by Sara E. Pratt Thursday, September 11, 2014

On the evening of July 28, 1996, archaeologist James Chatters received an unexpected call at his home in Richland, Wash., from the local coroner. Two spectators at the local hydroplane races had found a skull in Columbia Park on the banks of the Columbia River near Kennewick, Wash. The coroner wanted Chatters, a paleontologist and forensic anthropologist affiliated with Central Washington University who often consulted for Benton County, to look at the skull and determine if it belonged to a recent murder victim. When the coroner arrived with the skull in a 5-gallon bucket, Chatters had scant notion that the discovery would end up challenging the reigning theory of the origins of the first Americans and would embroil scientists in a protracted, precedent-setting legal battle against the federal government.

Chatters’ first impression of the skull was that it had belonged not to a modern murder victim, but a 19th-century European settler. The skull, darkened with age, had a long, narrow braincase and a narrow face with little protrusion and a prominent nose. Chatters identified it as a Caucasoid skull type, having features similar to the skulls of those with ancestors in western Asia, Europe and northern Africa. The skull lacked the distinctive features of Native American skulls, which exhibit a broad face with wide flat cheekbones and more facial protrusion, similar to the people of northeastern Asia, from areas such as Mongolia and Siberia.

Although the skeleton was not identified as Native American, because the discovery was made on federal land administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Corps immediately informed the local Native American tribes. Under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), human remains discovered on federal lands or being held in museums must be repatriated to the closest living indigenous tribe to whom a cultural affiliation or genetic link can be established. Following Native American religious customs, the bones are then usually reburied immediately, often in a secret location, with no further scientific study, which many tribes believe to be desecration.

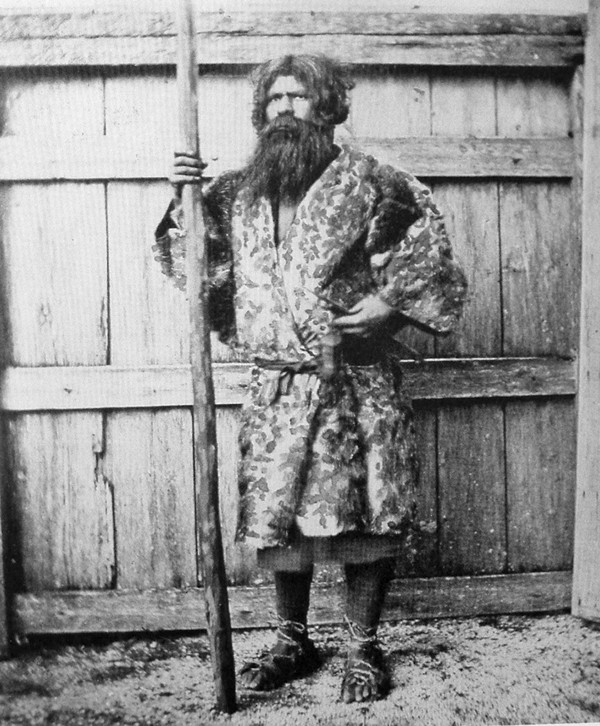

Kennewick Man's closest modern relative is thought to be the seafaring Ainu people of Japan. The Ainu were once widespread in coastal Asia, but today, only a small population remains on the island of Hokkaido. This Ainu man was photographed in 1880. Credit: Public Domain.

To further identify the skeleton, Chatters needed to see the rest of it. With a permit issued by the Corps, Chatters returned to the site of the skull’s discovery, where debris and artifacts from a pioneer homestead had also been washed out of the muddy riverbank. He found more than 300 pieces of bone, including the arm and leg bones and the jaw, which is especially helpful in identification.

Back in his lab, Chatters reassembled the nearly complete skeleton, which belonged to a 45- to 55-year-old male who had survived several injuries, including one that left an object embedded in his hip. To Chatters’ surprise, an X-ray and CT scan at the local hospital revealed the object was a Cascade point, a leaf-shaped blade with serrated edges made by prehistoric people living in the Northwest between roughly 9,000 and 5,000 years ago.

How did a Caucasoid-looking skeleton come to have a stone-age spear point in his hip? With permission from the Corps, Chatters sent a tiny piece of bone to the accelerator mass spectrometry lab at the University of California at Riverside for radiocarbon dating.

The results provided another surprise. The bones had a radiocarbon age of 8,400 years, which translates to roughly 9,300 calendar years, making Kennewick Man, as Chatters’ wife had begun to call the skeleton, one of the oldest and most complete skeletons found in the Americas.

Chatters recognized the value of such a rare find to scientists studying the earliest humans to arrive in America, called Paleo-Indians or Paleo-Americans. At the time, the reigning “Clovis First” theory held that a single wave of hunters from Eastern Siberia — dubbed the Clovis people and known for the characteristic spear points they crafted — had migrated across the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last ice age, roughly 13,500 years ago, through an ice-free corridor and rapidly migrated south.

Thus, it stood to reason that anyone inhabiting America at the time of Kennewick Man must have been a direct ancestor of modern Native Americans.

Five different tribes claimed Kennewick Man as their ancestor: the Umatilla, Colville, Wanapum, Nez Perce and Yakama, some of which had only occupied the area since the 1800s.

The case had similarities to the mummified remains of a 40-year-old man dressed in rabbit skin robes and wearing fur moccasins who had been found in Spirit Cave in Nevada in 1940. The mummy, with preserved hair, skin and large intestine still containing a last meal of fish, had been resting in the Nevada State Museum since its discovery. In 1994, as part of an effort to reanalyze old discoveries with new scientific techniques, a radiocarbon analysis was conducted on Spirit Cave Man, revealing that he was also more than 9,000 years old.

Further analysis of the Spirit Cave skull showed it bore a resemblance to the indigenous Ainu people of Japan, whose features early anthropologists described as Asiatic-Caucasoid. The Ainu once occupied a large part of coastal Asia and are thought to be a remnant of the earliest population of modern humans to arrive in Asia. The mummy also had features matching those of the Moriori of Polynesia, the Zulu of Africa, and the Norse, a medieval Norwegian culture.

Physical anthropologists, including Doug Owsley, the curator of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., determined that Spirit Cave Man bore little resemblance to the Native American Plains Indians. Nevertheless, the Paiute-Shoshone Tribe attempted to claim ownership of the remains under NAGPRA and halt the scientific study.

In Washington, the discovery of another unusual ancient skeleton again raised the question: Who were the first Americans and where did they come from?

Well-preserved skeletons from between 9,000 and 13,000 years ago are rare archaeological finds. Some of the more complete specimens include Spirit Cave Man in Nevada, Buhl Woman in Idaho, and the Horn Shelter man and child in Texas. Several finds have been repatriated to Native American tribes and reburied without further study. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

By the mid-1990s, evidence was mounting that the first Americans had arrived thousands of years earlier than previously thought. In South America, the discovery of the Monte Verde sites in southern Chile had been dated to roughly 15,000 years ago. In North America, the Meadowcroft Rockshelter, a campsite beneath a limestone overhang in southwestern Pennsylvania, revealed signs of human habitation as far back as 20,000 years ago. At Meadowcroft, archaeologists also discovered stone spear points that differed from Clovis technology but closely resembled stone points in use in Japan about 24,000 years ago.

It was beginning to appear that the first Americans arrived during or before the last ice age, in multiple waves, taking various routes from different regions, possibly even traveling to the Pacific coast in boats.

Few human remains from this time have been found, making each discovery valuable to archaeologists who are trying to answer questions about early human populations. Only about a dozen semi-complete skeletons between 9,000 and 13,000 years old have been found in North America.

Several of those, however, have been repatriated to Native American tribes and reburied without any further scientific study. Burial in a different soil environment than that in which they were preserved can cause rapid deterioration, leaving archaeologists to lament that these skeletons are now likely forever lost to science — along with any knowledge that might have been gleaned in the future using scientific techniques that had yet to be developed at the time of discovery, such as DNA analysis.

In early September 1996, Chatters was scheduled to take Kennewick Man to Owsley at the Smithsonian, but before he could, the Corps seized the skeleton from the Benton County Coroner. Despite a concerted effort by many scientists to make the case for study, the Corps announced that it had summarily determined the skeleton to be Native American and that the bones would be immediately repatriated to the Umatilla tribe for reburial.

In October 1996, eight anthropologists, including Owsley, sued the Corps, in an attempt to gain the right to study the remains. The scientists argued that because the remains could not be established as Native American, or tied to any indigenous tribe, then NAGPRA did not apply. The case came before Magistrate John Jelderks of the U.S. District Court in Portland, Ore., who prevented the immediate repatriation of the bones, but put the court case on hold after the Corps promised to investigate further.

In 2000, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt announced that because the remains were in the United States prior to 1492, they were necessarily Native American and would be repatriated to all five tribes.

The court blocked the action and reopened the case. The scientists’ attorneys argued that ancient remains are the common legacy of all Americans and that basing a repatriation decision on the year 1492, which is not specified in NAGPRA, would set a bad precedent. For example, Viking remains could be repatriated to an unaffiliated group.

Two years later, after months of hearings and deliberation, the judge ruled in favor of the scientists in a 73-page decision that criticized how the Corps and Department of the Interior handled the case. Given the prehistoric age of the remains, and the inability of scientists to establish a cultural affiliation to a living tribe, the judge determined that NAGPRA did not apply to Kennewick Man. The remains instead fell under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA), a 1979 law enacted to protect and conserve archaeological discoveries made on federal lands, specifically for the purposes of scientific study. The tribes appealed and, in 2004, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the ruling, agreeing that the remains could not be linked to any living tribe.

Today, the bones of Kennewick Man are held at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington in Seattle, and, by court order, have been made available for limited scientific study. In 2005 and 2006, a group of scientists convened at the museum to conduct a thorough study of the bones; however, no results have been published yet.

Although the bones can be studied, the site on the Columbia River where Kennewick Man was discovered, which geologists and paleontologists wanted to further study, has been forever lost to science.

In 1998, while the court case continued, the Corps ordered the site buried, despite an act passed by Congress expressly forbidding it, which was awaiting presidential signature. The Corps dumped 1,800 metric tons of rock and soil onto the site, encasing the bank from which the bones had eroded. The construction crew then planted Russian olive trees with fast-growing roots that would further desecrate any remaining archaeological evidence.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.