by Cassandra Willyard Thursday, January 5, 2012

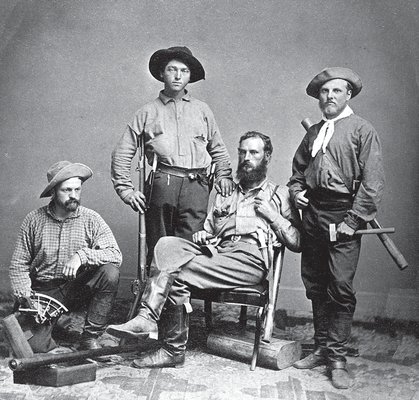

Clarence King (far right) - who later became head of the U.S. Geological Survey - and his men helped foil one of the boldest prospecting hoaxes in history. U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library

On a foggy day in 1871, two men walked into the Bank of California in San Francisco. One held a rifle and the other gripped a large buckskin pouch. Both were covered in a thick layer of grime. Initially, the nervous teller took the shady drifters for bank robbers. But his anxiety turned to elation when they showed him the contents of their pouch — a shimmery bounty of diamonds, rubies and sapphires.

So begins Sam North’s novel, “Diamonds: The Rush of ‘72,” a book that describes one of the most audacious prospecting hoaxes in history. Although North’s account is fictional, his plot is anything but. The men North describes, Philip Arnold and John Slack — conniving cousins from rural Kentucky — were real, and so was the elaborate fraud they perpetrated.

Arnold and Slack’s story begins in 1870 in California. The Gold Rush was winding down, but the state was still filled with hopeful prospectors. Arnold and Slack, their heads filled with tales of men striking it rich in South Africa’s diamond fields, set out to unearth American diamonds. Finding none, they settled for the next best thing: If they couldn’t get rich by discovering diamonds, they would get rich by making people think they had discovered diamonds.

First, the two conmen amassed a collection of poor-quality uncut diamonds and other precious gems. Robert Wilson, who wrote about the hoax for Smithsonian magazine in 2004, speculates that the diamonds came from the Diamond Drill Co., where Arnold worked as an assistant bookkeeper, and that the other gems were likely purchased in Arizona. By some accounts, the men took this treasure to the bank to deposit. Wilson reports that they took it to George Roberts, a San Francisco businessman. Either way, word of their discovery got out.

The diamond rumors, combined with Arnold and Slack’s reluctance to discuss where the riches came from, were enough to lure in William Ralston, owner of the Bank of California, and two army generals. They banded together with Roberts and a few other entrepreneurs and set out to acquire the rights to Arnold and Slack’s seemingly rich claim. Meanwhile, Arnold and Slack traveled to England, where they paid $20,000 to secure another bag of uncut gems.

At first, Ralston and his pals held their excitement in check: The gems, after all, could be fakes. With Arnold and Slack’s permission, they brought 10 percent of the pair’s latest “find” to New York City. There they enlisted the help of Charles Lewis Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & Co. Although the gems were worth at most only a few thousand dollars, Tiffany mistakenly valued them at $150,000.

Arnold and Slack were no doubt ecstatic. But they still had one major hurdle. The investors would certainly want to see the men’s claim before putting down serious money. So Arnold again traveled to England to buy more gems, which he and his partner sprinkled liberally across a dusty patch of ground along the Colorado-Wyoming border.

The investors, accompanied by their mining engineer and Arnold and Slack, arrived at the site on June 4, 1872. They found diamonds in abundance, along with rubies, emeralds and sapphires. Even the mining engineer was convinced. Soon after, the investors handed the devious duo cash and shares of stock amounting to more than $600,000 (approximately $10.5 million in today’s dollars).

The fraud wasn’t exposed until the fall of 1872, when the investors’ men encountered surveyors working for the federal government. The surveyors — led by Clarence King, an adventurer and Yale-trained geologist — began to suspect that the men’s riches had come from the 200,000-square-kilometer area they had already surveyed. Worried that a big discovery in the area would make government officials question their meticulousness, King and his colleagues decided to check out the “mine” for themselves.

After some sleuthing, the surveyors uncovered the mine’s whereabouts and started digging. They found many gems, but the pattern was unnatural: For every diamond King found, he located 12 rubies. When the men dug deeper, they found no gems at all. Also telling was the fact that the men unearthed gems that never naturally occur in the same place. King took news of the fraud to the investors, who were crushed.

The news hit the papers on Nov. 26, 1872. The New York Times, which had suspected fraud all along, was understandably self-righteous: In an article published on Dec. 6, reporters wrote that the most remarkable part of the scam was that the perpetrators had succeeded “in deceiving business men and capitalists so proverbially shrewd as those of San Francisco.”

Arnold was tracked to Kentucky and eventually forced to return the investors’ money, but Slack was never found. Three years after the hoax was exposed, Ralston committed suicide. In 1879, King, by then a local legend, became the founding director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.