by Anne Jefferson Wednesday, April 23, 2014

On a drought map of California for this past winter, the colors graded from yellow to deep red, indicating drought ranging from abnormally dry to exceptionally dry. The rest of the West is also dry, but the drought epicenter is California, where in January the governor declared an emergency and called for water use reductions to delay the nearly inevitable rationing to come.

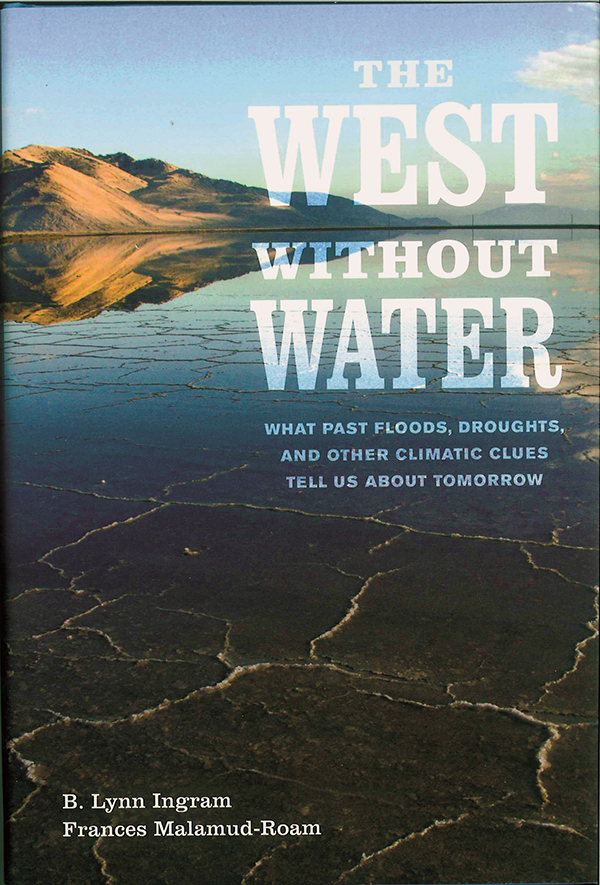

The drought impacted everything from wildfires to food prices across the country. Politicians and the media called this the worst drought in California history, but scientists know that intense multiyear droughts are a regular feature of California’s climate. Fortunately, B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam have put drought into context for everyone in their new history of California’s droughts and floods, “The West Without Water.”

The thesis of Ingram and Malamud-Roam’s book is that the historical (post-1850) climate of California has been relatively benign compared to what paleoclimate proxies indicate it was like over the last 10,000 years. The implication is that Californians would do well to bear the past in mind as they prepare for the future.

The book draws heavily on the paleoclimate research of the authors and their colleagues in the geography department at the University of California at Berkeley. Using mostly lake, wetland and seafloor sediment cores, they disentangle Holocene paleoclimate patterns from pollen, isotopes, charcoal and other proxy records. Although the book is titled “The West Without Water,” the focus is almost entirely on California and its hydroclimate.

The book begins with descriptions of the Dustbowl, the 1987–1992 drought and the 1861–1862 flood. The last swamped the Central Valley and left Sacramento under 3 meters of water. Here, the authors show their strength in deciphering clues from the past and combining them with up-to-date climate science, including how “atmospheric rivers” can cause catastrophic flooding in the state.

In the second part of the book, the authors explain basic paleoclimatologic techniques and then work their way methodically through Holocene climate intervals to show that megafloods and multidecadal droughts are a regular feature of the climate. I particularly liked that they also showed how human societies adapted, or didn’t, to the changing climate conditions.

In the book’s final section, the authors describe California’s engineered water supply and some of the climate model predictions for the 21st century. This section hits particularly hard given the current water shortages facing the state.

My one disappointment with the book was its narrow focus on California — Mono and Pyramid lakes are the farthest-inland features discussed — and the limited attention given to water and climate of the Intermountain West. The disappearance of the ancestral Pueblo culture is detailed, but the climate of the Southwest warrants only a paragraph.

It would be great to see a book that does for the broader western U.S. what Ingram and Malamud-Roam have done for California. Nevertheless, given California’s importance in our economy and culture and the intensity with which climate vagaries affect that state, “The West Without Water” is an important and timely addition to your library whether you live in California or not.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.