by Jacob Haqq-Misra Friday, January 12, 2018

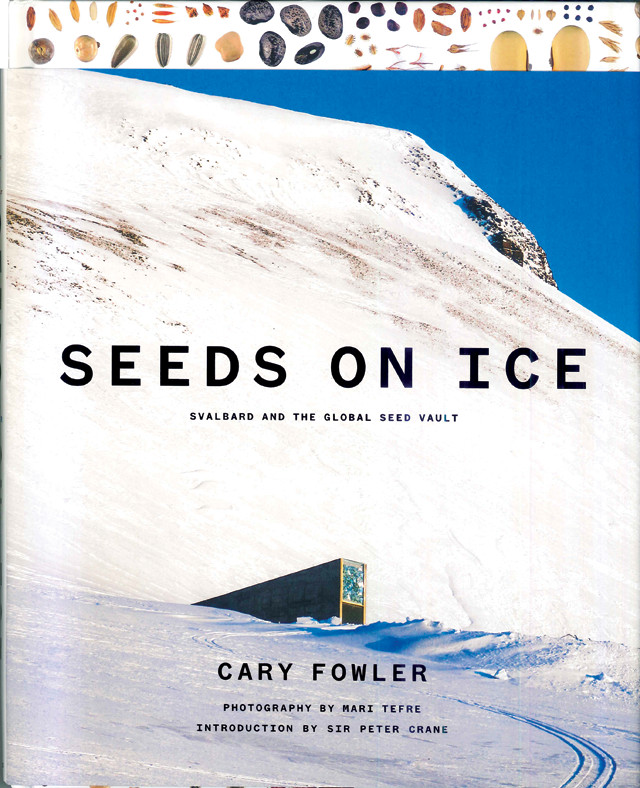

"Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault," Cary Fowler, Prospecta Press, 2016, ISBN: 9781632260574

“Tucked away, deep underground, in a frozen corner of the Scandinavian north is the safety net for our food supply. The Global Seed Vault, on the island of Spitsbergen in Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago and popularly known as the “doomsday vault,” shelters our most precious seeds from possible global catastrophe.

But such an extreme scenario was not the main consideration of the architects of the vault, including agriculturist Cary Fowler, author of “Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault." The real motivation for its construction was to protect against the steady and inevitable decline in the genetic diversity of our civilization’s agricultural crops brought about by insects, disease and changes in climate.

Humans have depended upon crop diversity — which is selected for through both harvesting and environmental pressures — since we first began practicing agriculture. And farmed cultivars constantly evolve: The wheat, beans, barley and other crops we eat today are considerably different than those consumed by the Romans, Egyptians and other ancient civilizations.

Small genetic changes in a particular crop can provide important survival benefits to the plant, perhaps allowing it to withstand a disease, insect infestation, drought or cold better than other crops. Cultivating multiple varieties provides protection against environmental pressures and ensures that at least some of these crops will survive to produce seeds for replanting.

Today, with more than 7 billion people to feed and emerging threats to agricultural biodiversity, the need to safeguard our food crops is more urgent than ever. The vault preserves the largest sampling of crop diversity from all parts of the world, including 200,000 varieties of rice and wheat; 30,000 varieties of corn, beans, and chickpeas; 20,000 varieties of millet; and 15,000 varieties of peanut.

Fowler provides a firsthand account of the vault’s backstory, along with a photojournalistic tour of the Svalbard archipelago and the people who made this unusual facility a reality. The book begins with a vivid depiction of the frigid Arctic landscape of glaciers and tundra. The full-color spreads by Norwegian photographer Mari Tefre in the first half of “Seeds on Ice” capture the beauty and isolation of a part of the world that most of us will never see. The photographic journey continues with a look inside the vault’s tunnels, storage and art, which only a few privileged dignitaries have been permitted to visit.

Fowler takes over the narrative in the second half of the book, detailing how he and his colleagues’ conception of a seed vault went from an idea in 2003 to reality with its opening in 2008. The $9 million construction bill was footed by the Norwegian government, the Nordic Genetic Resource Center and the Global Crop Diversity Trust, which continue to share annual operating costs of about $250,000.

Deposits to the vault are free. And any seeds deposited remain the property of the depositor, although they are logged in a database to ensure that every deposit is from a unique variety. Additionally, any gene bank, anywhere in the world, can access the vault to freely store and retrieve any agricultural seeds of value to its region.

Many agricultural gene banks exist around the world to protect regional crop diversity by providing seeds to researchers and other agriculturists to maintain healthy germination rates and guard against large-scale losses. However, Fowler and his colleagues noticed that practices at these various gene banks differed significantly, with many of them lacking the resources needed to effectively safeguard their seed stock. The Global Seed Vault thus serves as a “vault of vaults” to allow regional gene banks to safeguard their supplies.

Although the vault has been operational for less than a decade, there has already been one seed withdrawal. In 2015, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) requested the return of seeds that had been destroyed by fighting at their Syrian facility. More than 38,000 varieties of key crops were returned to ICARDA at their new headquarters in Morocco and Lebanon, where their agriculturists will reestablish gene banks for these species — and eventually send a new deposit to Svalbard.

“Seeds on Ice” is an inspiring illustrated tale of international unity, an example of nations working together for a better future. Let us hope that our knowledge of sustainability and efforts to reduce conflict will be enough to safeguard our food security. But if all else fails, at least we can rely upon the Svalbard Global Seed Vault to help us regrow.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.