by Julie Freydlin Wednesday, June 12, 2013

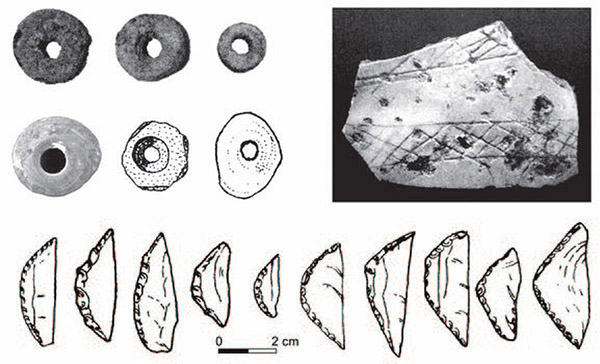

Stone tools and artifacts dated to 40,000 to 50,000 years ago from South Asia (shown) resemble slightly older finds in South and East Africa. Illustrations by Dora Kemp, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge University

Figuring out when modern humans left Africa and migrated throughout the world is a complicated task. For example, some evidence suggests modern humans may have migrated out of Africa and into Asia as early as 120,000 years ago. Further evidence puts modern humans in India and other parts of South Asia prior to the super-eruption of Mount Toba in Sumatra, which took place 74,000 years ago. However, new research suggests that modern humans may not have reached South Asia until well after the Toba eruption.

In a study published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Paul Mellars, a professor of prehistory and human evolution at the University of Cambridge in England, and his colleagues analyzed archaeological information from previous studies and information from genetic databases to show that modern humans left Africa about 60,000 years ago and arrived in India between 55,000 and 50,000 years ago.

To obtain genetic information, the group analyzed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) obtained from individuals living in India and compared it to mtDNA from individuals living in Africa, Arabia and China. This analysis showed that the people who dispersed from eastern Africa to Asia all belonged to the same haplogroup — a group of people with the same ancestor. This haplogroup, called L3, originated in Africa about 70,000 years ago. Shortly after leaving Africa, the L3 haplogroup split into M, N and R haplogroups. It is these haplogroups that scientists find in India, not the L3 haplogroup.

“It was probably in the course of crossing southern Arabia that the M, N and R lineages emerged — that is, diverged — from the parent L3 haplogroup,” Mellars says. These haplogroups are dated to 65,000 to 60,000 years ago at the earliest, he says, which means that modern humans could not have arrived in South Asia prior to this time.

The archaeological evidence Mellars and his team relied on consisted of microlithic, or blade-like, tools found in South Asia, which date to about 40,000 years ago, but possibly as far back as 50,000 years ago. Mellars and his colleagues suggest that when modern humans left Africa 60,000 years ago, they took the tools with them, which is why the tools appeared in South Asia a few thousand years later. “These early microlithic technologies are absolutely identical to the technologies you find in East Africa,” Mellars says. “They are so similar, it can’t be accidental.” In addition, the team reported, other artifacts such as circular beads and fragments of red ochre and ostrich eggshell with a crisscross design first appear in Africa and then in Asia — at the same time that genetic evidence shows that the migration happened.

Not everyone agrees with the team’s conclusions, however. Michael Petraglia, an archaeologist at University of Oxford in England, has studied a different set of stone tools found in India in stratigraphic layers above and below the ash layer from the Toba eruption. The tools his team has found below the ash layer (older than the eruption) are similar to the stone tools above the ash (younger than the eruption). Petraglia says that the same type of hominids — modern humans — must have made the tools found above and below the ash, which means that modern humans were present in India prior to the volcano eruption.

In addition, Petraglia says, genetic studies of the remains of ancient aboriginal hair place the migration anywhere from 62,000 years ago to 75,000 years ago, and other studies also suggest that mitochondrial DNA clocks might need revision in the way they are calculated.

“Our team is currently conducting archaeological field work in Arabia, India and Sri Lanka. We expect that significant new findings will emerge in the next few years that will show that the out-of-Africa story is complex,” Petraglia says. “What we can agree on is that little research in these key geographic regions has been conducted and much more evidence needs to be collected to support or refute the different theories.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.