by John-Manuel Andriote Tuesday, May 13, 2014

In 2007, I returned to eastern Connecticut, where I grew up. Driving north on Interstate 395 past towns like Norwich and Griswold, I was struck by the many old gray stone walls tumbling off into the forests along the highway. Realizing that the trees in those forests weren’t particularly old, I surmised that those forests had once been cleared farm lands.

Casually wondering what had happened to the farms led to a journey of discovery through the forests and fields of New England.

My journey started with the book “Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History of New England’s Stone Walls” by University of Connecticut geology professor Robert M. Thorson. Thorson — known to colleagues and friends as “Thor” — says he was “smitten” by the stone walls after moving his family from Alaska to Connecticut in 1984. At first, studying them was just a hobby for Thorson. “It wasn’t my job,” he says. “I had been teaching and researching. I ran a lab with graduate students and had funded projects … But I got interested in these stone walls as landforms, so I kept working on it.”

Laid stone walls along Route 169 in Canterbury, Conn. Credit: John-Manuel Andriote.

In 2002, Thorson published “Stone by Stone,” his first book on the topic, and he and his wife Kristine founded the Stone Wall Initiative in conjunction with the publication, which Thorson describes as the first geoarchaeological study of New England’s stone walls.

Like the book, the Initiative aims to promote scientific understanding of the walls and advocate for their protection as cultural and ecological resources. Since the book’s launch, Thorson has spoken to thousands of stone wall enthusiasts, authored numerous articles on the subject, and seen his book become the basis of a documentary called “Passages of Time.”

On a brilliant afternoon in January 2014, I joined Thorson for a guided tour of the stone walls in Brooklyn, Conn. The area features many notable stone walls in large part because of its proximity to what Thorson calls “the geological and agricultural center of interior New England,” which provided abundant stones of the perfect size and shape to make them. Thorson notes in “Exploring Stone Walls,” his 2005 field guide, that January is one of the best times in southern New England for stone wall viewing. “Like a negative to a photograph,” he writes, “walls are most visible when life is most invisible. Typically this occurs in January when snow frames the wall from bottom to top and when the strengthening, crystal-clear sun casts strong shadows.”

As we toured the walls, I learned their story: It begins with glaciers during the last ice age, meanders through the Colonial and early New England farming eras, ebbs during industrialization in America as the walls were abandoned and fell into disrepair, and continues today with their memorialization in poetry and refurbishment.

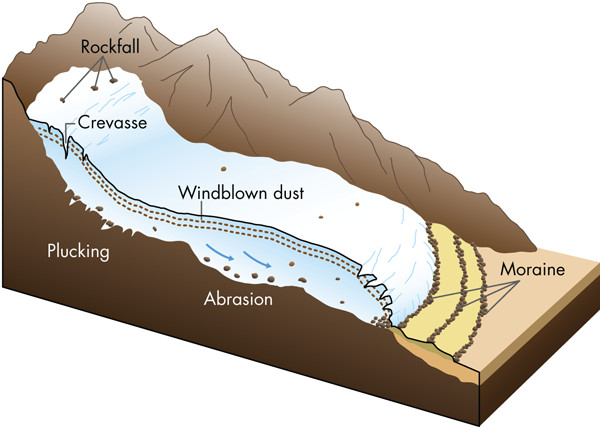

The stones in New England's stone walls were plucked from bedrock by the Laurentide ice sheet between about 30,000 and 15,000 years ago. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

The origins of New England’s wall stones date back to between about 30,000 and 15,000 years ago, when the Laurentide ice sheet — a remnant of which still exists in the Barnes Ice Cap on central Baffin Island — made its way southward from central Canada and then began retreating. “It stripped away the last of the ancient soils,” writes Thorson in “Stone by Stone,” “scouring the land down to its bedrock, lifting up billions of stone slabs and scattering them across the region.”

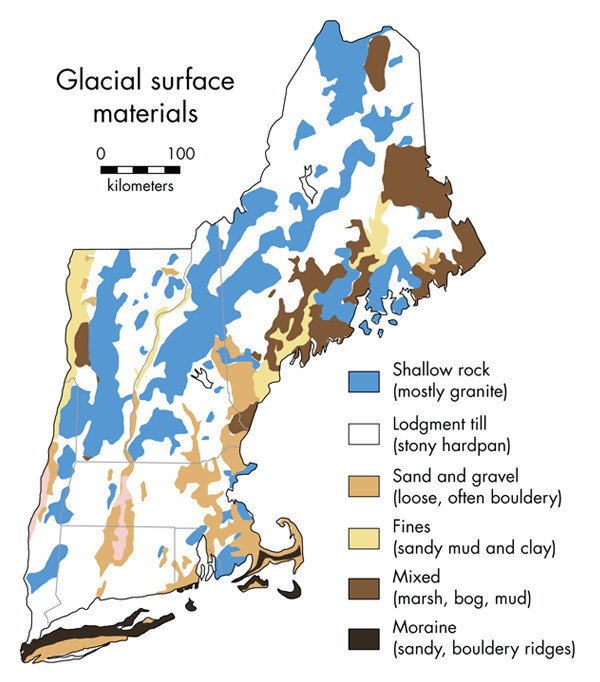

As the ice sheet melted and receded, it left behind deposits of unsorted material ranging in size from clay to massive boulders chiseled from the slate, schist, granite and gneiss bedrock of northern New England and Canada. The bucolic rolling hills and meadows of New England are formed of rich glacial soil called lodgment till — up to 60 meters thick — that was “almost single-handedly responsible for the success of the agricultural economy in New England,” Thorson says. A thinner, looser layer of rocks and sand called ablation, or “melt out,” till was left above the lodgment till. Most stone walls are composed of stones from melt-out till, which were “abundant, large, angular and easy to carry,” Thorson says, compared to the smaller, more rounded stones from the deeper lodgment till.

Although New England’s stone walls are popularly associated with the Colonial era, there weren’t actually many rocks lying around in the soil at that time. As evidence, Thorson cites Swedish botanist Peter Kalm, who toured New England in the mid-1700s. In his “Travels in North America,” Kalm observed of its forest soils, “[T]he Europeans coming to America found a rich, fine soil before them, lying loose between the trees as the best in a garden. They had nothing to do but to cut down the wood, put it up in heaps, and to clear the dead leaves away.”

Likewise, Colonial-era books on farming, encyclopedias and recorded observations do not mention stone walls, Thorson notes. Instead of stone walls, Colonial farmers used rail and zig-zag fences made of wood — far more abundant at the time than stone — to pen animals. It wasn’t until the latter half of the 18th century that early stone walls were first widely constructed in New England. Even then, other than in long-farmed interior areas such as Concord, Mass., the stone was typically quarried or taken from slopes rather than from fields.

The region’s stones lay deep in the ground, buried under thousands of years’ worth of rich composted soil and old-growth forests, just waiting to be freed by pioneers clear-cutting New England’s forests — a process that reached its peak across most of New England between 1830 and 1880.

Glacial action produced the raw materials for stone wall building. Granite, the most common rock in New England, also predominates in stone walls. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI, after Thorson, 2005.

Heating an average-sized New England farmhouse during the late 18th and early 19th centuries — which coincided with the waning years of the “Little Ice Age,” the unusually cool climatic period that lasted from the mid-1300s to the mid-1800s — required burning up to 35 cords of cut wood a year. Considering that one cord is 3.6 cubic meters of wood, it is easy to understand why New England’s cold winters, along with the construction of all those farm buildings, meant the demise of vast swaths of forest.

Widespread deforestation exposed New England’s soils to winter cold — scientists estimate winter was 1 to 1.5 degrees Celsius colder on average during the Little Ice Age than it is today — causing them to freeze deeper than they had before. This accelerated frost"heaving, and gradually lifted billions of stones up through the layers of soil toward the surface.

These stones weren’t conducive to farming, so, aided by their oxen, farmers hauled the stones to the outer edges of pastures and tillage lands, typically unceremoniously dumping them in piles that delineated their fields from the forest. (Some of these so-called “dumped walls” would later be relaid more intentionally when improved tools and equipment made rebuilding easier.) In the early days, artistry in stone wall building had to wait. The first priority was survival, which meant clearing land to grow crops and raise livestock.

At Harvard Forest — a 1,500-hectare forest laboratory and classroom established by Harvard University in 1907 in Petersham, Mass. — a series of dioramas in the Fisher Museum chronicles the landscape history of New England by depicting the changes on a single plot of land since the Colonial era. European settlement, and the beginning of deforestation, largely occurred in the 18th century. By the mid-19th century, 60 to 80 percent of the land had been cleared. After farming began to decline, abandoned pastures and fields rapidly developed into white pine forests, which obscured the stone walls. The pines were logged and succeeded by the mixed hardwoods seen today. Credit: photos by John Green, courtesy of Harvard Forest, Harvard University.

The types of stones and their abundance may have been familiar to those early farmers, who were mainly from the British Isles, Thorson says, because rock in New England is similar to rock in England and Scotland. England and New England have similar natural landscapes because both lands have a similar geologic history. Millions of years ago, England and New England were formed within the same mountain range near the center of Pangaea. So, he says, “the similar fieldstones on opposite sides of the Atlantic were created practically within the same foundry.”

But there was one important difference between these New World and Old World stones: Britain had long been deforested, with its subterranean stones brought to the surface, so its stone walls had been constructed hundreds, if not thousands, of years earlier.

Although the oldest documented stone wall in New England dates to 1607 — made by English settlers of the Virginia Company along the estuary of the Kennebec River north of Portland, Maine — most of the region’s stone walls were built in the Revolutionary period between 1775 and 1825, a period that Thorson calls “the golden age of stone wall building.” By then, the effects of deforestation on the soil were being fully felt; established farms were churning up tons of stones that had to be removed. Simultaneously, a post-Revolutionary War baby boom provided an abundance of young hands to help move them.

During this period, thousands of stone walls were built and thousands more were improved. Thorson writes in “Stone by Stone” that “farmers throughout the region began to look inward at their farms, not as safe havens from war, but out of pride in being American.” Their pride was reflected in the way they painstakingly refashioned the piles of stone and primitive dumped walls along their property lines into the now classical “double walls,” parallel rows of stone filled in with small stones (see sidebar, page 34).

Constructing the walls was labor intensive. For comparison, modern masons typically lay about 6 meters of stone wall per day, Thorson says. He estimates that 40 million “man days” of labor would have been required to build the more than 380,000 kilometers of stone walls in New England — enough to build a wall from Earth to the moon — reported by an 1871 fencing census. “This is an awesome amount of manual labor,” he says, “but it is trivial when compared to the much larger effort of getting stones to the edges of the fields in the first place. That job usually had been done stone by stone, and load by load, by the previous generation.”

Over a couple of generations, New England’s vast stone wall network was erected, and by the 1830s to 1840s, farms were also well established and farmers were no longer clearing as much land, said Christie Higginbottom, a research historian at Old Sturbridge Village, in the documentary “Passages of Time.” Old Sturbridge Village is a living museum of 1830s rural New England life located in Sturbridge, Mass.

As the 19th century progressed, changes in farming, in the nature of work, and in the political climate in the country all profoundly affected New England’s stone walls.

Farming was ubiquitous in Colonial America. Generations of subsistence farmers cleared and wrung their families’ nourishment from the land. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, however, that began to change. The establishment in 1787 of America’s first cotton mill — the Beverly Cotton Manufactory in Beverly, Mass. — launched one of the greatest transformations and population shifts in the young nation’s history. The American Industrial Revolution brought to New England’s cities thousands of young women and girls, in particular, who left behind their cooking, spinning, weaving and various other farm chores to earn money for their families as hired laborers in the region’s proliferating textile mills.

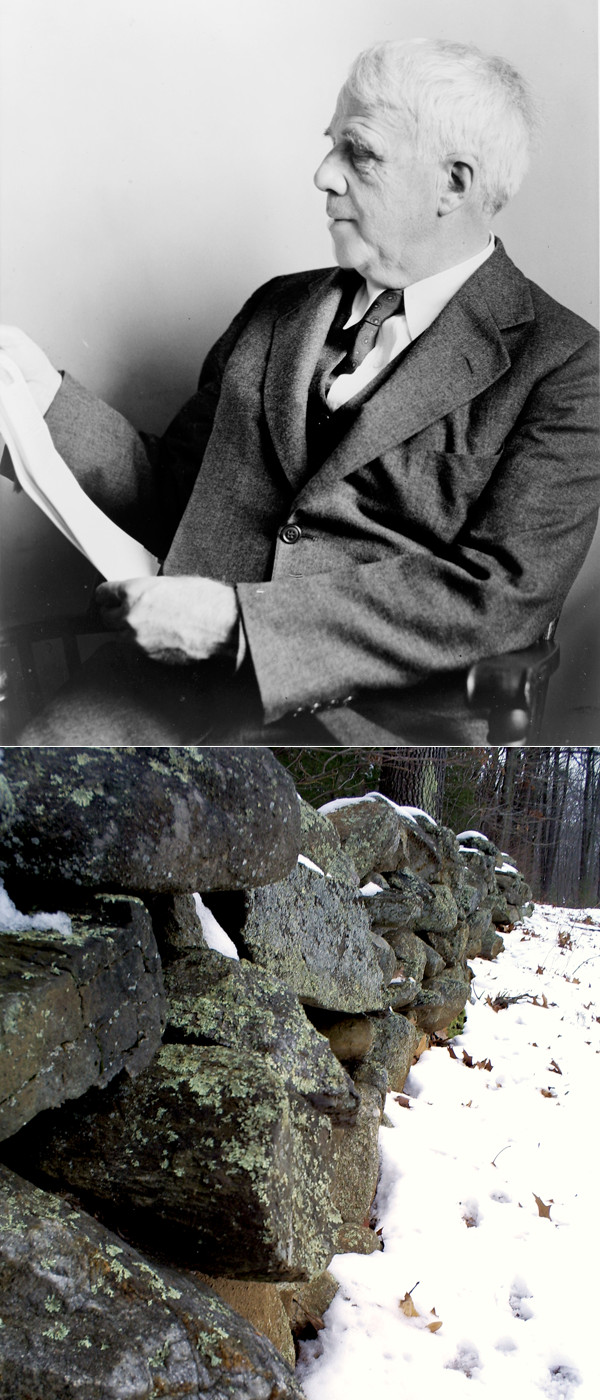

Robert Frost's poetry imbued New England's stone walls with mythological significance. He wrote about this stone wall, on his farm in Derry, N.H., in his poem "Mending Wall." Credit: top: Library of Congress/New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection; right: CCA 3.0

Farming itself was also changing dramatically with the invention of new tools, such as the cast-iron plow, and a more scientific approach to farming that maintained the soil’s fertility. Even these tools couldn’t help farmers recover from the so-called “Year Without a Summer” in 1816, when the massive eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 ejected ash and particulates into the global atmosphere, causing a “volcanic winter” that devastated crops. Between the loss of a year’s harvest and the start of an industrial depression in 1819, many more New Englanders abandoned their farms — and with them, the stone walls — to push westward into New York, Ohio and beyond

By mid-century, the exodus from the farms caused what Thorson calls a “psychological curtain” to descend upon the land and a “biological curtain” to arise, as vegetation overgrew many n"glected old walls. “If you walk away from walls in an open landscape,” if there are no cows to keep field" mowed, he says, “the walls are going to get covered with brush very quickly and they’re going to disappear. The white pines are going to shoot up. Within a decade of walking away from them, you’re going to have trouble seeing them.”

As early as 1850, naturalist Henry David Thoreau revealed in his journal how the rural stone walls had already come to represent something important about the character of New England. “We are never prepared to believe that our ancestors lifted large stones or built thick walls,” he wrote. “How can their work be so visible and permanent and themselves so transient? When I see a stone which it must have taken many yoke of oxen to move, lying in a bank wall … I am curiously surprised, because it suggests an energy and force of which we have no memorials.”

During the Colonial Revival of the early 20th century, Americans — particularly those well-off enough to reimagine the nation’s past as a series of idealized Currier and Ives lithographs — began to collect artifacts of that past, such as old farm tools, and to reconstruct early villages. People refurbished rural stone walls on properties that had been abandoned generations earlier.

It was American Poet Laureate Robert Frost, perhaps more than anyone else, who imbued New England’s stone walls with mythological significance. Frost’s poetry helped solidify the heroic, all-American image of the Yankee farmer — independent, self-reliant and resilient — standing up, defiantly, to the relentless stone. Thorson says that for Frost, “stone walls were more than symbols. They were oracles.”

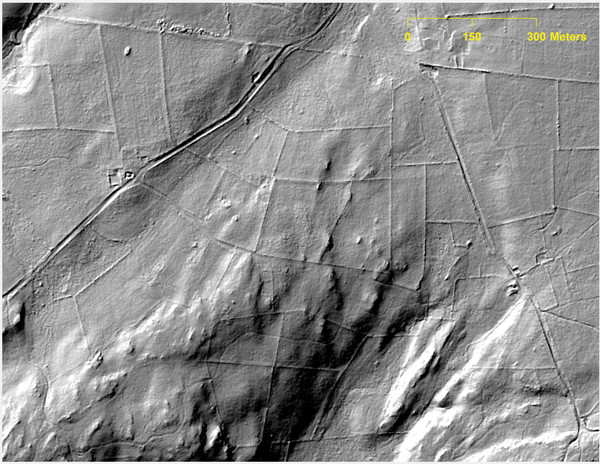

A lidar study by University of Connecticut geographers Katharine Johnson and William Ouimet revealed the remnants of a former "agropolis" of farm roads and fences hidden by new-growth forest. Credit: K. Johnson and W. Ouimet, J. Arch. Sci., 2014.

Through Frost and other writers and artists, Thorson says, New England “learned to love its stone walls more as memorials to a lost world than they had ever been loved as fences.” And with the growing appreciation of America’s heritage came an increasing understanding of the walls as actual ruins of early American civilization and the awesome human achievement they represent, he says.

A March 2014 study in the Journal of Archaeological Science offers a fascinating glimpse of what lies beneath the forests that now envelop many New England farms abandoned in the latter half of the 19th century.

Using a laser mapping technique called lidar that can see landscapes even through dense forest cover, University of Connecticut geographers Katharine Johnson and William Ouimet conducted aerial surveys of the heavily forested areas of three southern New England towns. The researchers found remnants of a former “agropolis,” vast networks of roads and stone walls that have been hidden for more than a century beneath the dense cover of oak and spruce trees.

Between lidar’s ability to pull back the biological curtain of the forest and Frost’s pulling back the psychological curtain drawn against the pain of abandonment, Thorson muses, it would seem that science and poetry together finally “allow us to actually see things that everyone knew were there all along.”

Through his work with the Stone Wall Initiative at the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History, Thorson says he intends to ensure that stone walls — New England’s iconic landform — will continue to be seen by many generations to come.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.