by Carey King Thursday, January 5, 2012

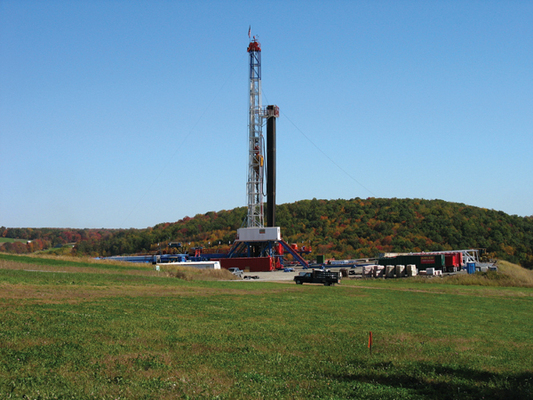

A vertical drilling rig in Pennsylvania extracts natural gas from the Marcellus Shale. Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection

Some people say fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is the mother of all evils whereas others say it's a necessary part of our energy salvation. Callan Bentley, 2011

In 2012, we should contemplate how much the period from 2002 to 2011 looked like 1973 to 1982. The earlier period, just a few decades ago, was marked by energy crises (instigated by global geopolitics). The U.S. had just ended a war that it couldn’t win; high energy prices threatened our ability to repay debts; the gold standard was abandoned, and the savings and loan crisis ended in many bank failures. Starting in the 1970s, we banded together and the energy crises brought about advances in energy efficiency, renewable technologies and the exploration for new oil and gas resources.

Today, we are in a global debt crisis. The U.S. has yet to fully remove itself from wars with no clear end; developed economies can’t grow while paying the going rates for oil and other energy sources (whether or not the rates are exacerbated by global geopolitics); and bank and debt defaults are likely not over. In 2012, will we begin to band together and bring about advances in society, and energy and economic policies? Possibly. But if 2011 is any indicator, cooperation is getting more difficult. But, of course, the future is inherently unpredictable.

Before we consider what will happen in the next year, we need to look at a couple of energy and economic fallacies that affected us last year (and for quite a few years) and that will likely continue through 2012.

First, there is the lack of recognition of the long-term role of the quantity and quality of energy resources in macroeconomic thinking and the rich world’s sluggish economic recovery. The ongoing trends, prices and usage of all natural resources, especially oil, must be reconsidered. Oil prices have fluctuated tremendously in the past 50 years, not to mention the last five. The fallacy is in thinking that oil prices will ever sink very low again: They won’t.

The reason that high oil prices are not temporary is that it’s not getting easier to extract oil and the oil is never going to be higher quality than it is right now — or than it was in the past. The shallow, high-quality oil has been recovered. This means we’re now harvesting or will harvest oil from oil sands in Alberta; from deepwater wells off Brazil, western Africa, and the U.S. Gulf coast; and from smaller or mature fields in the traditional oil-producing regions. In other words, the “energy return on investment” — the EROI, or the amount of energy harvested versus the amount that’s spent to collect it — is significantly lower for new marginal fuels versus the fuels from the conventional oil that we consumed during the last century. Biofuels and large reserves of unconventional oil exist (such as oil shale), but they are of low EROI.

Just as with low-content mineral ores, if the oil EROI is low, prices must rise to make production economical. This rise in production cost increases nonlinearly as EROI decreases. Furthermore, because the marginal benefit of energy consumption in developing markets is higher, those markets can consume energy at higher prices than developed economies. This means that if I give a dollar (or in this case an extra unit of energy) to a poor person (say, in China), there is more overall economic benefit to that poor person than the economic benefit of giving that extra dollar or unit of energy to a rich person (say, in the U.S.). That is to say, today’s marginal oil resources require higher prices, which emerging markets can afford more than advanced economies can.

And that brings me to the second and third energy fallacies perpetrated this year: Hydraulic fracturing — or fracking — is inherently bad, and natural gas from shale is a gift from above. Fracking, a way of producing natural gas and oil from tight shale formations, has been all over the news during the last year. It has been blamed for everything from ruining local water resources to inducing earthquakes. Depending upon your perspective, hydraulic fracturing is the mother of all evils or a necessary part of our energy salvation; it’s either going to ruin the environment (and your land value) or it’ll free us from the claws of OPEC. As usual, the truth is somewhere in the middle.

Fracking does consume a good deal of water: several million gallons of water for several billion cubic feet of natural gas. But the consumption rate is actually on par with the rest of the oil and gas industry and is on the low end of the water-intensity spectrum compared with other liquid or gaseous energy alternatives like biofuels. Locally the consumption can matter; globally it does not.

In terms of water quality, if done right, fracking does not affect water resources. However, if shale gas developers have poor well-completion practices (meaning they insufficiently protect aquifers from the well fluids), then by all means they should be held accountable for leaking any fracturing or produced fluids into underground sources of drinking water. But unless there has been an obvious well breakage or surface spill, tying fracturing practices to poor water quality is nearly impossible, and just finding methane in the water doesn’t cut it; methane can be there naturally. Poor quality water already exists in many areas, and a gas well nearby does not by itself prove causation.

Prediction for 2012: Lease owners will more routinely obtain baseline aquifer quality data before fracturing practices commence. Furthermore, there can be no doubt that this subject will be the subject of increasing scrutiny as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency begins to report from its ongoing study about impacts of fracking on water resources and aquifers.

Shale natural gas is also not clearly a panacea. There is an ongoing debate about the true size of the natural gas shale resource. For example, early estimates discuss the Marcellus Shale as having nearly 260 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable gas, but a newer estimate from the U.S. Geological Survey assesses a median estimate of 80 trillion cubic feet. This is a wide discrepancy for an anticipated large play. Thus, there are long-term economic uncertainties along with the regulatory and environmental uncertainty.

Once we’re past the fallacies, we get to the question of what we’re likely to see in 2012 — and what we should see. First and foremost, the concept of finite natural resources should be a focus of debt and fiscal debates in the industrialized countries. Alas, tragically, it will probably continue to be swept under the rug. Politicians will continually plan budgets for the anticipated return to past growth without contemplating the potential, but increasingly likely, reality that complexity and resource constraints might have caught up to us.

The Economist’s July 31, 2011, cover story noted that the EU and U.S. are “turning Japanese,” in that population demographics and slower technical progress no longer allow us to temporarily conquer the natural resource constraints of a finite world. In other words, if you have to import most of your natural resources and your population has more people retiring than entering the workforce, it gets increasingly difficult to pay back your debt.

U.S. politicians and economic officials repeatedly explain that we will not follow the “lost decade” of Japan because we know better. (“Lost decade” refers to the period of low growth in Japan after the country’s real estate bust a couple of decades ago, when economic growth stagnated and the government had to bail out banks.) Unfortunately, even though the U.S. has larger energy resources than Japan, there are reasons to think that the U.S. is simply a few decades behind in the same long-term cycle: The U.S. operates the same basic economic system as Japan and may have already experienced a lost decade over the past 10 years, as recent statistics on U.S. median income suggest. Japan, a highly advanced but resource-constrained country, is the dead canary in the coal mine for the existing economic growth paradigm based upon resource consumption.

The developed economies need to move on from thinking that they are simply going to snap out of this period of stagnation and prevent another recession without making some major changes in the use of energy and natural resources. Whether that will happen is another story. I recently read (and loved) the 2009 book “This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly” by Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff. It teaches us that it is very common for economies to overestimate future growth, overinvest, and then default in one way or another.

This boom and bust phenomenon has occurred for centuries. But on the time horizon of fossil-fueled civilization, biophysical economics tells us that sometime it will be different, in the sense that our continual buildup of industrial capital cannot continue indefinitely. If we borrow at too high of a rate from Mother Nature, such that her energy and ecosystem services no longer provide for us, there will be no “Troubled Earth Relief Program” (TERP) to bail us out.

Economic growth, in modern society, is largely the use of high-quality energy to dig up materials from the ground to turn them into widgets or burn them to run services with the goal of repeating the process. This fundamental process has not changed even though the steel manufacturing of the industrial revolution has been supplanted by the microchip fabs of our seemingly virtual 2.0 world. But without the energy resources of the planet, the virtual — and real — world will collapse in a blue screen of death.

We know too little about how our monetary returns on investment relate to our energy returns on investment. From fossil fuels to photovoltaics, it is their net energy that allows us to place the down payments on our future. One model tells us that at some point absolute growth will cease in a finite world because resource and environmental limitations will outpace our adjustments in efficiency. Another philosophy says we will never run short of the energy we need to order our lives with ever more complexity, because we’ll sufficiently develop new energy technologies and efficient ways to adjust.

Over the last decade, the net energy from our energy resources declined, mimicking the decline of the 1970s, and we overestimated our rate of progress. Unlike the 1970s, this recent net energy decline was not imposed by a quasi-political body such as OPEC, however. Now there is a debt we cannot understand how to repay because most economic models don’t contemplate the threshold effects that human and natural resource constraints impose on our current situation. The coming year is a good time to rethink the model: Mainstream economics and policies need to consider how the scarcity and lack of equivalent substitutability of many of Earth’s natural resources — in particular energy — are playing an increasingly influential role in our economy.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.