able to study the Erlikosaurus skull in ways that would not be possible with the fragile original, Lautenschlager says, including virtually disassembling it into its individual elements and digitally filling in any breaks and cracks in the bones.

The team was also able to duplicate elements missing from one side of the skull but present on the other using mirroring techniques, and to remove deformations in the skull that occurred during fossilization by digitally reversing these effects. In a final step, all of the reconstructed elements were then re-assembled.

Combining CT scans and digital imaging “is a really powerful tool that gets us a step closer to restoring fossil animals to their original lifelike condition,” Lautenschlager says. CT scanning has been used on much younger fossils in the field of anthropology for years, but the technique is relatively new to paleontology, he says.

“The recent advances in using CT scans on fossils are mainly in the software, which has become cheaper and easier to use, resulting in more visually impressive images,” says James Clark, a paleontologist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the new study. The fossil studied in this work probably “wasn’t particularly challenging to scan … but the processing of the images was very impressive.”

Digital models may eventually be used to create digital databases of rare and unusual fossils, but for now the process remains time consuming overall: The CT scans can be done in a matter of hours, but reconstruction of the Erlikosaurus skull by Lautenschlager’s team took about three months.

“At the moment, there are no [standardized] protocols in place for creating these models,” Lautenschlager says. “As we learn more about using this technique, hopefully people will come up with different tools to speed up the process.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.