by Timothy Oleson Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Glass replicas of the nine main gems cut from the original rough Cullinan. At top left is the 530.2-carat pearshaped Cullinan I, dubbed the

Each day, thousands of visitors to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History view the rare and spectacular Hope Diamond, a 45-carat blue diamond. And dozens of diamonds bigger than the Hope — with names like Excelsior, Incomparable and Jubilee — have also been retrieved, cut and polished to perfection.

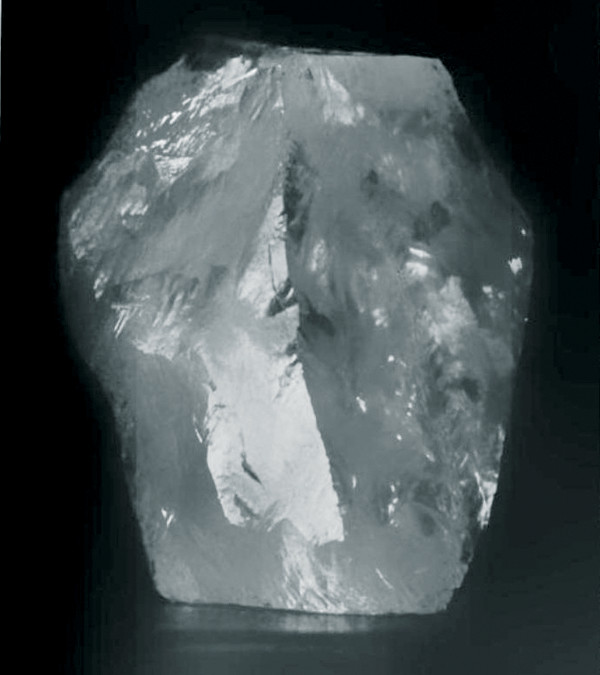

There is more to diamonds than their mass to be sure, but for sheer size, one find stands far above the rest. Named for the owner of the South African mine where it was unearthed in January 1905, the Cullinan Diamond weighed in at an astounding 3,106.75 carats (621 grams). It easily bested the 972-carat Excelsior diamond, found 12 years earlier, to become the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found. And 109 years later, the Cullinan still holds the record. Not surprisingly, the diamond — split into more than 100 separate gems soon after its discovery — has had an illustrious history.

In the rough, the nearly colorless Cullinan Diamond measured about 10-by- 6-by-6.5 centimeters. Credit: Wodiska, Julius,

The vast diamond wealth of South Africa was first realized in the late 1860s, and with the founding of the famous Kimberley mines in 1871, the country’s diamond rush began. The land on which these mines were located (owned at the time by the de Beer brothers, whose surname would become synonymous with the world’s diamond trade, though they themselves were never involved with the company that bears it) hosted a large vertical “pipe” of peculiar volcanic rock emplaced in the surrounding strata and emerging at the surface. Termed “kimberlites” because of the proximity of this find to the town of Kimberley, such pipes are thought to have erupted from depths of 150 kilometers or more beneath Earth’s surface, based on the exotic porphyries of mantle materials they contain. Typically, they are found bearing olivine, ilmenite, phlogopite, diopside, garnet and occasionally, among other minerals, diamond.

The Kimberley pipe was the first of many diamond-bearing kimberlites found in the region. Mining began in 1888 at a pipe near Jagersfontein, which five years later produced the Excelsior diamond. And in late 1902, following the Second Boer War — which left the former Dutch-speaking Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic as British colonies — a builder-turned-prospector named Thomas Cullinan purchased land he suspected might harbor magnificent gems of its own.

Located east of Pretoria and more than 500 kilometers northeast of the Kimberley and Jagersfontein mines, Cullinan’s Premier Mine quickly proved successful. In its first year of operation, it produced 750,000 carats of diamonds. And there was much more to come.

On Jan. 26, 1905, just over two years after Cullinan purchased the land, he was treated to a welcome surprise: a stunning behemoth pried from the mine’s wall. Different accounts of its sighting vary in the details — including the exact day on which it occurred — but, in general, the story goes that the mine manager, Frederick Wells, spied (or was alerted by a mine worker to) a prominent stone glittering in the afternoon sun in the wall of the open-air pit while on a routine inspection. Uncertain whether it was real or merely a piece of glass, Wells scurried down the steep wall for a closer look. After dislodging and dusting off the object, he held in his hand a clear, unpolished stone about the size of a fist.

Some at the mine, including Cullinan himself at first, doubted it was an actual diamond given its immense size. One worker purportedly went so far as to pluck it from Wells’ hand and toss it out the window of the mine office in disbelief. But petrographic analysis confirmed its identity as the real thing. And there was even speculation, given that several smooth cleavage faces were exposed on the rough diamond, that it had broken off from what was once an even larger stone at some point in its geologic history, though this was never confirmed. Regardless, the Cullinan Diamond, as it was officially named, quickly gained worldwide fame.

In February 1905, after a brief stint on public display in Johannesburg, the diamond was sent to England both for inspection by King Edward VII and for it to go on display for potential buyers. Its notoriety meant that security of the diamond during shipment was a risky endeavor. As a diversion for would-be thieves on its seaward trip to England, a steamship carrying a replica of the stone, under guard and stowed in the ship’s safe, was dispatched with fanfare as if its cargo was genuine. Meanwhile, disguised as an ordinary package, the true Cullinan was shipped off via parcel post to London. Both, it turned out, arrived safely.

Selling the stone proved difficult, both because of the high asking price and the perceived difficulty in cutting such a massive gem. It’s unclear if there was a set asking price, although in “Famous Diamonds,” Ian Balfour notes that each time the Cullinan “was removed from the bank it was insured by a ‘floater’ policy of £500,000 even though it was, at all times, guarded by a squad of detectives.” (Half a million pounds in 1905 is equivalent to about £51.5 million, or $83 million, today.) Finally, in 1907, the government of the Transvaal Republic purchased the Cullinan from the Premier Company and presented it in November — in a show of loyalty to the British Crown, which had recently granted self-rule to the Transvaal — to Edward VII for his 66th birthday. The king then entrusted the rough stone to the celebrated diamond handlers of the I.J. Asscher company in Amsterdam to be cut. The cutting would become “the major event of gem history in the year 1908,” Julius Wodiska wrote in his 1909 volume, “A Book of Precious Stones.”

The Cullinan arrived in Amsterdam in January 1908. In anticipation of receiving the diamond, the Asscher brothers had been studying how best to handle it. Noting a visible imperfection in its center, they decided it could not be cut and polished as a whole diamond, but that it had to be split into separate pieces. In early February, Joseph Asscher began work on it.

After incising a 6.5-millimeter-deep groove with a diamond saw, a comb-shaped steel blade was placed into the groove. With a crowd of onlookers and tension in the air, Asscher rapped the back side of the blade with a steel rod. The knife broke, leaving the diamond unscathed. Asscher regrouped, fitted a second, larger blade into the incision, and “with beads of sweat on his face, in tense silence … [he] tapped it sharply,” Balfour recounts. This time, the diamond split in two, right through the impurity in the center and according to plan. Whether Joseph Asscher fainted upon seeing the stone split — a popular but contested tale — is unclear.

The process of further splitting the two pieces, along with grinding and polishing the final gemstones, lasted into September 1908. It was difficult and anxious work, requiring tools and techniques never before used to prepare diamonds. In the end, nine major gems — weighing between 530 and 4.4 carats and simply named Cullinan I through IX according to their size — were crafted, along with 96 smaller stones. Balfour notes that, in total, the polished gems amounted to 1,055.9 carats, meaning nearly two-thirds of the original diamond was trimmed away during processing.

The two largest gems, the 530.2-carat pear-shaped Cullinan I, dubbed the “Great Star of Africa,” and the 317.4-carat cushion-cut Cullinan II, were presented to the British king and queen in November 1908. They were subsequently fitted into the crown jewels — the British Royal Scepter and the Imperial State Crown, respectively — where they remain today on display in the Tower of London.

Although initially held by the Asscher company as payment, which also retained all of the smaller stones, the remaining named Cullinans were soon purchased and gifted to the British royal family. Over the last century, these seven stones have been set into various brooches, necklaces and other royal adornments housed at Buckingham Palace.

The open pit of the Premier Mine, where the Cullinan Diamond was unearthed, about 40 kilometers east of Pretoria, South Africa. Credit: ©Paul Parsons, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

Diamond mining continues to be a major industry in South Africa, with production varying between about 6 million and 16 million carats in the last decade, according to data from the South African Chamber of Mines. In 2011 (the last year with available data), South Africa ranked fourth internationally, behind Botswana, Russia and Canada, in terms of the value of diamonds produced.

Although many of the country’s historic mines have closed, the Premier Mine — renamed the Cullinan Diamond Mine for its centenary anniversary in 2003 — is still active today. Many large diamonds have been unearthed since that first big find, including a 755.5-carat rough yellow-brown diamond found in 1986. Once cut, this stone, which would come to be named the Golden Jubilee, surpassed the Great Star of Africa as the largest cut diamond in the world at 545.7 carats. Nonetheless, the original Cullinan is still regarded by most as the greatest diamond ever found.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.