by Nick Luchetti Friday, April 12, 2013

Tornado in Kansas in 2008. NOAA

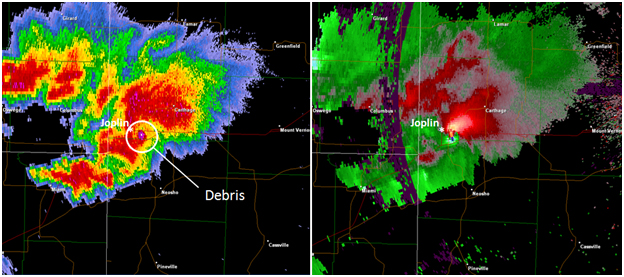

Radar reflectivity and storm relative velocity maps show the severity of the tornado that hit Joplin, Mo., in 2011, killing 158 people. NOAA

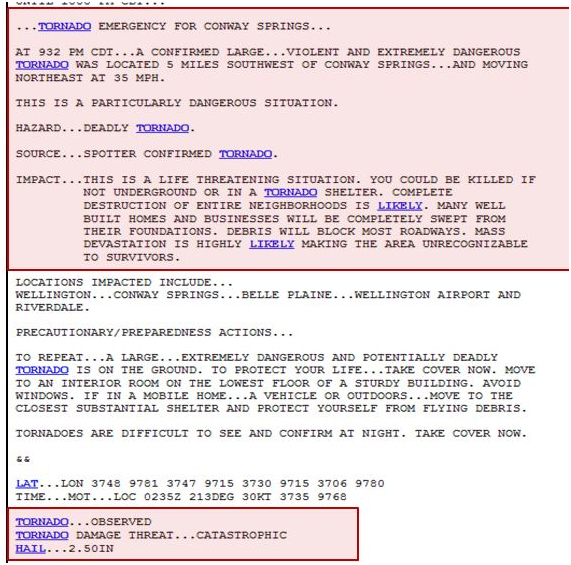

This tornado warning was issued in 2012 as a potentially catastrophic tornado bore down on Conway Springs, Kan. NOAA

Damage from the Joplin tornado. The new tornado warnings are aimed at helping avoid loss of human life. Little to nothing can be done to prevent property damage in the face of a catastrophic tornado. NOAA

On May 22, 2011, a column of rotating air spawned a massive EF-5 tornado, with wind speeds greater than 200 miles per hour, over the city of Joplin, Mo. The twister caught the city off guard, leaving 158 people dead and injuring more than 1,000 people, making it the deadliest tornado in the United States since record-keeping began in 1950. As the National Weather Service (NWS) surveyed the city following the tornado, they began considering ideas on how to better alert the public to the risks of dangerous weather events. After a successful test phase of one such idea, the agency is now expanding on its so-called “Impact Based Warnings” experiment.

The experiment began in April 2012 when five weather stations in Missouri and Kansas began including new descriptive language in their tornado warnings. Tornado service assessments have found that people tend to await confirmation that a tornado is touching the ground before seeking shelter, says Jim Keeney, weather program manager for the Central Region of the NWS and director of the new experiment. “We wanted to put more information into our tornado warnings to help [people] make quicker decisions.”

Along with the new wording, tornado threat tags will be attached to the warnings based on the severity of the situation. If weather radar indicates possible tornado rotation, for example, the warning message will include the words “radar indicated” followed by the potential damage threats.

If there is confirmed evidence of a large tornado on the ground capable of producing significant damage and expected to be long-lived, the warning will state that “this is a particularly dangerous situation,” along with details about the “considerable” damage potential and the urgency to seek cover.

For extremely dangerous tornadoes that pose an imminent or ongoing severe threat to human life and are capable of disastrous damage, the NWS will issue a “tornado emergency,” vividly explaining the likely devastation, urging those in the path to seek immediate shelter underground or in a tornado shelter or face unsurvivable conditions. These warnings are for “catastrophic” tornadoes, those likely to cause “complete destruction of neighborhoods,” including “many well built homes and businesses,” according to NWS. Such distinctions are rare, however, primarily because it’s often difficult to determine the severity of a tornado until after the event.

“The threat tags were mainly created for media and emergency crews,” Keeney says, adding that civilians tend to rely most on the media and emergency crews for confirmation that there is indeed a tornado in the vicinity. “We wanted to focus on these emergency outlets first,” he says.

The system was set to be tested in five locations last year, but the lack of tornadoes in those locations in 2012 limited the opportunities to just one event — in south-central Kansas on April 14. An outbreak spawned 24 tornadoes across Kansas on that day, including a strong tornado that damaged parts of Haysville, Oaklawn and Witchita. Following that event, a private verification group working for the NWS conducted interviews and focus groups with media and emergency crews, as well as local forecasters, to gauge its impact. Keeney says the groups reported that the new language was very useful and was vital in preventing fatalities that day.

This year, starting April 1, the NWS expanded the experiment to 38 weather stations throughout 12 additional states within the Central Region. “After the next two severe weather seasons, we will make any necessary tweaks to the project, push it to [NWS’s] national headquarters, and see if they want to make it operational for the rest of the country,” Keeney says.

Despite positive feedback from the initial experiments, there may be potential negative consequences from using such intense language as well.

The warnings are a “sound idea,” says Dave Carroll, a meteorologist and tornado researcher at Virginia Tech, especially if social scientists find that enhanced wording has the desired effect of prompting the general public to action. But there is also the threat of the warnings' effectiveness succumbing to the “cry wolf syndrome,” Carroll says. “If particularly strong language is used in the warning and then the expected weather does not impact the warned area, or [the event] turns out to be significantly weaker than anticipated, forecasters may risk losing public confidence even more,” he says.

Beyond changing the language of forecasts and warnings, Carroll adds, “significant improvement in the public response must be tied to education and awareness.” It is important to impress upon the public that the atmosphere is complex and that the weather rarely unfolds exactly as forecasted, he says.

As volatile and violent weather events like the Joplin tornado, the Tuscaloosa tornado outbreak on April 27, 2011, or Superstorm Sandy continue to impact the U.S., management agencies will face the same dilemma time and again: How do they spur people to react to potentially dangerous weather without overhyping the threat? “With more information added to our warnings,” Keeney says, “our hope is that it will ring the bell louder and get people to make a quicker decision to seek shelter.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.