by Zahra Hirji Thursday, August 7, 2014

Earth’s largest active volcano is taking a nap. And after 30 years, no one is quite sure when Hawaii’s Mauna Loa will reawaken. Odds are that it will be within the next couple of decades — and that it will be spectacular.

Red hot lava will fountain violently, reaching 50 meters into the air. An underground molten magma ocean will be unleashed, draining from giant fresh cracks in the surface. A plume of sulfur-rich steam and ash will climb into the sky, billowing like a huge smoke stack.

It paints a hellish scene, but is there any danger for humans? That depends on whether the eruptions are confined to the mountain’s highest levels above the tree line, or if, as scientists and emergency managers fear, the flows and plumes migrate downslope to the realm of people and commerce.

When Mauna Loa last erupted in 1984 (left), lava came within 7 kilometers of Hilo (right). Parts of Hilo are built on lava from eruptions that occurred over the past couple of hundred years. Credit: left: U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory/ESW Image Bank; right: ©Ken Lund, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

History warns us that Mauna Loa’s current silence is anomalous. Over the past 3,000 years, the geologic record testifies that the volcano has, on average, erupted every six years. And about 45 percent of historical eruption sites have departed the volcano’s summit for lower elevations.

Lying at the foot of the mountain’s northeastern side is the Big Island’s largest city, Hilo. Despite being the population most recently threatened by Mauna Loa (when the volcano last erupted in 1984), Hilo residents are largely apathetic to their risk, according to Frank Trusdell, a geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (HVO) and the world’s leading Mauna Loa expert. Part of the problem is the city’s growing population, which has increased by almost a third since the last eruption, from about 35,000 to more than 43,000. In response, development has pushed farther up Mauna Loa’s slopes.

Mauna Loa lava flows can be seen on the Big Island, including crossing the major highways 11 and 190. The dark lava flow shown at left in this photo formed in 1859 and the dark flow shown at right is from about 1800. Credit: USDA Forest Service.

The last Mauna Loa eruption to threaten communities on the volcano’s southwestern side was in 1950. Since that eruption, several subdivisions have sprung up, including one of the state’s largest, Hawaiian Ocean View Estates, and the population has climbed from 8,000 to more than 18,000. “A lot of new people have come in not realizing they are settling on an active volcano,” says Jim Kauahikaua, head of HVO. According to a survey conducted in 2003, less than 25 percent of Big Island residents living on the west and southwest coasts knew that Mauna Loa had erupted in the previous 50 years.

The passage of time has also left a shortage of firsthand experience among those tasked with responding to the eruption. When asked how many geologists currently working at HVO were around for the previous eruption, Trusdell gives a sobering response: “one,” himself. The statistics are even bleaker at Hawaii’s state Civil Defense Agency, the group in charge of emergency management, where there is no overlap.

Meanwhile, the risk of a future catastrophic Mauna Loa eruption grows as more people and buildings pack into known hazardous areas like Hilo and Hawaiian Ocean View Estates. And that’s why, despite Mauna Loa’s current silence, HVO geologists are already taking steps — upgrading their monitoring tools and talking with the public — to prepare Hawaii for another eruption.

Erupting vents on Mauna Loa's northeast rift zone near Pu‘u‘ula‘ula on March 25, 1984, sent massive 'a'a lava flows down a rift toward Kūlani. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

Mauna Loa may share an island with four other volcanoes — and it even shares the same general magma source, a hot spot currently positioned below the island — but its potential scope of destruction is unmatched.

The massive shield volcano, with active zones that sprawl 60 kilometers from the summit to the southeast and about 20 kilometers to the northeast, sits in the middle of the island. The other big topographic bumps are all relegated to outer vantages — the dormant Kohala to the northwest and Mauna Kea to the northeast, the active Hualalai to the west, and the currently erupting Kilauea to the southeast. No other volcano poses a threat to both the eastern and western sides of the island.

Part of the difficulty planning for a future eruption is anticipating where it will occur. Even after an eruption has started, it might not be so obvious. The 1984 event is proof of that.

The eruption started early in the morning on Sunday, March 25, 1984, with lava flows in Moku΄āweoweo caldera, the summit crater. A few hours later, eruptive fissures migrated southwest about 5 kilometers, reaching down to an elevation of 3,886 meters before the lava retreated to the 4,170-meter summit.

By late morning, however, new fissures had formed along the volcano’s northeastern side. A 2-kilometer-long “curtain” of lava fountained from the cracks, reaching up to 50 meters in height and releasing between 1 million and 2 million cubic meters of lava per hour.

Over the 22-day eruption, new fissures propagated farther down the mountainside, prompting several families living in Hilo’s upper reaches to voluntarily evacuate. Along the steepest slopes, lava oozed at speeds up to 0.2 kilometers per hour. The eruption produced seven distinct flows, the longest of which traveled more than 20 kilometers.

Damage due to the eruption was limited to some roads and power lines that were overrun by lava. The flows stopped 7 kilometers short of Hilo, but still threatened the only cross-island highway, Saddle Road, as well as a prison. Civil Defense closed the highway for the duration of the eruption as a precaution.

A geologist monitors the 1984 Mauna Loa eruption. Credit: Christina A. Neal, U.S. Geological Survey.

When the lava began flowing, Frank Trusdell was on Oahu working on a graduate degree in plant pathology. Trusdell, who had spent many summers working at HVO during and after college, called up his former boss, Reginald Okamura, to check in and was given a curt order: “Get over here.” Trusdell was on Mauna Loa two days later.

Jack Lockwood, now a consulting geologist, was the Mauna Loa geologist at the time of the eruption. “For the first week, we were concerned about Hilo,” Lockwood says. That is when the flows were dynamic and fast-paced. Due to Mauna Loa’s varied topography, the downslope lava switched composition from speedy lava, called `a`a (pronounced ah-ah), on the upper, steeper slopes to a slower-moving ropy form, called pahoehoe (pronounced pa-hoy-hoy), on the lower, flatter regions.

“Seeing how quickly lava moves, whether it is `a`a or the pahoehoe, makes me a believer that if you are not paying attention, you could die working around [the lava] when you are out on the flow fields,” Trusdell says. “There’s no latitude for error.”

For safety reasons, and to keep pace with the flows, monitoring was mostly done by helicopter or plane. Trusdell mapped the flows from aloft by sketching their margins in pencil on a topographic map.

After the eruption ended, Trusdell returned to school, switched to volcanology and eventually joined HVO as a temporary hire before taking over for Lockwood as Mauna Loa geologist in 1996.

In the event of a future eruption, geologists and emergency managers will work together to assess and respond to the threat in much the same way they did back in 1984.

The region around the eruption will be closed off to the public and air space will be restricted to those involved with the response. Civil Defense will handle road closures and evacuations using information about lava flow intensity and di"ection provided by the HVO geologists.

Currently, Trusdell is the only full-time HVO staffer devoted to Mauna Loa. That will change as soon as the volcano starts to show signs of restlessness, he says. By the time an eruption actually starts, the observatory will be manned 24/7 “so that somebody’s looking at all the data, all the time,” Kauahikaua says, which will require bringing in staff from USGS sister volcano observatories in Alaska, California and Washington.

Unlike in 1984, when there was only one seismometer used to measure earthquakes near Mauna Loa’s summit — and it was turned off the night of the eruption — scientists today have more and better monitoring tools collecting data all day and night."

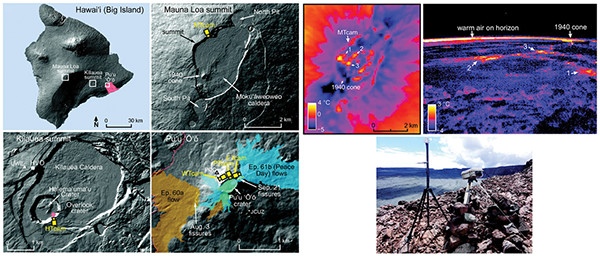

Trusdell and the other HVO geologists collect data from nearly 50 instruments speckled across Mauna Loa. Seismometers record earthquake activity at more than 15 different locations. Nearly a dozen tiltmeters measure how much the ground inflates, or “tilts,” due to the volcano’s internal accumulation of lava. Two shoebox-sized cameras are positioned along a section of the volcano’s most recent areas of activity, offering continuous real-time views of the summit crater and the upper northeast rift zone. And more than 20 GPS devices connect to satellite systems and provide geologists with precise indications of motion, accurate down to a few millimeters, which are used for map-making.

HVO geologists collect data from nearly 50 instruments — everything from seismometers to tiltmeters to thermal cameras — speckled across Mauna Loa. Credit: all: Patrick et al., Journal of Applied Volcanology (2014).

Then there are the alarms. For example, a Mauna Loa summit seismometer may trigger if more than four earthquakes occ"r in an hour, and then an alert is sent directly to the HVO geologists’ cellphones and email. Likewise, th"rmal cameras measure ground surface temperatures and send alerts if the temperature observed passes a certain level; tiltmeters also send alerts if the ground inflates rapidly within a short time.

The observatory’s alarm system is flexible, says HVO geophysicist Weston Thelen. “Thresholds now will likely be too sensitive once activity ramps up,” he says. As future activity unfol"s, “we may develop new alarms … we need to be ready to move quickly to address needs as they occur.”

“long with technological advances, scientists are now much better informed about Mauna Loa’s long eruptive history, courtesy of years of intensive fieldwork and mapping. The widespread and detailed mapping of Mauna Loa “is unprecedented for any other volcano in the world,” Trusdell says. That’s because of the volcano’s massive size: It is almost as big as the rest of the Hawaiian Islands put together. With clues from the giant volcano’s eruptive history, he has been working to simulate what future eruptions may look like.

“To evaluate risk, to evaluate the future, you have to know the past,” Lockwood says.

On June 1, 1950, at 9:04 p.m., Mauna Loa started quaking. Less than 30 minutes later, Mauna Loa's upper southwestern flank (higher than 2,400 meters elevation) glowed. Credit: Gordon A. Macdonald, U.S. Geological Survey.

In the past 200 years, just one eruption, in 1880, has sent lava into Hilo’s current city limits. Based on mapping of old flows, it appears that the lava stopped about 1.5 kilometers short of the old city limits. But because the city has grown since then, the old flows are now partially covered with houses, parks and roads.

Trusdell used a prehistoric flow similar to the 1880 eruption as the basis of his representative worst-case scenario for Hilo. To determine the impacts of such an eruption occurring today, he first accumulated infrastructure and tax data, including identifying the city’s critical infrastructure — airports, bridges, police stations, electrical power plants and nursing homes — and its monetary value. Trusdell only accounted for land improvements (anything built on top of the land), not the value of the land itself. He also calculated a cost per mile of road.

If we take the historical lava flow and apply these modern parameters, Trusdell says, then we can start to assess what could happen. The results are grim: The eruption could cause approximately $1.2 billion in damage. And “this estimate is conservative,” he adds.

For an eruption heading for Hilo, there is a silver lining, however: Lava flows would likely take weeks if not months to reach the city, giving residents ample time to pack up and leave.

But this is not true of all Mauna Loa eruptions. If an eruption in the summer of 1950 is any indication, people on the southwest side of the island would have far less time to respond — on the order of hours to days.

On June 1, 1950, at 9:04 p.m., the massive mountain started quaking. Less than 30 minutes later, Mauna Loa’s upper southwestern flank glowed fire-engine red. The brief time between the first tremor and the appearance of lava presaged the heart-racing pace of the eruption.

Several flows, or lava “fingers,” stretched down the mountainside that night, one a raging river of lava that crossed the region’s only exit route, Highway 11. The burning asphalt released clouds of noxious black smoke. The flow then consumed a post office, multiple houses and a gas station before emptying into the ocean. The flow took only 3.5 hours to reach the ocean, one of the fastest times ever recorded for flows traveling more than 30 kilometers. A combination of high lava output and, more importantly, steep slopes contributed to the speed of the lava flow, which reached about 10 kilometers per hour.

By the end of the eruption on June 23, 1950, Mauna Loa had produced eight discrete flows and enough lava to fill the Empire State Building more than 358 times. Disruptions to daily life continued well after the eruption’s end. Transportation to and from many homes and farms was cut off by flows, and it took weeks for the lava to cool enough for new roads to be paved. And they did get paved, and new roads, buildings and infrastructure were built.

Today, the southwestern stretch of Highway 11 is lined with real estate signs, from the western town of Kailua-Kona down to the Hawaiian Ocean View Estates subdivision, which is built atop fissures dating to an 1887 eruption. And the real estate market is growing, despite the risks. “ccording to Arnold Rabin, a Big Island real estate agent for 36 years, prospective buyers show a range of concern about the volcano; some care a lot and others not at all.

“I don’t think many people think of it in their day-to-day existence,” he says. Personally, he adds, “I choose to live here. The pros far outweigh the cons.”

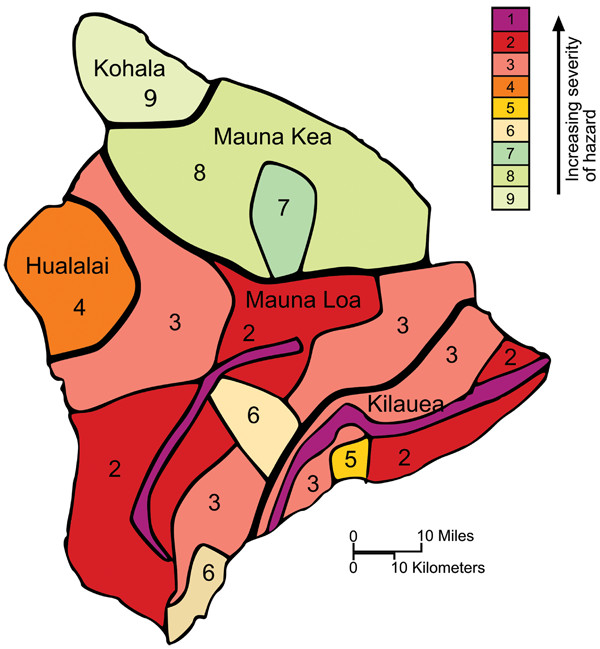

In general, realtors refer people to the HVO website, which displays a map of volcanic hazard zones (or lava zones) on the Big Island — ranked one through nine, with zone one the most dangerous — or to a 1997 USGS handbook titled “Volcanic and Seismic Hazards on the Island of Hawaii,” which covers volcano, earthquake and tsunami threats.

HVO researchers have created a map of volcanic hazard zones on the Big Island — ranked one through nine, with zone one being the most dangerous. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

Prospective buyers are made to sign the Hawaii Island Disclosure, a two-page document out"ining aspects of property ownership particular to the island, before a purchase goes through. But even in that, mention of volcanoes is buried in a paragraph sandwiched between property taxes and wastewater disposal. The disclosure notes that volcanoes “may affect the availability, limits and cost of property and/or liability insurance.” The translation, Rabin says, is that banks and insurance companies steer clear of the most hazardous zone one, and sometimes lava zone two, offering no loans, mortgages, or insurance coverage to people living there.

But where private companies don’t offer coverage, the state fills the gap. Starting in 1992, the government created the controversial Hawaii Property Insurance Association (HPIA), which offers insurance to residents in the riskiest parts of the island, including the southwest rift zone. In 2013, HPIA had more than 2,190 policyholders in the state of Hawaii, and 40 percent of them were in the Big Island’s lava zone two.

According to a 2008 article in the Honolulu Advertiser, “the state-created HPIA has made rapid development possible in precisely those areas of the Big Island most likely to be devastated by lava flows from the Kilauea volcano, or from future eruptions of Mauna Loa volcano.”

Remnants of Mauna Loa's eruptive history dot the landscape. Credit: ©Brocken Inaglory, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Volcanoes rarely blow without warning. Eruptions are preceded by many subtle signs in the form of cracks, bulges, quakes and steam. In the case of Mauna Loa, geologists say they will likely have several months to a couple of years to prepare. However, whether that’s enough time to prepare the general public is not a gamble that Trusdell says geologists are willing to make.

Every January for the past five years, HVO has hosted a public outreach event: Volcano Awareness Month. Geologists give talks about the island’s various volcanoes and their respective hazards, both within the national park and in towns across the island. Trusdell’s annual speech is titled, “Mauna Loa: How Well Do You Know the Volcano in Your Backyard?”

“People should be aware of where the hazards are,” Trusdell says. And if you’re in the hazard zone, “you can reduce your personal risk by being prepared.” Stock an emergency kit with food, medicine and clothes; keep copies of medical and financial papers; and devise plans to connect with family and/or friends during an emergency.

Conversations regarding Mauna Loa among scientists, officials and the public are focused on reacting — laying out plans for what the geologists, disaster managers or individuals will do when an eruption starts. For the Mauna Loa hazard to feel real, Trusdell says, Hawaii residents need a more frequent reminder of Mauna Loa’s hazard than his annual talk. That’s why HVO shares information about changes in the volcano’s physical condition whenever something is detected, no matter how small.

Recently, there has been a change — an uptick in earthquake swarms measured around the volcano. Although “this is definitely a change,” Kauahikaua says, it doesn’t necessarily mean that a new eruption is brewing. For an eruption, “we’d be looking for a lot more signs” and a lone earthquake swarm “is only one factor — and it’s a weak one at this point,” he says.

At the very least, however, the earthquake swarms are a reminder of Mauna Loa’s continued active status. “It’s not a dead volcano yet,” Trusdell says.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.