by Mark Oscar McAdam Wednesday, April 11, 2018

If I only had one word to describe the new 10-part National Geographic documentary series “One Strange Rock,” produced by Darren Aronofsky and Jane Root, it would be “superlative.” But don’t misunderstand me: The series is not remarkable because it’s the best nature documentary I’ve ever seen. It’s not, although it does feature gorgeous footage and state-of-the-art, digitally generated animations, and perhaps covers a wider range of earth science topics than other documentaries in the genre. Instead, it is superlative in the way that Americans make many things superlative — with hyperbole.

In “One Strange Rock,” every fact and facet of nature is presented as utterly astounding. In the breathlessly titled first episode, “Gasp,” about Earth’s unique oxygen-enriched atmosphere, host Will Smith tells viewers: “I am going to tell you about the most incredible place … and you know what? You’re walking on it.” He later adds: “We’re walking a tightrope, with death on either side.”

In the second episode, titled “Storm,” Smith ominously intones: “Here comes the sun, it is the fuel of life. But it is not our friend. The sun is a planet-killer.” He also notes that “for 4.5 billion years our planet has been battered and bruised and punched and pummeled, but we’re still standing. It’s actually the battle that’s built us, and this is the tale of the tape,” Smith says.

Fans of David Attenborough’s calm dictation in the BBC documentary series “Planet Earth” may find Smith’s energetic sensationalism a little jarring. For me, though, the poetic and expressive language works. Smith’s excitement is palpable — a constant grin tugs at his mouth during interludes, shown in simple black and white filming, when he narrates directly to the camera. The same close-up, black-and-white aesthetic is used with the 10 astronaut presenters featured in the series — Chris Hadfield, Mae Jemison, Mike Massimino and Peggy Whitson, to name a few. An array of international geoscientists also takes part, helping narrate the episodes through voice-overs and on-location reports. Many of these scientists explain their work in their native languages, something not often seen in science documentaries produced in the U.S.

These moments of narration are useful devices, offering viewers momentary reprieves from the frenetic pace. After all, there’s a lot to take in, with stunning cinematography filmed across 45 countries and six continents as well as in outer space, where Italian astronaut Paolo Nespoli and NASA astronaut Whitson shot footage from the International Space Station.

National Geographic bills the 10-episode series — which began airing weekly on Nat Geo TV in late March (Episode 4, “Genesis,” airs Monday, Apr. 16) — as “an epic journey across the globe and into outer space” that “promises to be a thrilling, mind-bending trip within and beyond planet Earth, affirming that there really is no place like home.” To that end, the series focuses on the perspectives of those few humans who have left Earth and, having seen it from space, possess, we are told, more objective opinions about it. The astronauts’ experiences are contrasted with perspectives of earthbound humans, with footage cutting between views of Earth from space and views from the surface to reveal what is hidden from the astronaut’s viewpoint. These back-and-forth shifts are frequent in each episode, forming an interwoven storyline from different perspectives.

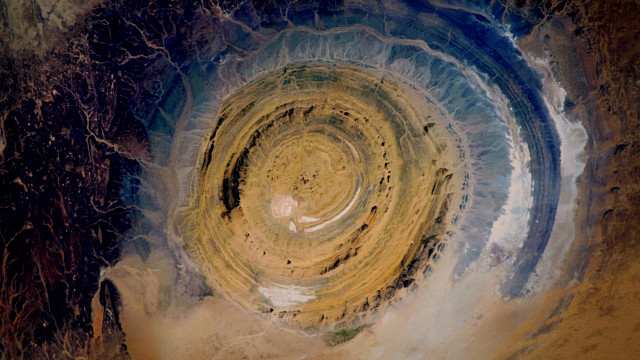

Some of the 45,000 photos that astronaut Chris Hadfield took about from space are featured in the first episode of "One Strange Rock." Credit: NASA

Throughout the series, Earth is portrayed as odd, rare, unique and special. It’s no wonder, since “strange” is right there in the title. This characterization allows the series to range over a plethora of issues, threading together what might seem like disparate topics into a coherent narrative. For example, the first episode begins with Will Smith playing with his dogs on Earth, which he notes is made possible by oxygen, then leaps to an interview with Hadfield about a scary incident he had during a spacewalk that necessitated having to evacuate the oxygen from his spacesuit. From there the show jumps to scientists dressed in protective suits collecting samples from an acidic lake occupied by oxygen-producing microbes that may have been similar to the early inhabitants of Earth.

That episode goes on to cover fumaroles, dust storms, diatoms, clouds, glaciers and why the atmosphere is blue, and juxtaposes these features and phenomena with the human experiences of astrobiologists, salt traders, climatologists, glaciologists and Buddhist monks.

I expected the second episode (“Storm”) to be about weather, but it soon became clear that the title refers to the space environment that Earth weathers. “Every day the Earth plows through about 40 tons of material in space,” astronaut Nicole Stott tells viewers.

“Storm” pings around the universe, touching on topics as diverse as asteroids and comets (including everything from dust particles to protoplanets), cenotes, deserts, circumstellar habitable zones, ice caves, frozen waterfalls, tides, Europa, and the Theia and Gaia hypotheses. Along the way we hear from free divers, Bedouin meteorite collectors, astrophysicists and Inuit elders.

The series focuses on the perspectives of those few humans who have left Earth and seen the planet from space. Credit: NASA

By dovetailing these various natural phenomena with diverse representations of humanity, the series shows that good science should also acknowledge its resultant philosophical implications. For example, “Gasp” addresses the notion that humanity takes for granted the unique conditions on Earth that have allowed humans to survive, and also that we often ignore that the spread of humans around the globe has constrained other species, shrinking their habitats and sometimes eliminating them altogether.

We are also shown that many scientific findings that the western world only recently accepted were intuited long ago by other cultures. In “Gasp,” Buddhist monk Pra Chayanon recounts: “All life is interconnected. Nothing exists in isolation.”

Ultimately, “One Strange Rock” is not so much about Earth itself as it is about how humans have managed to survive and thrive on a once inhospitable, and yes, very strange, planet. Perhaps that is something worthy of a little hyperbole.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.