by Brian Fisher Johnson Thursday, January 5, 2012

Digital Vision

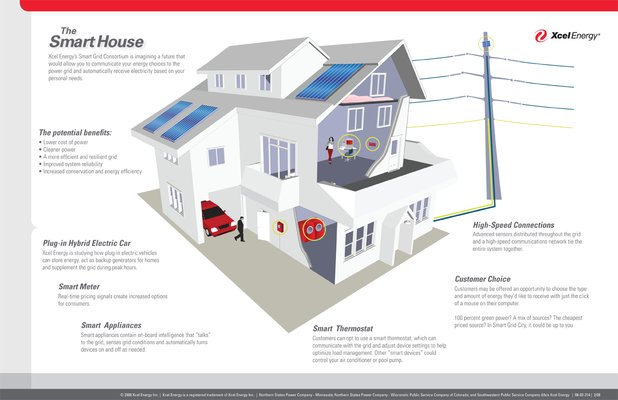

The Smart House: Xcel Energy's Smart House would include a smart meter, applicances, thermostat, high-speed connections and a plug-in for a hybrid electric car. Xcel Energy

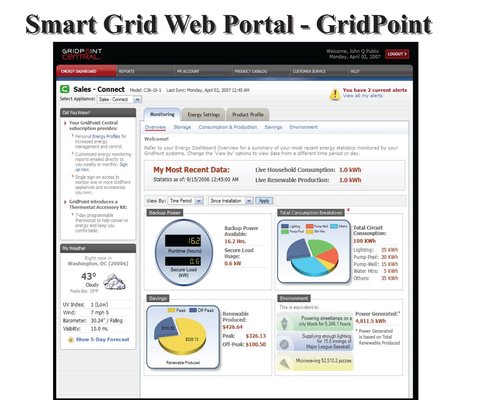

SmartGridCity customers can view energy savings, calculate hours of backup power and adjust temperature settings online. Xcel Energy

Plug-in electric hybrids can add energy back to the grid by storing energy during braking. Xcel Energy

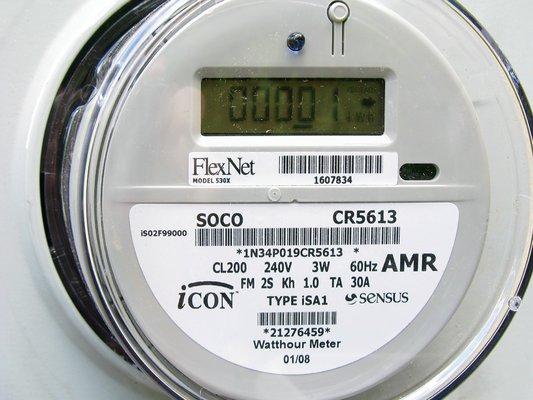

Smart meters allow power companies and consumers to better monitor electrical usage. Adrian Pritchett

General Electric advertised its involvement in smart grid technology during the Superbowl, with a take-off on 'If I Only Had a Brain' from 'The Wizard of Oz.' GE

Val and Bud Peterson are passionate about saving electricity — a seemingly hard thing to pull off given their lifestyle. The couple lives in a 650-square-meter (7,000-square-foot) two-story house in the mountains, provided by Bud’s job as chancellor of the University of Colorado at Boulder. They regularly entertain. But to save energy, Val and Bud don’t subject their guests to a low-set thermostat. And they don’t freeze themselves once the party’s over. In fact, they’re as comfortably warm as ever — yet, recently, their electric bill decreased.

That’s because their house is part of “SmartGridCity,” the nation’s first fully integrated smart grid system, organized by Xcel Energy of Minneapolis, Minn. The company is working with green technology investors to outfit about 45,000 houses in Boulder with smart grid technology. The Petersons volunteered for all the bells and whistles of the program. “I like to tell people that we have donated our bodies to science,” Val says.

And though consumers like the Petersons feel good about their savings, they’re getting a lot of help from power companies with vested interests in increasing reliability, improving service and saving money. And with more investment in smart grid technology now than ever, experts say that not even the economic crisis can slow smart grids down.

On Aug. 14, 2003, at 4:13 in the afternoon, a gaping portion of the American Northeast turned off. From Cleveland to Toronto, from Detroit to New York City, power outages darkened the region. In New York City, subway trains and elevators stopped mid-ride. Traffic signals went blank. Workers and residents crowded the streets in sweltering heat to escape from their no longer air-conditioned buildings. With no way home, thousands trekked across the Brooklyn Bridge by foot, while ferries hauled commuters across the Hudson. Fifty million people lost power in Canada and the United States. Although power was restored throughout much of the region within days, the outage caused $6 billion in economic losses, according to estimates by the Department of Energy.

After much finger pointing among officials, a U.S.-Canadian Power System Outage Task Force concluded in 2004 that the outage stemmed largely from — in addition to mismanagement by an Ohio power company — overgrown trees that had come into contact with power lines.

Power companies can avoid some such catastrophes by keeping vegetation around their lines more closely trimmed. But there’s a more fundamental issue at hand, says Steve Hauser, vice president for strategy at GridPoint, a green technology company based in Arlington, Va., which is providing some of the technology for SmartGridCity. Trees will inevitably get in the way, he says, but grid systems don’t have to be so vulnerable. “Part of the reason for that blackout was that we were running the system at or near full [capacity],” Hauser says. On a hot August afternoon, human activity coupled with air conditioning meant the grid had little breathing room. “If a power plant goes out,” he says, “it’s much more difficult for the system to recover.”

Dealing with that demand won’t get any easier. Across the nation, electricity consumption is going up. A 2007 report by the California Energy Commission, for example, found that electricity demand in that state will increase 1.4 percent per year between 2008 and 2016. Peak demand — during a hot August day, for example — will increase 1.4 percent per year between 2008 and 2013 and 1.3 percent between 2013 and 2018. That might not sound like an impressive trend, but it adds up: The 2009 Annual Energy Outlook by the Department of Energy calculates that national electricity consumption will increase at a comparable rate of 1.0 percent per year between 2007 and 2030. Over that 23-year period, that equals a demand increase of 26 percent.

Building more power plants could create the additional electrical capacity needed for peak hours. But that costs money and has political, social and environmental complications. Energy-saving appliances can play a significant role in cutting demand. For example, if every household replaced one traditional light bulb with a fluorescent bulb approved by the Department of Energy-Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program, it would “save enough energy to light more than 3 million homes for a year,” according to the program’s Web site.

“But that in and of itself only gets you so far,” Hauser says. “You could be getting twice that far or three times that far” with smart grid technology.

That’s because the current electric grid system is inefficient. Electricity delivery is a one-way path. Power companies send electricity out into the grid without any idea of whether consumers need it at that particular moment. And for a large portion of the time, they don’t. In fact, on average, Hauser says, Americans use the nation’s full electrical production capacity only about half the time, so often power plants remain off or idle, simply waiting for peak demand.

Smart grid systems, however, use information technology to help avoid that waste, telling companies via advanced transformers and meters when they can reduce electricity supply to certain households because demand is low, or even when to borrow electricity from those households because demand in other areas is high. Either way, the active choices of “smart” power providers and consumers mean that consumer lifestyles need not change.

The smart grid technology in Bud and Val Peterson’s house allows the couple to use energy when it’s needed, save it for later when it’s not, use it to charge their car, or even send it back to the energy company.

In the house, the Petersons have several programming options that save energy. Instead of heating the whole house when she wakes up, Val programs her home office thermostat for warm temperatures in the morning, and the thermostats in the bedroom, TV room and hallway for cooler temperatures. Come nighttime, Val and Bud’s smart grid system shifts the heat upstairs. Hosting a party and the great room is too hot? Take the thermostat down a notch; the smart grid knows to turn it back up the next cycle. Going on vacation? Switch the temperature settings from “summer” or “winter” mode to “vacation” with one click. And because the technology of the smart grid allows the Petersons to control everything from a Web account, they can change their settings from anywhere in the world.

“Say my husband and I go off in the winter to Australia,” Val says. “As we fly back into Denver International Airport, my husband … can actually ‘call up’ our house and as we are leaving the airport, take it from vacation mode to winter mode, and our house can be toasty warm by the time we make the 45-minute drive from the airport in Denver to Boulder.”

The Petersons’ temperature juggling act is only one aspect of their smart grid system. Two photovoltaic panels on the south side of their Spanish-tile roof can produce 6 kilowatts of solar radiation. An “inverter” translates the direct current from the solar panels to alternating current, which gets used directly or stored in lithium ion batteries in the Petersons’ old boiler room. If a snowstorm takes out the electricity in Boulder, the batteries provide up to two days of backup power for four circuits the Petersons have designated as essential: Bud’s computer, Val’s computer, the refrigerator and the security system.

Xcel has also given the Petersons a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, which, in addition to getting 54 miles to the gallon, actually builds up energy in its own lithium ion batteries from braking. The Petersons can then transfer the energy to their battery storage at home — or even sell it back to Xcel when it’s needed elsewhere in the grid. In short, the grid is no longer one-way, it’s two-way.

The Petersons’ electric bill is paid for by the University of Colorado, so Val doesn’t know exactly how much money she and Bud have saved over the course of the program. But money is not the whole point, says Dennis Arfmann, who also volunteered his house for SmartGridCity. Arfmann is an environmental lawyer whose primary interest is reducing carbon emissions. “It wasn’t so much the cost,” he says. “It was, ‘Where am I using all these watts?’”

The Arfmanns do not have a plug-in electric hybrid or lithium battery storage like the Petersons. Instead, they have a “smart” meter that tracks electrical consumption in the house every 15 minutes, along with tracking their heating, ventilation and air-conditioning circuit and the circuit that powers their dryer. Now their electric bill reads like an itemized grocery receipt.

Seeing a detailed account of their electricity use was enough to spur the Arfmanns to action. When they found out that their dryer consumed a considerable portion of their electric bill, they decided to begin drying their clothes on a line. A plug-in meter also allowed Dennis to measure the energy usage of different appliances around the house. Those readings convinced the Arfmanns to replace all of their incandescent bulbs with fluorescent ones, update their kitchen appliances with Energy Star-qualified appliances and unplug an extra freezer they had in the garage. They also now turn off or unplug energy-chugging appliances like their computer and big screen TV when not directly in use. Dennis says he and his wife have reduced their electricity consumption from about 7,000 kilowatt-hours per year to about 4,000.

And with the help of solar panels on their roof that provide real-time power to the house, the Arfmanns even produce an extra 1,000 kilowatt-hours each year that they can sell back to the grid. They made about $38 last year. “We made a few changes — not drastic changes — and found out we could shave off a third to a half of our kilowatt-hours, and Xcel will send me a check!” Arfmann says.

For Val Peterson, the drive to save energy plays into her competitive streak, she says. “People say, ‘Oh, I heard you have a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle. Well, I have a hybrid.’ And I say, ‘Does your hybrid sell energy back to the grid?’ Other people will say, ‘I have solar panels.’ And I’ll say, ‘Do yours power your cars?’ I always win. I love it.”

Research suggests that Dennis Arfmann’s conscience and Val Peterson’s competitiveness are worth taking advantage of. A 2007 study in the journal Psychological Science, for example, found that when 290 residents of San Marcos, Calif., were informed of their energy usage compared to a neighborhood average, above-average consumers decreased their usage significantly. The study also found that adding a smiley face to below-average bills helped prevent those users from lapsing into a closer-to-average consumption level. Hauser says GridPoint plans to add a similar feature to its platform.

The Petersons, the Arfmanns and likely many other households across Boulder are pleased with their energy savings. The town’s reputation for environmentalism was one of the reasons Xcel chose Boulder for the SmartGridCity program, says Tom Henley, a company spokesperson. But Henley makes no pretense about it: Xcel is looking to save money.

Colorado’s total electricity load demand is growing 2 percent per year while its peak demand is growing 2.2 percent per year, according to a 2007 report by the California Public Utilities Commission. New power plants can meet all that new demand, but that’s not necessarily a good solution. That’s where smart grids come in, Henley says. “When you start looking at the overall costs of what’s going to be needed in the future in new electrical generation, whether it be coal or natural gas, versus potential investment in updating the electric grid with technology, the cost-benefit analysis seems to make sense to us.”

At the same time, power companies face looming pressure from state governments to adopt more renewable energy in their portfolios. Colorado has called on companies to draw 20 percent of their capacity from renewables by 2020. At least 29 other states have adopted similar renewable portfolio standards. President Barack Obama’s “New Energy for America” plan (yet to be passed) would call for 10 percent of the nation’s electricity to come from renewables by 2012, and 25 percent by 2025.

Lack of transmission lines to regions with high wind, sun or geothermal potential has been a major roadblock to expanding the country’s use of renewables. But that’s only half of the challenge, Hauser says. “The problem with renewables is that you’ve got to get it from where it’s generated to where it’s used, and you’ve got to get it from when it’s generated to when it’s used.”

The sun doesn’t always shine. The wind doesn’t always blow. And although lithium ion batteries like the Petersons’ have improved the storage capabilities of renewable energy, Hauser says the intermittency of wind and solar will become a growing issue as they make up a larger portion of our electrical capacity.

“Today renewables makes up a few percent of most utilities’ operation,” he says. “When it’s a small part of the load, it’s lost in the noise. The [utility] operators can’t really notice there’s wind or solar out there on the system. But when you get around 10 percent or 15 percent, it starts to really cause operation problems,” he adds. A smart grid would help smooth over that problem, so when the winds are calm, operators could rely more on stable sources like coal, or take energy from the consumer end of the grid.

At the same time, companies could reduce demand during peak hours by encouraging consumers to cut back on usage, says Don von Dollen of the Electric Power Research Institute, who manages IntelliGrid, the institute’s research program on smart grids. “It opens the door to being able to send … price signals to customers that say, ‘Now is an expensive time for using electricity,’ as opposed to ‘Now is an inexpensive time,’ so you can shape the load curve throughout the day.” Under GridPoint’s platform, utility companies could even shut down certain appliances at peak load based on historical data of consumer aggregate usage habits. (Consumers would get to approve or override such moves.) Henley says Xcel hopes to eventually introduce both these features into SmartGridCity.

And if for some reason a tree does knock out power, Henley says smart meters would give companies an instant rundown of where service is needed. “In the past we had to rely on our customers to call us and say, ‘You know what, my power is out,’ and then we’d have to use predictive modeling to say, ‘O.K., there’s X number of calls in this area, so we need to send a truck out and see what’s going on.’ Now we’ll know immediately what’s going on out there in transformer A and transformer B, what the problem is for the most part, and be able to send our crews out there,” he says.

With the help of her lithium ion batteries as backup power, Val Peterson says a few power outages have even escaped her notice. “It goes out, they fix it, and I don’t even pick up the phone.”

All these smart meters, solar panels, lithium ion batteries and plug-in electric hybrid vehicles sound expensive — and they are. The 45,000 homes in SmartGridCity alone have cost $100 million — about $2,200 per household. Still, Hauser says power companies will be willing to foot most of the bill for upgrading their grids with smart technology because the savings from smart electricity use will more than cover their investments.

Governments are also taking interest. The federal stimulus package passed in February allocates $11 billion for smart grid investments, including five demonstration projects similar to the SmartGridCity, Hauser says. Last September, the California Public Utilities Commission approved power company Southern California Edison’s $1.63 billion plan to install smart meters in 5.3 million homes and small businesses between 2009 and 2012. And although Henley is quick to point out that smart meters on a “dumb grid” will only give companies the ability to know when their customers are out of power, von Dollen calls such initiatives a fundamental building block. “It’s one of those key things that you’re really going to need as you start deploying a smart grid,” he says.

But even though billions have already been invested in smart grid technology, it should only be the beginning of government funding, says Ahmad Faruqui of the economic consulting firm Brattle Group. The stimulus package, he says, “is not as large as people would think. It was supposed to be $11 billion for the smart grid, but a good chunk of that has already been allocated to a couple of regions in the U.S. served by public power or municipalities. The amount remaining for all the other utilities is about $4.5 billion. That’s not a lot of money for 142 million customers.” Without more financial backing, Faruqui says, a national smart grid could lose momentum, creating an awkward “quilt work” of different smart grids.

And, Faruqui warns, even after the infrastructure is updated, power companies will still continue to need help from states and the federal government. “As consumers become smart consumers, they buy less power. That means less cost — but it also means less revenue.” Transmission and distribution systems have fixed costs for utilities no matter how much customers buy, so energy savings would cut into the profits needed to cover those costs. To keep power companies afloat and profitable, Faruqui says that regulatory agencies will need to allow companies to charge a little extra.

Still, investors are buying into smart grids despite the souring economy. Venture-capital firms invested $183 million in smart grid companies during the second half of 2008, “as much as the previous four years combined,” USA Today reported in January. The same article pointed out that, “While a solar-panel factory costs about $300 million, a venture capitalist can take a big stake in a smart-grid technology company for only $50 million. And capital expenses are more than recouped through cuts in electric bills, avoiding new power plants.” Even Google is getting involved: In 2008, the company announced a partnership with General Electric to develop ecologically friendly initiatives, including smart meters and other smart grid technology. It’s a start, von Dollen says.

In the meantime, consumers like Val and Bud Peterson and Dennis Arfmann are relishing their energy savings.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.