by Cassandra Willyard Thursday, January 5, 2012

Oil from a century-old spill has seeped into Newtown Creek, one of the most polluted waterways in the United States. Cassandra Willyard

Cassandra Willyard

Plastic booms hold back oil seeping into Newtown Creek from the Greenpoint shoreline. Giles Ashford

Greenpoint is bordered by water on two sides - by the East River to the west and by Newtown Creek to the north. Newtown Creek separates Brooklyn from Queens. ExxonMobil

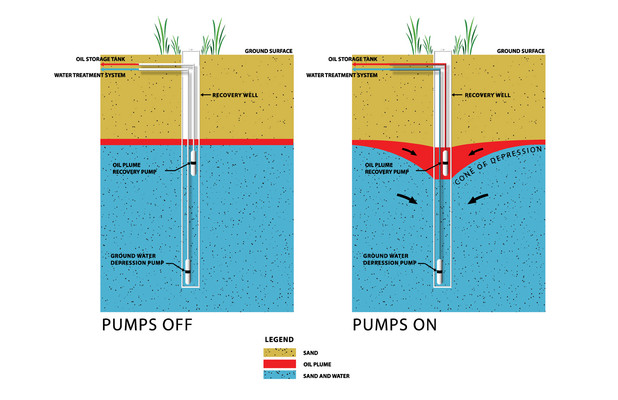

Dual-pump recovery wells work by creating a cone of depression (right). The bottom pump lowers the water table while the top pump sucks up oil. ExxonMobil

Newtown Creek flows into the East River. Cassandra Willyard

Wedged between the hard-bitten boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, N.Y., lies a six-kilometer-long slip of sickly green water called Newtown Creek. Dubbed the most polluted waterway in America, this tidal tributary of the East River has no natural headwater: The water that feeds the mostly stagnant creek is a combination of industrial wastewater, stormwater runoff and, after a hard rain, raw sewage.

When I visited the creek last March, the day was blustery and bitterly cold. My tour guides — Captain John Lipscomb and Basil Seggos of the environmental organization Riverkeeper — motored us past a desolate hodgepodge of cement factories, recycling facilities, scrap yards and barren brownfields. Rafts of garbage floated in the murky water. But I wasn’t there to see trash; I was there to see oil.

During the latter half of the 19th century, the shores of Newtown Creek boasted dozens of petroleum refineries. Although most closed down decades ago, their legacy remains. Newtown Creek’s southwest shore forms the northeast boundary of the largest oil spill in U.S. history. The plume — a toxic concoction of kerosene, fuel oil, gasoline and naptha (a key ingredient in napalm) — floats at the top of a subterranean aquifer beneath the working-class community of Greenpoint in Brooklyn.

Although the oil companies that populate the creek’s banks began cleaning up the spill nearly three decades ago, only 9.5 million of the 17 million to 30 million gallons of oil have been recovered. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that getting the rest out could take another 25 years.

The slow pace of remediation has left many residents, local officials and environmental organizations bitter. They say the oil companies could and should be doing more. “One of the huge concerns is that there’s this ginormous oil spill that is underneath the homes and the businesses of just ordinary people, really compromising their health as well as their property values,” says Kate Schmid, head of the Newtown Creek Alliance, a local community group co-founded by Riverkeeper.

Today the spill is at the center of at least five separate lawsuits — including one levied in 2007 by the state of New York — and local lawmakers are calling for the spill to be added to the nation’s list of Superfund sites.

Newtown Creek’s industrial heyday began in the 1850s. The site was a natural choice for industry: The waterway made transport easy and the land surrounding the creek wasn’t subject to New York City’s environmental rules and regulations. Newtown Creek became a haven for “all kinds of nasty industries — zinc smelting, butchering, oil refineries,” says Jack Eichenbaum, an urban geographer and New York City walking tour guide. “No one was paying attention. They could do whatever they wanted.”

By the late 1800s, the creek’s shores boasted 50 petroleum refineries, as well as a bevy of fertilizer manufacturers, chemical plants, varnish factories and glue makers. The refineries produced kerosene, which replaced whale oil as the fuel of choice for lighting homes and streets. Boat traffic on Newtown Creek rivaled traffic on the Mississippi, and the water gave off such a foul stench that the neighborhood assembled a “smelling committee” to keep tabs on the creek.

In 1892, oil magnate and entrepreneur John D. Rockefeller consolidated most of the refineries into the Standard Oil Trust. In 1911, however, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that Standard Oil was in violation of federal anti-trust laws and ordered it disbanded. The largest refinery, on the south side of the creek, which had the capacity to turn 1.4 million gallons of crude oil a day into fuel oil, gasoline, kerosene, solvents and refinery oil, became part of Standard Oil Company of New York, known as Socony. Paragon Oil Company operated a petroleum storage facility next door.

In 1966, 11 years after Socony became Mobil, the company shut down the refinery and sold off much of its property. Amoco Oil Company (now BP) purchased four hectares and constructed several storage tanks to hold diesel fuel, fuel oil, kerosene and gasoline. Mobil used the remainder of its land for storage as well.

Exactly when and where these products began seeping into the ground is unclear. Many news outlets have linked the spill to a mid-1900s sewer explosion that blew manhole covers three stories into the air and shattered hundreds of windows, but Barry Wood, a spokesperson for ExxonMobil in New York (Exxon acquired Mobil in 1998, assuming responsibility for cleaning up the majority of the spill) rejects that notion. He says the oil accumulated slowly over more than a hundred years.

Back then, oil companies did not have rigorous systems for keeping track of their product, Wood says. “I’m sure there were tank ruptures. I’m sure there were spills. I’m sure there were some fires,” he says. A 2007 EPA report states that it is ambiguous whether the spill is the result of “one or two events or the culmination of 140 years of spillage.” What is clear, however, is that no single party is to blame. All three companies — Mobil, Amoco and Paragon — likely share responsibility. The location of the plume, under all three sites, is telling. Furthermore, petroleum pulled from the offsite spill bears an uncanny resemblance to products once held by Mobil. And investigators found traces of a blue dye in the portion of the plume under Amoco’s site that was only added to Amoco Premium Unleaded gasoline.

Although no oil is leaking into the ground in Greenpoint today, the spill isn’t quite ancient history. Mobil leaked an additional 50,000 gallons into the ground as recently as 1990 when one of its storage tanks collapsed.

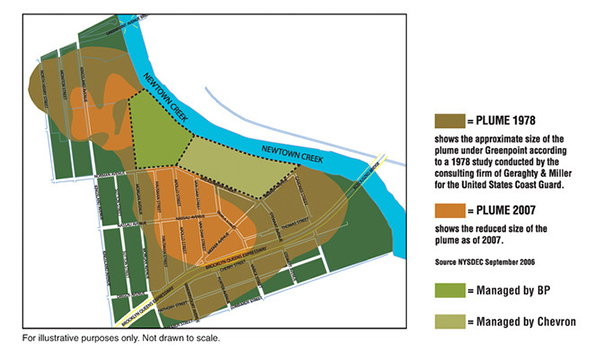

The massive spill was not uncovered until Sept. 2, 1978, when the U.S. Coast Guard noticed an oil slick on the creek during a routine flyover. The oil was seeping into the water from a metal wall in front of what had once been Paragon’s oil storage facility. A subsequent investigation revealed that the oil on the creek — some 400 gallons — was just the tip of the iceberg. A consulting firm hired by the Coast Guard found that approximately 17 million gallons of oil had percolated into the ground and pooled at the top of the aquifer, beneath approximately 12 meters of sand, silt and clay. They estimated the spill encompassed more than 20 hectares.

“The state should have stepped in when there was a big discovery of the spill and a report done by the Coast Guard,” says Basil Seggos, chief pollution investigator for Riverkeeper, based in Tarrytown, N.Y. But no one could quite figure out who should be responsible for overseeing the cleanup. The Coast Guard oversees only navigable water — rivers, lakes and the sea. “The feds decided they didn’t have any jurisdiction,” Seggos says, “because the spill was primarily affecting groundwater.”

In 1979, stakeholders from the city, the state, the American Petroleum Institute, Amoco, Mobil and Texaco (which owned Paragon and was later bought by Chevron) banded together to form the Meeker Avenue Task Force. They installed wells near the wall to catch oil before it could enter the creek.

In 1987, the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC)

took control of the project. Three years later, just after the tank

collapse on Mobil’s property, the agency met with Mobil to hash out a

cleanup agreement, called a consent order. ExxonMobil says the state

wanted to formalize the cleanup process. The state says the agreement

was mutual. Seggos speculates that disasters such as the 1989 Exxon

Valdez oil spill in Alaska made both parties “eager to get to the

table.” Whatever the impetus, Mobil agreed to clean up its own

waterfront property, the property once held by Paragon and the portion

of the plume that extends into Greenpoint’s residential area.

Schmid calls the consent orders — which contain no timeline for

cleanup and no provisions for dealing with the contaminated soil or

creek — “toothless.” At the time, she says, New York was not in a

position to play hardball with the well-funded oil companies. The

state’s coffers were empty and the government could barely stay afloat.

“The timing was awful,” Schmid says. “The Exxon attorneys went in and

whipped around the state lawyers.”

Seggos says DEC didn’t have enough political clout in the 1990s to ensure that the oil companies followed the consent orders. “[Gov. George] Pataki’s goal was to make New York a better place for business,” he says. “And the practical impact was that a case like this, which should have been more aggressively handled, was instead left to the devices of the oil companies.”

Seggos first stumbled across the spill in October 2002, when he and his colleagues decided to leave the East River and cruise up Newtown Creek. Less than two kilometers upstream, they noticed a sticky sheen. The creek “was literally coated with oil — shore to shore, hundreds of yards up and downstream, an inch to half an inch thick,” Seggos says. “It was just bleeding out of the shoreline.” A makeshift boom had been set up along the shore to catch the oil, but parts of it were submerged and the wake from passing barges had washed the oil into the creek.

Riverkeeper called DEC’s 24-hour spill hotline. But DEC, which already knew about the spill, told Riverkeeper the situation was under control. Seggos, however, did not agree. “If oil gets into a creek,” he says, “it’s already a problem because some of it dissolves and some of it sinks to the bottom.” Seggos saw the oil slick as a sign of just how “magnificently” things had fallen apart.

It took Riverkeeper more than a year to put together a lawsuit. In 2004, the organization filed notice of their intent to sue ExxonMobil. Now Riverkeeper’s lawyers — law students at the Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic who donate their time — are locked in the discovery period of the suit, gathering evidence, deposing witnesses and sifting through any and all documents, memos or studies that might be relevant to the case.

Although millions of gallons of oil have been recovered, millions of gallons remain. In 2007, EPA suggested that the spill could have originally held as much as 30 million gallons of oil. That’s almost twice the Coast Guard’s estimate and nearly three times the amount of oil that the Exxon Valdez dumped into Prince William Sound when it ran aground in 1989.

The headquarters of ExxonMobil’s cleanup operations, on Kingsland Drive in Greenpoint, is hidden from view by a concrete wall. An electronic chain-link gate keeps out curious passersby. I arrived on a rainy Thursday afternoon to meet with Barry Wood, a New Jersey native with a thick accent and a shock of silver hair. He met me at the gate, lamenting the fact that I had just missed the mandatory staff safety luncheon. “Just standing around here talking, you don’t get a sense of the magnitude of the human resources that have been applied to the project,” he said. “We’ve got 62 guys,” added Steve Trifiletti, the project manager. “We ordered pizza for 80 and we didn’t have enough.”

Wood, my tour guide for the afternoon, is a former Exxon employee who the company brought out of retirement in 2006 to do public relations. Wood sported a button-down shirt and slacks, even though ExxonMobil’s property is largely a construction site — an expanse of dirt and bulldozers ringed by a network of ash-gray trailers, oil trucks, tanks and metal sheds. We retired to a makeshift conference room inside one of the trailers. Wood wanted to show me a presentation that he had put together outlining ExxonMobil’s commitment to cleaning up the spill.

These days ExxonMobil’s recovery operation is high tech. To siphon oil from the water table, the company uses a system of “dual-pump recovery wells.” These wells (as their name implies) hold two pumps — one situated inside the oil plume and another placed several meters below in the aquifer. The bottom one sucks up vast quantities of water, creating a funnel-shaped cone of depression into which the oil pools. That allows the top pump to access more oil than it could otherwise. Wood says to imagine skimming fat off the top of a pot of chicken soup. “You stick a ladle in the middle of the pot,” he says, “and depress the soup until the fat flows in.”

The water, which is contaminated with lead, volatile solvents such as acetone and cancer-causing chemicals, goes to one of ExxonMobil’s two water treatment facilities. There it passes through a settling tank, a series of filters and an aerator designed to remove volatile organic compounds. The treated water, some 500,000 gallons each day, flows into Newtown Creek. The oil, roughly 1,500 gallons each day, is piped into holding tanks near each well and later recycled.

W. Thomas West, a vice president at the Boston-based consulting firm Haley & Aldrich, had previously worked on the ExxonMobil site in Greenpoint 15 to 20 years ago as a consultant hydrologist with a different environmental firm. At the time, Mobil had just installed dual-phase recovery pumps in a series of extraction wells. The remedial technology, he says, “was and still is state of the art for the recovery of petroleum.” According to EPA’s 2007 assessment, the dual-pump wells are working fine for now. The assessment suggests that the oil companies can clean up 70 percent of the spill using such wells. After that, however, they’ll have to turn to another technology: EPA advises the companies to investigate the feasibility of injecting hot water or steam, heating the soils or trying bioremediation.

ExxonMobil has 21 oil recovery wells, though only 11 are running in dual-pump mode. The other 10 only use the top pump to suck up oil, which is less efficient. “We have to get permits from the city to move the water,” Wood says. “Then the recovery rates will grow.” Wood hopes to have the necessary permits by the end of the year. That should boost oil recovery to 2,000 gallons a day, he says.

Once a well dries up, the workers must drill a new one. ExxonMobil has 240 monitoring wells, which help them keep track of the plume’s margins and site new wells.

“Wherever we feel we can get the highest recovery rate is where we put a new well,” Wood says. Sometimes that’s easier said than done. “If I want to put a recovery well in your backyard and you don’t want me there,” he says, “you and I have to sit down and negotiate about access rights.”

So far, ExxonMobil has pulled approximately 6 million gallons of oil out of the ground. BP, which operates a similar system on its property, has recovered an estimated 3.2 million gallons of oil. Chevron (formerly Texaco) didn’t take responsibility for the Paragon site until 2005. Since then, the companies have installed better booms to catch oil in Newtown Creek, a grout wall to block oil seeping into the creek and more recovery wells.

“A lot of progress has been made,” Wood says. “We’ve committed significant human and financial resources to get the job done. And we’ve been successful.” This year ExxonMobil plans to spend somewhere between $15 million and $20 million on cleanup.

Not everyone is impressed with ExxonMobil’s work ethic, however. On July 17, 2007, nearly 30 years after the spill was uncovered and 20 years after DEC assumed oversight, Attorney General Andrew Cuomo filed suit against ExxonMobil on behalf of DEC for violations of the Clean Water Act. Cuomo charges that the oil seeping into the creek represents unauthorized discharges and also alleges that the treated groundwater ExxonMobil is pumping into the creek still contains petroleum byproducts and other unpermitted pollutants. “ExxonMobil — the largest, most profitable oil corporation in the world — has continually refused to accept responsibility for what is one of the worst environmental disasters in the nation’s history,” Cuomo said in a press release. “This suit sends the message that even the largest corporations in the world cannot escape the consequences of their misdeeds.”

U.S. Reps. Nydia Velázquez, D-N.Y., and Anthony Weiner, D-N.Y., are calling for EPA to fully characterize the spill and to designate the area a Superfund site and have introduced legislation to that effect. “To devise an appropriate remediation system, you have to know where it is and how big it is,” Seggos says. “More science and better data are going to help tell us what needs to be done.”

The residents of Greenpoint aren’t pleased with the oil companies' efforts either. Many are concerned about their health. Although the locals are not likely to come in contact with the toxic brew beneath their feet — Newtown Creek is largely inaccessible and Brooklyn’s drinking water now comes from upstate (see sidebar) — liquids under pressure can become toxic vapors that can seep up through the soil. The process is known as vapor intrusion.

In 2005, Seggos, frustrated with the state’s inaction, decided to see for himself if the oil spill was releasing any noxious vapors. He and his colleagues dug a test hole on what used to be Paragon’s property. They found that the dirt was infused with methane and benzene, a known carcinogen.

The benzene levels did not appear to exceed any legal limits. Still, local residents were worried. Several contacted Erin Brockovich — famously played by Julia Roberts in the biographical film of the same name. In late 2005, Brockovich flew to Greenpoint with lawyers from the Los Angeles-based law firm Girardi & Keese to rally the community. “If you made a mess, you would try and clean it up, wouldn’t you?” Thomas Girardi asked the nearly 60 community members gathered at the Swinging Sixties Senior Center. “The oil companies are not good corporate citizens. Exxon is the worst of a bad bunch. Unless they get hit with a court order, they won’t do it.”

Girardi & Keese now represents 350 property owners. The firm alleges the spill represents a form of “chemical trespass.” Girardi & Keese hasn’t specified an amount for damages, but a separate law firm, which represents another 300 residents, is asking for $58 billion. If the state and Riverkeeper win their lawsuits, much of the money will go toward cleaning up the creek, Schmid says. These lawsuits ensure that the community will receive some compensation as well.

ExxonMobil maintains that the spill is not a health risk. “You have nobody breathing it, nobody drinking it and nobody touching it,” Wood says, “so we feel very confident that no one has been exposed.”

And so far, no plume-related vapors have been found in Greenpoint’s residential areas. The New York State Department of Health (DOH) and DEC jointly tested the air inside 52 homes in 2006 and 2007. They found no evidence of plume-related vapors in any of the houses and “the levels of chemicals in the outdoor air were similar to other areas of the city,” says Claire Pospisil, a DOH spokesperson.

But that doesn’t mean that vapor is not a concern. ExxonMobil began monitoring benzene and methane in the soil a few years ago. Although they found nothing of concern in residential areas, they did find elevated levels in the commercial district, near where Seggos had dug. In at least one spot, benzene vapors were 2,000 times the soil gas guidelines set by EPA (though the guidelines do not represent legal limits). In fact, benzene exceeded EPA guidelines at 11 of the 25 measurement sites. ExxonMobil has since installed a vapor extraction system, which is basically a large vacuum that sucks the vapors into an incinerator. “It’s just a responsible thing to do,” Wood says. According to Pospisil, the state will also continue to monitor vapors.

The vapor intrusion should not have been a surprise, Seggos says. In 1996, a coffee roasting company called Eldorado, Ltd., considered setting up a roasting plant on an industrial lot above the spill on Apollo Street. The company sent a consulting firm to assess the site. The firm found that benzene levels inside the existing buildings were 16 to 42 times the exposure limit set by the Occupational Safety & Health Administration — 160 to 400 times the limit recommended by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Eldorado decided not to purchase the property.

Despite spending more than an hour on top of the spill and two hours on Newtown Creek, I never saw any sign of Greenpoint’s oily sludge. The booms that hold back the oil that oozes out of the creek’s shoreline were blocked by police and rescue boats the day I visited. Officials were searching for the body of a man who had driven his Mercedes-Benz into the creek a few hours before sunrise. The muddy water, which smelled vaguely of metal and rotten eggs, was filled with rescue divers. I didn’t envy their search.

But not everyone has to see to believe. Sometimes hearing is enough. Seggos and I had met that morning at the Ash Box Café on Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint. A woman sipping coffee at a nearby table overheard us talking about the spill. As we were leaving, she pulled Seggos aside. “Are we all going to die because we live here?” she asked with a half-hearted grin.

Seggos smiled reassuringly. “The problem is no different from anywhere else in the city,” he told her. But later, back on the boat, he was sober. “It’s what you can’t see that troubles you.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.