by Mary Caperton Morton Friday, October 31, 2014

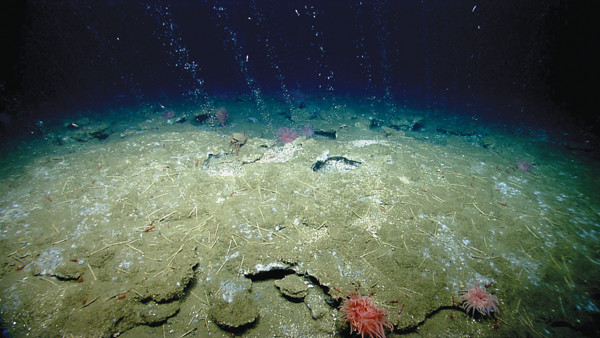

Methane bubbles stream from seafloor sediments off the coast of Virginia north of an area called Washington Canyon. Credit: NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, 2013 ROV Shakedown and Field Trials in the U.S. Atlantic Canyons.

The release of methane from seafloor sediments may have a significant influence on global climate, but the ubiquity and stability of such pockets is not well understood. Now the discovery of hundreds of methane seeps on the seafloor along the U.S. East Coast suggests that such reservoirs may be more common along passive margins than previously thought. The easily accessible region may prove to be an ideal natural laboratory for studying how such seafloor methane may influence water temperatures and ultimately climate.

Methane is often found naturally leaking from the seafloor, particularly in petroleum basins like the Gulf of Mexico or along tectonically active continental margins like the U.S. West Coast, but such plumes were not expected along passive margins, like the east coast of North America, says Adam Skarke, a marine geologist at Mississippi State University and lead author of the new study in Nature Geoscience.

Using multibeam sonar originally designed to create 3-D maps of the seafloor, Skarke and colleagues located 570 seeps at water depths between 50 and 1,700 meters between Cape Hatteras, N.C., and Georges Bank off the coast of Cape Cod. “We didn’t expect to see so many plumes, as many of the geologic features associated with natural gas seepages are not present along the East Coast,” he says.

The study is the first to map seepages in this region at any level of detail, says John Kessler, a geochemist at the University of Rochester in New York who was not involved in the new study. Finding these seeps, he says, is “not an easy task: We’re trying to find bubbles of gas coming out of the seafloor with a mile of water under the boat.” But, he adds, it does seem like “the more people who go looking with the right equipment, the more of these seeps we find.”

The key breakthrough was technological, Skarke notes. “This is the first time that we have had the appropriate sonar technology to be able to survey a large region with the kind of resolution needed to detect gas bubbles on the seafloor.”

Although the number of active seeps was surprising, the amount of methane being produced — a conservative estimate made based on video observations of bubble size and rate — “is likely a small drop in the global carbon budget bucket,” Skarke says. “But it does suggest that there might be more widespread global seepage along passive margins and all of those [together] may be playing an underestimated role in warming ocean temperatures and climate change.”

The fate of the released methane is still unknown. “At this point, we don’t have any evidence that the carbon being produced in the methane seeps is leaking into the atmosphere,” he says. “We’re pretty sure it’s dissolving into the water and being microbially oxidized so it likely doesn’t have a direct link to the atmosphere.”

Now that the region has been identified, it may prove to be an ideal natural laboratory for studying the relationships between methane, water temperature and climate, says Kessler, who wrote an accompanying commentary in the same issue of Nature Geoscience.

“Many variables can influence the release of methane from the seafloor. The nice thing about this region is that it’s a relatively simplified environment,” Kessler says. Methane seeps in petroleum basins, for example, can be influenced by deeper geologic reservoirs of oil and gas, and those in the Arctic are often complicated by permafrost and phytoplankton blooms, which can produce fluxes of methane under different conditions.

“Here we should be able to do direct comparisons between the stability of methane and bottom water temperatures, which is one of the more critical relationships we need to understand to define the link between methane and climate,” Kessler says.

“This is an area of the ocean that’s relatively accessible, near a populated coastline with a lot of resources and powerful oceanographic research partners,” Skarke says. “This study really highlights the need for more surveys along this margin and others around the world.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.