by Erik Klemetti Friday, October 13, 2017

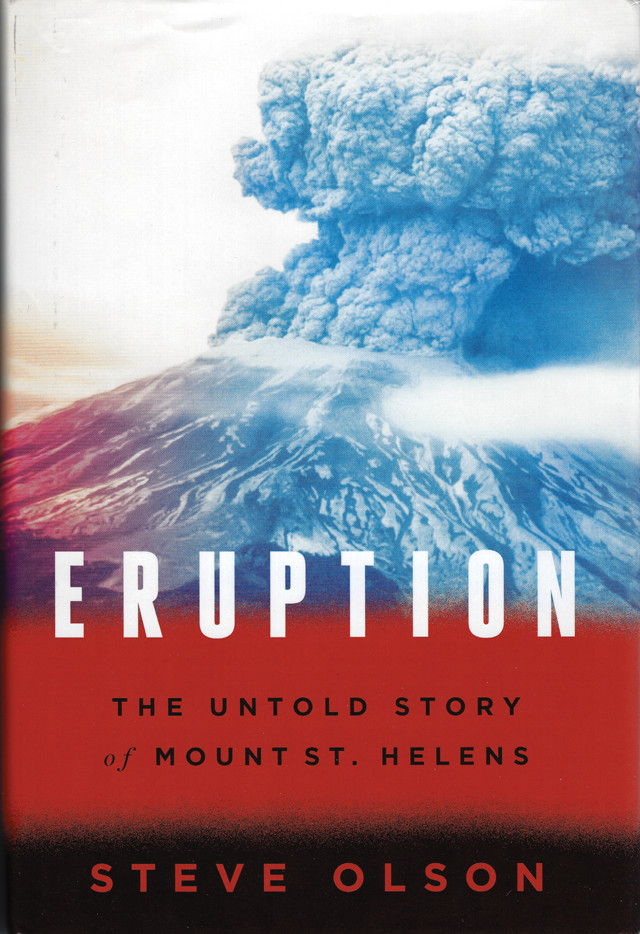

"Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens," Steve Olson, W. W. Norton & Company, 2017, ISBN-13: 978-0393353587.

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens was a pivotal event in the geologic careers of many volcanologists. Maybe it drove them to the geosciences, maybe it opened a door for more monitoring and research jobs in the United States, or maybe it was just an excellent example that the lower 48 states are volcanically active. However, as seminal as the 1980 eruption was, it happened almost 20 years before most of today’s college students were even born. To them, the eruption is another example from history, like Pelée or Vesuvius. They likely don’t have the same visceral reaction to it as those who remember it (even if, like me, you were still in preschool when the eruption occurred.)

The geologic tale of the eruption has been told countless times in print, on television and online. However, when it comes to breathing new life into what’s now a “historical” event to many, it is the story of the people who experienced it most closely — the narrative of the event — that grasps the imagination. This eruption was a game changer for volcano monitoring, but it was also an event that changed the people of the Pacific Northwest in ways that persist to this day. In “Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens,” Steve Olson tells the tale of these people that brings the event back to life after nearly 40 years, capturing the gut-wrenching emotions of those who survived the blast — and those who didn’t. It also digs deeply into the area’s rich local history — involving logging, conservation and geology — which is woven into the events of that spring.

For geologists, “Eruption” might feel light on the gory volcanic details. However, that’s not what this story is about. Instead, it offers firsthand accounts and evidence of the eruption. What did the volcano look like as it collapsed? What was it like to try to hike for your lives through falling ash? Or crawl from log to log out of a lahar? These are the visceral human stories not often conveyed in purely geologic retellings of the eruption, but they are the most vivid parts of the book. One brief sequence features geologists who had chartered a Cessna to fly around the volcano on the fateful Sunday. The description they gave of how the volcano broke apart — including the landslide at the beginning of the eruption — was jaw-dropping in its detail.

As a reader, you have to earn these firsthand accounts of the eruption to some degree. Olson places the story of the eruption in the context of the vital role that forestry played in developing the region. If your interests span volcanology and the birth of the conservation movement in the United States, you will not be disappointed. But it really isn’t until the second half of the book that the events of May 1980 on Mount St. Helens come to the fore. To get to this part of the story, you must read through a lot of the history of Weyerhaeuser, the logging company, and Gifford Pinchot, the founder of the U.S. Forest Service.

In Olson’s retelling, there are clearly heroes, villains and victims. Weyerhaeuser and Washington Governor Dixy Lee Ray fall into the second of these camps, portrayed as having stood in the way of a much broader closure, while U.S. Geological Survey volcanologists and the local sheriffs are painted in a more positive light for their efforts to inform the public of the hazard and to advocate for a much wider closure area than the roughly 30-kilometer evacuation zone that was finally settled upon.

One of the most fascinating examinations is of Harry R. Truman, the owner of a lodge on Spirit Lake who refused to leave and perished when a pyroclastic flow buried the lake and lodge. As Olson points out, Truman has become a mythical figure for stubbornly digging in his heels against leaving his lodge, which was within the evacuation zone. However, Olson brings out details to show how the media and governor played a hand in Truman’s unfortunate fate by making him into a hero for not bowing to calls to evacuate. Olson also dabbles in imagining how some of the volcano’s victims may have met their fate.

“Eruption” is clearly a book that exists because a lot of people who were there (many of whom are growing older) still have stories to tell. Where Olson’s book excels is in describing individuals who became enmeshed in the events: local residents, loggers, geologists, conservationists and survivors. Rather than merely telling us the details of the eruption and listing its impacts, Olson turns Mount St. Helens into a story of these people that culminates in the 1980 eruption that changed so many lives. And in that way, he brings back to life one of the most important eruptions in modern history for those who weren’t there — or even alive — when Mount St. Helens roared.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.