by Essa L. Gross Thursday, January 5, 2012

Guatemalan teachers and John Lyons (left) conduct a workshop on earthquakes prior to conducting the first school-wide earthquake drill in locals schools near Fuego volcano. Courtesy of John Lyons

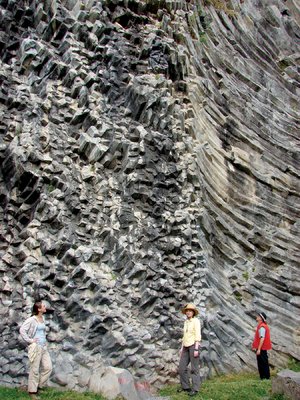

Peace Corps Master's International students Julie Herrick (left) and Karinne Knutsen and advisor Bill Rose (far right) examine an andesite lava flow from Volcán Baru in Panama. Courtesy of Julie Herrick

Jesse Silverman and several locals plant citaria grass as an erosion barrier in Tectitán, Guatemala. Courtesy of Jesse Silverman

York Lewis works with students in El Salvador to create a world map mural. Courtesy of York Lewis

At first glance, it seems like an obvious solution to a problem: Villagers need vegetables and an aid organization has money to buy tools and seeds. Striving to create a sustainable program, the aid organization develops a training plan to teach the villagers how to garden, invests in local workshops, and purchases tools to distribute to the participants. All plans seem in order and the project is poised for success. However, the project’s managers encounter the first of potentially many obstacles when they realize that shovels are impossible to use if you don’t have shoes.

This simple example illustrates the nearly ubiquitous problem of overcoming cultural barriers in development work. Solutions proposed by outside experts rarely work for the people they are trying to serve. Scientists and engineers who diligently work to find appropriate technical solutions to some of the most common problems encountered by the poor are frustrated at every turn — frustration fueled by misunderstandings and the failure to grasp basic concepts held by other cultures. Institutions investing in innovative approaches to international research and education hope to produce more culturally aware scientists — and this includes geoscientists. Difficulties borne from inadequate consideration of the social and cultural context are commonly encountered in geologic hazard mitigation and natural resource management.

Like much of the developed world, developing countries face potentially hazardous environmental problems. However, their circumstances place them at a distinct disadvantage to cope with disasters. The poor are more vulnerable, as many can afford only to live in high-risk areas such as floodplains, landslide-prone regions or near active volcanoes. They typically do not receive effective government support in the form of disaster relief or insurance, nor do they possess the economic resources to deal with natural catastrophes themselves. Federal and state institutional weaknesses may inhibit a region’s capacity to respond adequately.

Improper management and use of natural resources affect the poor to a greater degree than those who have the means to endure difficult times, such as in a drought. And finally, they may not have the tools to predict or work through natural hazards. Geologists can and should help. One avenue? The Peace Corps.

With the tools and ability to provide aid to at-risk populations, geologists also have a responsibility to assist communities in finding and managing water resources, adapting to changing climates and improving natural disaster mitigation. “Social geology” is perhaps the best term to describe this effort. One example of such efforts is Geólogos del Mundo (World Geologists), a European nongovernmental organization based in Spain that has worked in water resources and natural hazard mitigation in Latin America and Africa for 11 years. The program has also recently expanded into Southeast Asia. Two years ago, the Society of Exploration Geophysicists Foundation initiated Geoscientists Without Borders, whose projects focus on using geophysics and satellite-based remote sensing to ameliorate problems caused by water scarcity and earthquakes.

Yet another example is Michigan Tech’s Peace Corps Master’s International program in geosciences, with a focus on geohazards. It provides one way for geoscientists to utilize and enhance their training in the developing world.

The Peace Corps Master’s International program started in 1987; more than 50 universities now offer Peace Corps Master’s International programs in different disciplines. But only Michigan Tech offers a geosciences-focused program. Bill Rose, a volcanologist at Michigan Tech, started the school’s program in 2005. Several other faculty members also advise the master’s students in a range of topics from volcanic gas emissions to groundwater research. So far, five Peace Corps Master’s International students have graduated from Michigan Tech. Nine more students are currently serving in Latin America and Africa; three others have completed their service and are in the middle of thesis writing; and four are awaiting placement in the Peace Corps. “The Peace Corps association gives students an intense field experience that includes a strong social component, which grounds and guides our whole graduate research,” Rose says.

Typically it takes students three and a half years, including their Peace Corps service, to complete a master’s under the Peace Corps Master’s International program. An academic year of coursework prepares them for their research and their service as a Peace Corps volunteer. Students must define, design and carry out their research over the 27 months that they serve in the Peace Corps — worlds away from their university and advisors. Upon finishing their service, the students return to campus for at least one semester to write and defend their theses.

Working at field sites located thousands of kilometers from campus, the students must rely upon their own knowledge, problem-solving skills, adaptability and self-motivation. The added challenges of working independently in a foreign social and cultural context ultimately create a confident, culturally aware scientist with a grounded perspective of the complexities surrounding cross-cultural hazard mitigation and resource management.

Students choose either a scientific investigation that contributes to the body of geologic knowledge, like a traditional master’s project, or tackle a practical problem that the people in the field location are facing. The decision is usually made while in the field, with many factors influencing the formulation of a student’s research topic: the level of in-country support, community priorities and interest, volunteer interest and language capability, and accessibility to tools, land, maps and materials. In every case, aligning the right combination of variables requires patience and persistence.

“This program is challenging. It´s difficult to find a research project in conjunction with Peace Corps service, but taking on that challenge makes it even more meaningful,” says Rob Hegemann, a Peace Corps Master’s International student a year into his service in Honduras, where he is focusing on water quality. “I want to make a difference in my community and hope that my research will benefit the community members.”

So far, the Peace Corps Master’s International students at Michigan Tech have developed projects through collaborations with governmental agencies (such as the equivalent of the U.S. Geological Survey) and nongovernmental organizations. These collaborations enhance the potential for their work to directly aid in-country agencies. Additionally, Rose’s long history with the Central American institutions that work in volcanic hazards provides a valuable network for many students studying volcanic processes and natural hazard mitigation in that region.

Voices from the Field: Peace Corps Master's International students tell their stories

Statistically speaking, the program’s numbers are encouraging. Since the beginning of the program, about four Peace Corps Master’s International students have become Peace Corps volunteers each year and, on average, three have completed their service. In general, about 89 percent of Peace Corps volunteers finish their service. In this program, students who have terminated their Peace Corps service early have been able to adjust their research project and complete a traditional master’s degree. Of the program’s students to date, half are female.

Twenty-seven months of Peace Corps service more than doubles the typical time it takes to obtain a master’s degree through a conventional program. But from a purely research perspective, the extended field deployment provides the ability to collect data and make observations well beyond what is feasible in typical field studies. As residents of a field site, Peace Corps Master’s International students have the luxury of studying phenomena continuously in a manner that allows them to better observe seasonal effects or sporadic events — important for collecting data from multiple volcanic eruptions, for example.

Regardless of the research benefits that the program offers, however,

Peace Corps Master’s International students agree that one really must

want to be a Peace Corps volunteer first and foremost to succeed in the

program. Understandably, this type of program appeals to a particular

type of student: one who is independent, resourceful, adventurous,

persistent and patient. Most importantly, the student must accept the

ambiguity surrounding virtually everything — from things as simple as

an unfamiliar facial expression to accepting the months of uncertainty

waiting for a thesis project to evolve. With academic research always

simmering in the back of the mind, the student must first master the

language, get comfortable with cultural norms, and create a professional

support network. Only then will the student be able to decide how the

research will best serve the community. But whatever these students

choose, their service will last a lifetime.**

**

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.