by Kate S. Zalzal Wednesday, May 17, 2017

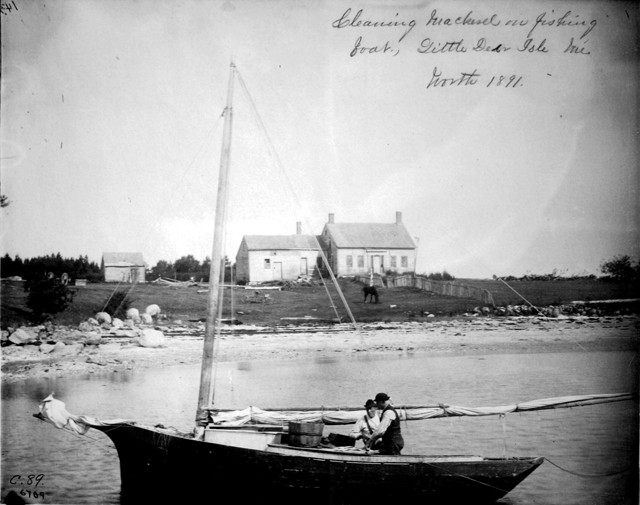

Fishermen clean mackerel near their saltwater farm on Deer Isle in Maine's Penobscot Bay in 1891. Mackerel fishing increased following the 1815 eruption of Tambora. Credit: NOAA Library, Silver Spring, Md.

The 1815 eruption of Indonesia’s Tambora Volcano led to a 1- to 1.5-degree-Celsius drop in the average global temperature, prompting 1816 to be called the “year without a summer.” New research analyzes weather data and historical records from New England to explain why, in the northeast U.S., 1816 was also called the “mackerel year.” As eruption-induced extreme weather triggered food scarcity in some areas, including a reduction in alewife numbers along the U.S. Atlantic coast, fishermen in the Gulf of Maine turned to mackerel fisheries farther offshore that had been neglected while more easily fished coastal and freshwater species were available.

Alewives — which live mostly at sea but breed in freshwater — fed both people and livestock in New England at the time of Tambora’s eruption. The fish typically arrived earlier than mackerel, herring and shad to the Gulf of Maine, and were caught with fixed fishing gear, like nets and weirs, as they made their spawning runs. But migration timing and spawning success of freshwater and saltwater fish are affected by water temperature.

In a study in Science Advances, Karen Alexander, a research fellow at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and her colleagues looked at fish export records along with meteorological data and sociopolitical influences. Alexander and her team found that alewife runs appear to have faltered in 1816, likely because cooler temperatures and extreme weather brought about by Tambora reduced the spawning success of alewives. The conditions may have also negatively impacted crops and livestock, leading to heightened fishing pressure on the fish for local consumption as well as for export.

As a result of the climatic events, “people couldn’t catch enough alewives to meet their needs, so they quickly turned to mackerel, the next most abundant species to arrive along the coast,” Alexander said in a statement. “Pursuing mackerel and rapidly distributing it to communities with no other sources of food fundamentally altered the infrastructure of coastal fisheries,” she said.

Even after Tambora’s effects dissipated, mackerel remained a dominant food source and export in the region, a consequence of fishermen adapting to offshore fishing, the researchers wrote. Although not the sole cause, Tambora’s eruption triggered changes that were ultimately transformative.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.