by John-Manuel Andriote Tuesday, March 3, 2015

"Walden's Shore: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science," by Robert M. Thorson, Harvard University Press, 2014, ISBN 9780674724785.

Last summer, I had the opportunity to enjoy a personal tour around the world’s most famous kettle pond, Walden Pond in Concord, Mass., led by geologist Robert Thorson, who recently authored the book “Walden’s Shore: Henry David Thoreau and Nineteenth-Century Science." The rainy, gray day did not diminish our hike or Thorson’s delight in sharing what he had learned from his research into Henry David Thoreau’s lifelong fascination with Walden Pond and the science behind his iconic book, “Walden.”

During the Quaternary Period, the Concord area was covered four times by thick sheets of glacial ice, and several previous versions of Walden likely existed between glaciations. The current Walden Pond formed when the last of those ice sheets retreated some 16,000 years ago, leaving a mass of glacial ice buried in a depression between two faults. As the ice melted, it formed a sinkhole that tapped into the water table, and filled up. Walden Pond isn’t fed or drained by streams, but is instead “basically a well,” Thorson says, replenished by groundwater — its unusually clear waters filtered through innumerable tons of sand and gravel.

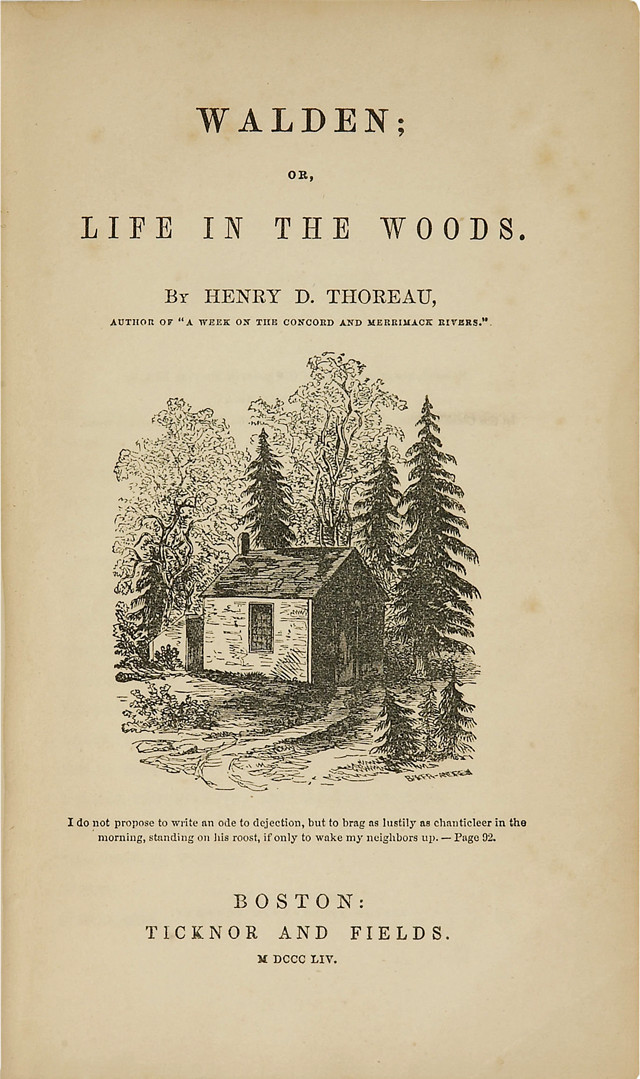

By the time Thoreau — who made his living as a land surveyor and pencil-maker — submitted his Walden manuscript, early in the spring of 1854, he had been visiting Walden Pond for more than 20 years, almost daily for the last 10 of those years. From 1845 to 1847, he had lived in his famous rustic house in the woods by the pond — built on land owned by his good friend and Concord neighbor Ralph Waldo Emerson — for “two years, two months, and two days.”

Thoreau tried to understand the world as he found it expressed in Concord’s surrounding forests and waterways, and nothing fascinated him more than the sources and seasonal cycles of Walden Pond. To better understand it, he read the work of the leading scientists of the day. Nothing shook up Thoreau’s thinking quite like the writings of Charles Darwin, including “Voyage of the Beagle” and “On the Origin of Species.”

In 1854, Henry David Thoreau published his account of communing with nature while he lived alone at Walden Pond for two years, two months and two days. Credit: Walden Woods Project.

Few recall that Darwin was primarily considered a geologist for his entire career before “On the Origin of Species” was published. Thoreau was drawn to Darwin’s work as strongly as he had previously been put off by local New England geologists. “He despised these ‘Men of Science’ — those wealthy enough to indulge their interest — because they were caught up in the Christian theories of creation and catastrophism,” Thorson says.

Under the influence of Darwin’s ideas, Thoreau began to think about the origins of life from non-life. “There is nothing inorganic,” he later wrote. “Surely, this is Walden’s most important line,” Thorson writes in “Walden’s Shore,” as he describes how Thoreau made the connection between geology and biology. “Thoreau’s insight regarding the origin of life and its corollary of continuous creation stood in diametric opposition to the ‘dead history’ of catastrophism, then the prevailing paradigm” he says. Thoreau “plainly saw” that Earth’s crust “was not the residue of something that has happened. It is the ultimate raw material for everything that is happening in the present moment. Ancient rock must be destroyed so that new rock can rise again.”

Eventually Thoreau’s pious neighbors condemned him as an atheist — and a heathen to boot — because his scientific exploration led him to conclusions that put him at odds with the prevailing Christian notions of the origins of Earth and humanity. For example, Edward Hitchcock, the state geologist of Massachusetts at the time, believed the New England landscape originated from tsunami-like floods from the Arctic, not from the action of ice sheets. “Thoreau wanted nothing to do with catastrophism,” Thorson says.

As Thoreau read the scientists’ books, his own way of thinking became more scientific. Biographers and scholars who study Thoreau have noted a shift in his written descriptions of natural phenomena, which progressed over time from metaphorical to literal. As a self-taught naturalist — a “good field scientist,” as Thorson puts it — Thoreau understood groundwater hydrology, ecology, meteorology, geology and limnology.

But Thoreau wasn’t content merely to understand why things worked as they do. “His purpose in Walden is to take us down all these branches of divergent complexity, including human spirituality,” writes Thorson.

Walden Pond in Concord, Mass. Credit: John-Manuel Andriote.

Thorson explains that the difference between Thoreau’s detailed scientific records and observations in his journals, and the ultimate book “Walden,” emerged from the way the writer processed his observations, a method that Thorson likens to threshing wheat. “Thoreau let the chaff of his scientific methodology blow away as the grains of literary truth fell to the threshing floor. At each step of refinement — notes, journal, lecture, essay, book — the scientific content of the text diminishes.”

This winnowing process in his writing, and in his beliefs, led Thoreau to a deeper, more refined and better articulated understanding of nature — and to a spirituality that couldn’t be contained in traditional religious concepts and images. For this reason, Thorson says Thoreau could be better understood as being “descendental”; “transcendental” suited him less well.

As a younger man, he says, Thoreau accepted “Emerson’s big idea that nature was a collection of natural facts awaiting correspondence with spiritual facts.” But as he moved toward the 1854 publication of “Walden,” the “transcendentalist” label no longer fit. Thorson describes Thoreau’s book as leading readers on a very different journey, “one that is descending inward toward the simplicity of a lower heaven in Walden’s waters, rather than ascending to an outward heaven.”

Or in Thoreau’s words — which Thorson uses as the epigraph of “Walden’s Shore” — “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.