by Sam Lemonick Tuesday, October 15, 2013

The S.S. Jacob Luckenbach went down off the coast of California in July 1953 and has been leaking oil for decades. It is estimated that the vessel has leaked more than 1.1 million liters of oil. California Department of Fish and Wildlife

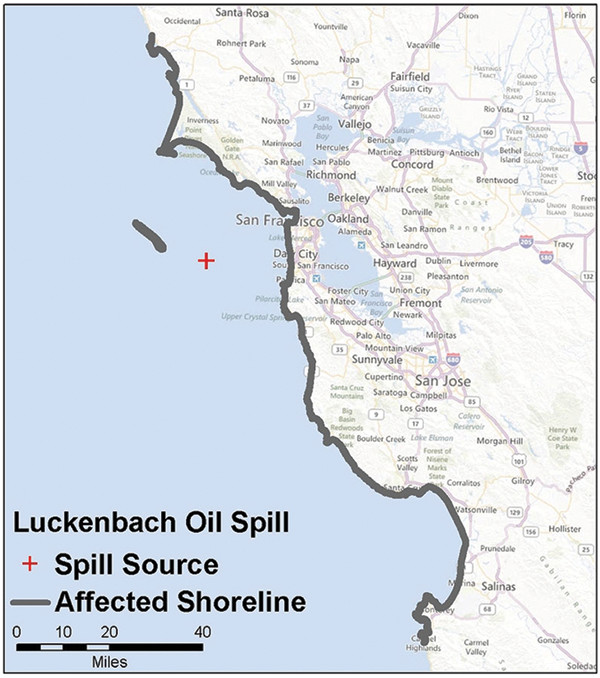

In the 1970s, mysterious oil spills began to plague hundreds of kilometers of California’s Central Coast. The spills usually occurred in winter, during large storms, and — with the exception of a few tarball events, like one that afflicted Point Reyes National Seashore in the winter of 1997-98 — little oil was seen on the beaches or in the water.

Instead, the spills were marked by the sudden appearance of oiled seabirds on beaches from Bodega Bay to Monterey Bay. Between 1990 and 2003, the mystery spills killed more than 50,000 birds, mainly Common Murres, and several sea otters. It wasn’t until 2002 that a joint effort by the U.S. Coast Guard, NOAA and the state of California finally identified the source of the oil: the S.S. Jacob Luckenbach.

In July 1953, the steel-hulled freighter had sailed out of San Francisco harbor loaded with supplies for the Korean War — including 1.7 million liters of bunker fuel. About 30 kilometers west of the Golden Gate Bridge, it collided with another ship and sank in 55 meters of water in an area that would later be designated the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. Since 2002, officials have worked to remove 322,000 liters of oil from the hulk, enough to fill 10 oil tanker trucks. It is estimated that, over the years, the vessel has leaked more than 1.1 million liters of oil.

About 20,000 shipwrecks like the Jacob Luckenbach litter U.S. waters, sunk by weather, war, collisions and other incidents. A new NOAA report identifying 87 wrecks with the highest risk of leaking oil could help direct responders to the sites that pose the most serious danger to marine and seashore environments.

NOAA began with a catalog of all U.S. shipwrecks, from which it eliminated the wrecks that pose the lowest risk. The NOAA team, led by Lisa Symons, a resource protection coordinator in NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, rejected ships powered by coal or wind, ships made of wood and other less durable materials unlikely to still contain oil, and those that sank violently and lost any onboard oil or fuel as they went down. The remaining ships mostly sank between 1941 and 1945 during World War II, before the U.S. could adequately protect Navy and Merchant Marine ships near its coasts from German and Japanese submarine attacks.

The team then pored over logbooks, ship manifests and other historical records to learn as much as they could about the vessels, their cargo and the weather conditions in which they sank. That included estimating factors like how much fuel a ship consumed before it was lost. The team also combined historical information with recent and old reports from divers and remotely operated vehicles to gauge the structural integrity of each wreck.

That process revealed 87 shipwrecks along U.S. coasts, in the Great Lakes and near islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. Using simulations from an oil spill impact model called SIMAP, the researchers then calculated the effects of leaking oil — ranging from a 100 percent leak down to a 0.01 percent leak — for each of the 87 vessels. The researchers assigned a probability of discharge to each wreck, ranging from the worst case discharge (10 percent of the oil still onboard leaking at once) to the most probable case, which entailed smaller periodic leaks. Based on these criteria, and taking into account the ecological effects of a spill on coasts and the water column, and its effect on tourism, fishing and other socioeconomic resources, the team assigned a score assessing the oil risk posed by each wreck. The highest-risk wreck is currently the Gulfstate, an oil tanker located about 80 kilometers off the southern tip of Florida.

“This is the first assessment in U.S. waters that has a historical and archaeological component, an engineering component, the pollution modeling, the ecological and socioeconomic look, so it’s the first really comprehensive look,” Symons says.

The report will help the U.S. Coast Guard and other agencies prepare for potential or existing spills from the 87 wrecks. “We knew that there were thousands of vessels out there that have sunk over the years,” says Forest Willis, incident management and preparedness advisor to the Coast Guard’s 7th District in Miami. Through computer modeling and the use of historical data, NOAA was able to “research all these vessels that we certainly don’t have the time or staff to do,” Willis says. The Coast Guard is working with local responders and community leaders to make the most of the report’s information, he says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.