by Mary Caperton Morton Tuesday, December 27, 2016

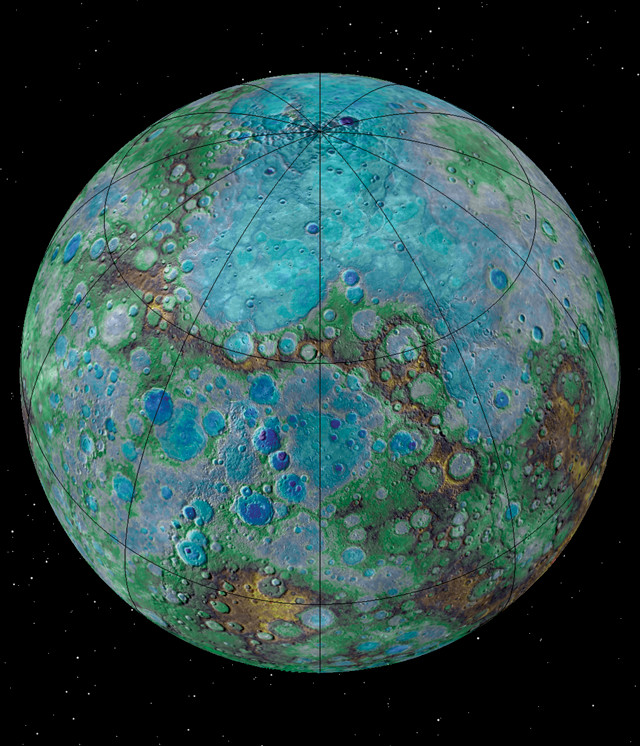

The MESSENGER spacecraft orbited Mercury for four years, producing high-resolution images of the planet's surface. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington/USGS/Arizona State University.

Not so long ago, Mercury was the least-studied planet in the inner solar system, known only from Earth-based observations and from Mariner 10’s brief flyby in the 1970s. In 2011, the MESSENGER spacecraft began orbiting Mercury, imaging the planet’s crater- and fault-scarred surface before crashing into it, as planned, in 2015. As MESSENGER spiraled downward, it took a last series of high-resolution images, analyses of which are revealing new information about the planet’s surface geology, including evidence for recent tectonic activity.

Mercury has faults, but it does not have multiple tectonic plates like Earth. Instead, the planet has one giant plate that makes up the entire lithosphere. Mercury’s largest fault scarps are formed by thrust faults and are called lobate scarps. The largest is 1,000 kilometers long and more than 3 kilometers high. “These scarps are huge compared to anything we see on the moon,” says Thomas Watters, a planetary geologist at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and a member of the MESSENGER science team.

The hard-to-miss faults were originally imaged by Mariner 10, but Watters, lead author of a new study in Nature Geoscience detailing findings from MESSENGER’s last efforts, was curious to see if the lower-altitude images would reveal smaller — possibly younger — scarps as well. Once MESSENGER got low enough to collect the very high-resolution images needed to look for smaller scarps, “sure enough, there they were,” he says.

The small scarps are interesting because they are indeed much younger — likely formed within the last 50 million years — than the large lobate scarps, which are roughly 3.6 billion years old, Watters says. The age of the smaller scarps was determined in the new study by examining small impact craters that crosscut the scarps and erode at expected rates due to constant meteoroid bombardment. These scarps represent the first evidence for recent, and likely ongoing, tectonic activity on Mercury, Watters and his colleagues suggested. “In terms of planetary geology, 50 million years is brand new,” adds Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University who was not involved in the new study.

On Mercury, tectonic landforms, such as fault scarps, form through planetary contraction. Mercury’s interior shrank as it cooled, and the outer silicate shell was forced to contract to accommodate the change in interior volume.

“In my opinion, these very young small scarps are the smoking gun that Mercury is still contracting,” Watters says. The small faults also provide a snapshot of how the larger faults were formed, he says. “Faults start out in series or clusters and with enough contraction they merge together into longer faults that can eventually form megafaults,” he says, such as the Enterprise Rupes, a lobate fault scarp on Mercury as long as California’s San Andreas Fault.

Current tectonic activity in the form of contraction and faulting, along with recent evidence of a long-lived magnetic field, suggests that Mercury didn’t follow the expected path of thermal evolution of a small planet — its interior did not cool rapidly, Watters says. “These discoveries from MESSENGER’s last days in orbit indicate that Mercury has cooled much more slowly than previously thought,” he says. “The next step will be to use the wealth of data MESSENGER accumulated to determine how Mercury and other small rocky planets sustain their internal heat for billions of years.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.