by Megan Sever Thursday, January 5, 2012

The North Anatolian Fault breaks into a complicated network of fault branches under the Marmara Sea, where it passes just 20 kilometers south of Istanbul. The new quake did not occur on the North Anatolian Fault. Tobias Hergert

Megan Sever is managing editor of EARTH and writes the Hazardous Living blog. Jim Sever

By Tuesday evening local time, close to 500 people have been confirmed dead and more than 1,300 injured following a major magnitude-7.2 earthquake that struck eastern Turkey on Sunday at 1:41 p.m. local time. Countless people are still trapped under debris after the shallow quake, only 20 kilometers deep, leveled at least 2,260 buildings in Van, Ercis and other cities and villages, according to news reports. Now, freezing temperatures and the possibility of snow on Wednesday bring new dangers to trapped victims and the thousands of people who are displaced and living in cars, tents and outside. Meanwhile, aftershocks, some as large as magnitude 6.0, have continued to shake the region.

Turkey is a very seismically active country. This quake was centered in mountainous eastern Turkey, where the Arabian Plate collides with the Eurasian Plate at a rate of 24 millimeters per year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The collision is responsible for building mountains from the Alps to the Himalayas, including the two mountain belts where the quake struck — the Zagros and the Alborz ranges (see geologist Chris Rowan’s excellent description on Highly Allochthonous). This plate collision has a long history of strong earthquakes. The last massive quake in this region was a magnitude-7.3 event in November 1976 that killed several thousand people. More recently, a magnitude-6.0 quake struck eastern Turkey in March 2010, killing about 50 people, and a 6.4 struck in 2003, killing 150 people and injuring 1,000.

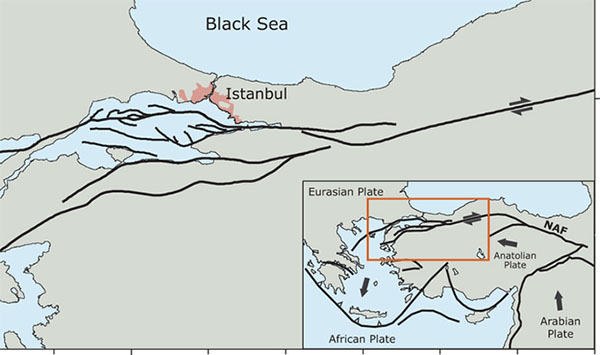

Despite producing such deadly quakes, the seismic activity in the eastern region of Turkey is largely overshadowed by the better-known North Anatolian Fault to the west, which runs 1,500 kilometers across northern Turkey, straight through Istanbul. This strike-slip fault was responsible for the magnitude-7.4 quake that struck Izmit in 1999, killing close to 20,000 people and injuring 50,000. A series of temblors has been striking along this fault, marching slowly and steadily westward with each quake rupturing a roughly adjacent stretch of fault. Some researchers suggest that the next major quake on this fault will strike Istanbul.

Given such seismic activity throughout this country, one would expect the government to mandate building codes and earthquake insurance. In fact, Turkey does have such a mandate, but as one news report shows, “compulsory” doesn’t mean enforced: Van province, for example, mandates earthquake insurance but only 9 percent of buildings are so insured. Most homes, let alone high-rise apartment buildings and office buildings, were not built to be seismically resistant. That means a lot of people are going to be out in the cold — literally.

Even though Turkey has had an earthquake early warning network in place since 2007 (as EARTH reported in October 2008), the network is centered on the North Anatolian Fault, too far west to have provided warning of Sunday’s quake.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.