by Lauren Herbine Friday, January 5, 2018

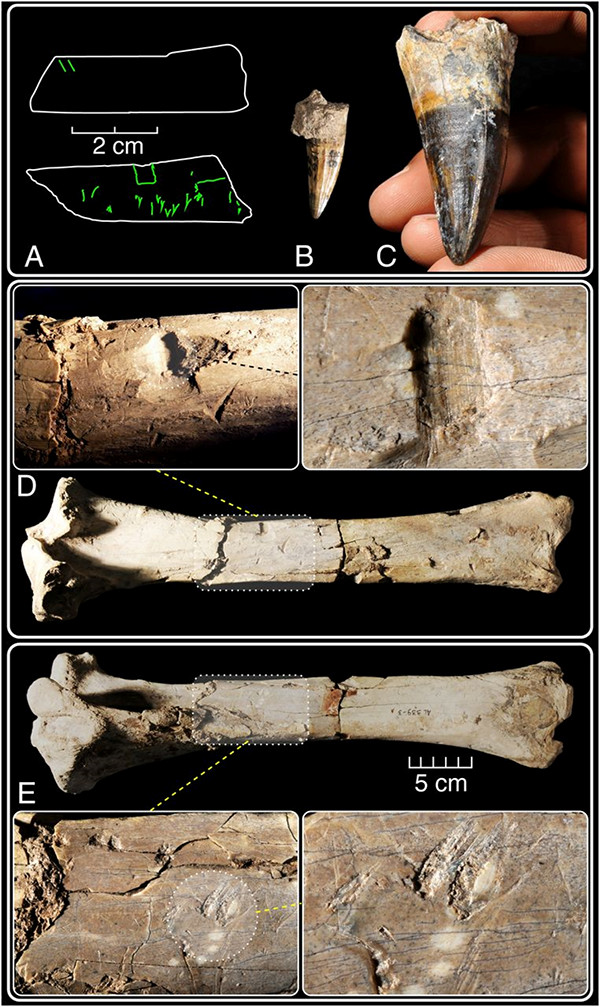

Two crocodile teeth found at the collection site along with a horse leg bone with marks that Yonatan Sahle's team studied. Credit: Y Sahle et al./PNAS 2017.

An ongoing debate regarding the origin of scrape marks on ancient animal bones has taken a new turn. The marks were first thought to have been made by early hominid butchers, then by trampling, and now it’s looking like crocodiles might have been responsible, according to a recent study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“We are trying to warn colleagues and students to be very critical of the evidence presented,” says Yonatan Sahle of the University of Tübingen in Germany, lead author of the study that reevaluated the marks on animal bones found in Ethiopia’s Afar Depression. “Our work has shown that different processes may lead to the production of similar outcomes.”

The controversy stems from the 2010 discovery of two small bones in Dikika, Ethiopia, that have been dated to 3.4 million years ago. When the scrapes on those bones were announced in Nature as hominid butchery marks in 2010, the date for the earliest stone tool use was pushed back from 2.6 million to 3.4 million years ago. That would mean that Australopithecus afarensis was the first hominid to use stone tools instead of a more modern species, as was previously thought. In 2011, Manuel Dominguez-Rodrigo of Complutense University in Spain and colleagues wrote a strongly worded rebuttal in PNAS, pointing out that the bones weren’t recovered from the same sediment layer in which they’d originally been deposited, meaning they could have been reworked. He noted that the abrasiveness of the sediment could explain random striae found on the bones that the first team did not take into account, and suggested that trampling by large animals in rough sediment likely created the combination of linear marks, V- and U-shaped grooves, and scattered striae. Dominguez-Rodrigo argued that the earliest evidence of stone tool use was still from 2.5 million to 2.6 million years ago. Several other studies in the meantime have reached different conclusions, including one in the Journal of Human Evolution in 2015 in which researchers provided further evidence in support of the butchery hypothesis.

In trying to solve this mystery, in 2017, Sahle and his colleagues traveled to Ethiopia and collected hominid and faunal fossils of the same age and depositional environment as the controversial bones collected in 2010. They evaluated these using scanning electron microscopy, photographs, confocal microscopy and bone casts. The team also butchered a sheep carcass with stone flakes to mimic early stone-tool use. They studied “carcasses from crocodile feeding experiments and found the same straight lines and V-shaped grooves” that were made by the stone flakes on the sheep carcass and found on some of their collected ancient bones, Sahle says. In other words, it appeared similar looking markings could be made in a variety of ways.

Among the bones the team reviewed were approximately 50 Australopithecus anamensis specimens. These hominids lived 4.2 million to 3.9 million years ago, preceding A. afarensis. An A. anamensis humerus bone dated to 4.2 million years ago with linear, V-shaped grooves — marks previously thought to be associated with stone tools — was within the collection. In the new paper, Sahle and his colleagues use this bone as an example to point out that the marks, studied in isolation, would lead to a stone-tool conclusion; taken in context of the anatomical, stratigraphic and sedimentological conditions, however, and many more possibilities arise. Meanwhile, evidence that the marks on the ancient bones resulted from crocodile feeding is becoming stronger. Not only did the bone markings Sahle and his team studied resemble those made by modern crocodiles, but the hominid fossils they collected came from what used to be waterside sites, and crocodile fossils were also found in the same sediment layers.

Different processes can bring about the same results, Sahle says. “There are different agents of modification in play here.” And while he says he thinks his team has succeeded in highlighting this issue, he knows there’s still a lot more to be done to understand the true origins of bone marks and their implications for human evolution. “Crocodiles have serrated teeth, different-sized teeth, and newly erupted teeth that are sharper than older teeth,” Sahle says, and experiments need to be done to fully understand marks made under different circumstances and by different means.

Stephanie Drumheller-Horton of the University of Tennessee agrees, adding that scientists need more context than bone marks alone can provide to begin recreating the early-hominid environment and determine the first occurrence of stone-tool use. “The crocs that are present in some of the sites where we have [found] early human ancestors haven’t been as [well] studied as other members of those environments,” but “they’re obviously important,” she says. “If we want to have a better idea of what these [ancient crocodiles] were doing, we need to study them, and not just their feeding traces.” To do that, Drumheller-Horton calls on the scientific community to focus on the total diversity of processes that can leave their marks.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.