by Timothy Oleson Thursday, January 7, 2016

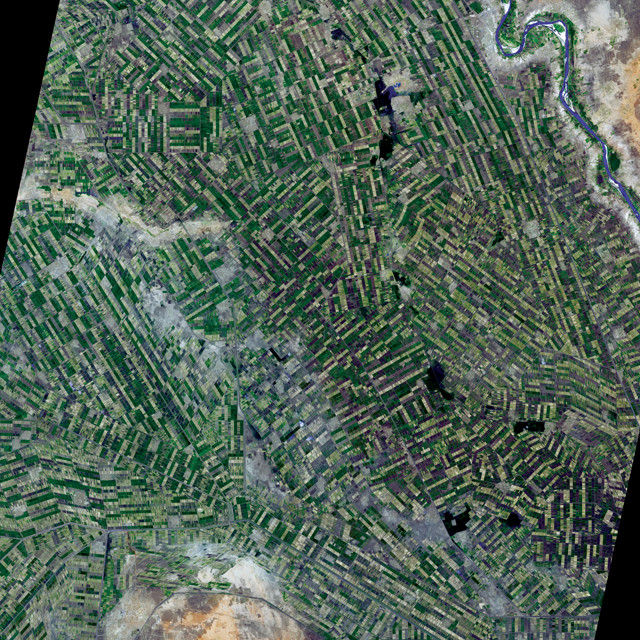

Croplands in the Gezira Scheme in Sudan, near the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile, are watered by a vast network of irrigation canals. Credit: NASA.

Researchers have found that large-scale agricultural irrigation, intended to supplement precipitation, may actually drive rainfall away, potentially exacerbating conditions in some areas while improving them in nonirrigated lands.

In addition to adding moisture to the ground, irrigation affects local air temperature, humidity and winds, all factors that contribute to weather patterns. Previous modeling has suggested that large-scale irrigation can shift where rain falls, particularly in arid regions like the African Sahel — the transitional zone between the Sahara Desert and wooded savanna farther south — where small changes in moisture levels may have outsized effects on weather. But little has been done to verify model results for Africa with observations of actual conditions.

Ross Alter of MIT and colleagues used a regional climate model to investigate part of the East African Sahel surrounding what’s known as the Gezira Scheme, a nearly 9,000-square-kilometer area of irrigated land in central Sudan, between 1979 and 2008. The model suggested that during the summer months when the Sahel receives most of its annual precipitation from the African monsoon, precipitation levels fell by as much as 2 millimeters per day over the irrigated area while they increased over nonirrigated areas farther east. The researchers then looked at trends in a historical precipitation dataset covering the region, as well as in separate observations from six weather stations in and around Gezira. They found that the relative patterns were consistent with their model results. Shifts in surface air temperatures and streamflow over the same time period were also consistent, they noted.

A “causative link between irrigation development and rainfall modification may have numerous implications for agricultural, hydrologic, economic and political interests both inside and outside these irrigated areas,” the researchers wrote in Nature Geoscience.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.