by Abbey Nastan Thursday, May 26, 2016

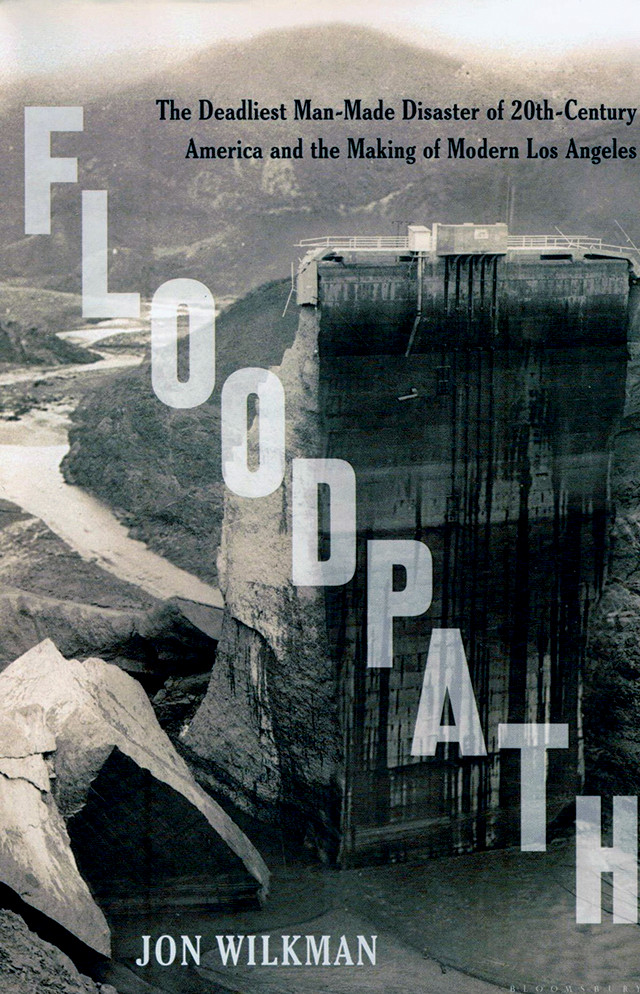

"Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th-Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles," by Jon Wilkman, Bloomsbury Press, 2016, ISBN-13: 978-1620409152.

The catastrophic collapse of the St. Francis Dam, located 80 kilometers north of downtown Los Angeles and east of the town of Santa Clarita, just before midnight on March 12, 1928, claimed more than 400 lives when towering floodwaters destroyed homes, bridges and farmland, as they swept through downstream communities. The disaster was initially blamed on the failure of the west abutment, anchored in soft conglomerate rock. Additional studies have revised this explanation, with recent research citing other geologic and design factors that likely contributed. Regardless, the collapse effectively ended the career of William Mulholland, the self-taught engineer whose 1913 Owens Valley Aqueduct made the explosive growth of Los Angeles possible. Yet, despite the magnitude of the disaster and its impact on local and national policy, it has been almost entirely forgotten, except by a few historians.

In “Floodpath: The Deadliest Man-Made Disaster of 20th-Century America and the Making of Modern Los Angeles,” author Jon Wilkman explores this little-known episode of California history and the decades-long efforts of scientists, engineers and historians to discover what really happened that night. Wilkman, an award-winning filmmaker who spent more than 20 years researching the disaster with his late wife and partner, Nancy, is currently working on a documentary as a follow-up to the book. He recently spoke with EARTH about his efforts to shed new light on the disaster.

AN: What was your goal in writing the book?

JW:__ My goal in writing the book was to take a surprisingly unknown story and put it in its proper historical significance and context; at the minimum, to honor those who had died and been forgotten. At the same time, it’s not just an old story. I wanted to engage people dramatically and intellectually to the point where they can apply what they learn in the book to issues that are quite vital today.

Concrete rubble from the St. Francis Dam can still be seen in the valley where it stood until failing on March 12, 1928. Credit: Abbey Nastan.

AN: What is the one piece of information that is most valuable for people to learn from the book?

JW:__ Science and technology do not exist in a vacuum separate from social, political, economic and personal factors. This may seem obvious, but so often people forget that, and the St. Francis Dam story is connected to the growth of the city, the rapid evolution of technology, the powerful personality of one man, the political and economic struggles over resources and water. All of those were factors in the technical mechanism of the collapse, beyond the forces of geology or an engineering failure.

AN: You grew up about 30 kilometers away from the ruins of the dam. But you say that it was never mentioned in school, is that right?

JW:__ I grew up in Los Angeles. It was never mentioned by anybody. This is a story with an enormous impact not only on Los Angeles, but California and the rest of the country. But few have heard of it. I began thinking: What really happened here? And even more of a mystery: Why don’t we know about it? This was the second biggest disaster in California after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. But this was a man-made disaster. So I just had to look into it.

[Researching the book] took a long, long time. Early on, I noticed that the people who had witnessed this were dying, so as early as 1995, I interviewed survivors and eyewitnesses. Some of them had never been asked what happened to them. I also realized that there was another layer of obscurity: I began, really for the first time, to interview some of the Mexican-American workers who had been personally affected by the catastrophe but had been largely overlooked in the intervening years. Many of them were young people, children at the time, but they remembered the flood.

AN: So, growing up, you had not heard about the St. Francis Dam, but did you learn about William Mulholland?

JW: Yes, I knew about him. I knew there was a Mulholland Drive and I knew there was a Mulholland Fountain, but even in high school, California history — certainly Los Angeles history — was not a big part of the curriculum. And most people didn’t miss it. The urban history of the West is only now beginning to be taken seriously.

AN: How did you first find out about the dam disaster?

JW:__ I read the book “Man-Made Disaster: The Story of St. Francis Dam” by Charles Outland [published in 1963]. Outland was a rancher, not a trained historian or engineer, yet he wrote this incredibly compelling and detailed historical and technical examination of the collapse.

AN: You researched the events surrounding the dam collapse over the course of 20 years. What do you feel you’ve added to the story that wasn’t covered by Outland or others who have written about it?

JW:__ I’m not an engineer, so technically I could only report what other people had discovered. What I wanted to add to it was the personal dimension, the political dimension, the economic dimension and the historical context. I thought as a historian and a storyteller I could take these events and put them in a broader context and engage people.

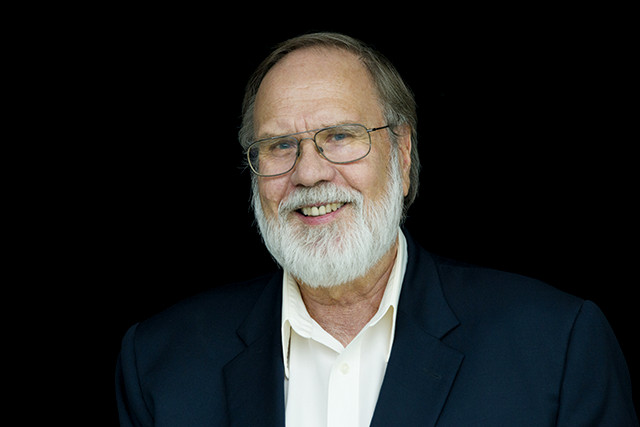

Documentary filmmaker and author of a book on the St. Francis Dam collapse Jon Wilkman. Credit: courtesy of Jon Wilkman.

AN: What sources, beyond Outland’s research, did you use in your book?

JW:__ One of the most critical pieces of information was the transcript of the [Los Angeles County] Coroner’s Inquest, which decided whether to issue criminal indictments. I think Outland had access to parts of the transcript, but it was pretty much considered lost, or buried somewhere where no one would ever find it. One day, my wife Nancy came home and said she’d found it in a very unlikely collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino. And there it was — all 800 pages.

William Mulholland’s granddaughter, Catherine Mulholland, also gave me three boxes of newspaper clips she had gathered for her biography of her grandfather. And another source that no one had looked at were the stories about the incident in Spanish-language newspapers, so we brought in a researcher to go through and translate. You get a whole different perspective.

Also, by the time we started working on our research, the archives of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power were starting to open up. Outland was sort of shut out of all that. One of the critical things was reports from the investigators who were involved in restitution efforts and who examined the dam site as part of the Coroner’s Inquest. So we ended up getting access to a lot of stuff that Outland didn’t have.

AN: Even today, the location of the former dam isn’t well marked on maps or on the ground. Would you like to see more commemoration of the disaster, or a memorial at the site?

JW:__ Absolutely. It is the worst man-made disaster of the 20th century in the U.S. The Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, a local congressman, the Native American community and others are pushing hard to have the location designated as a National Historic Site, but it’s been a long slog. I hope the book, by raising awareness of the importance of this disaster, will help it receive the recognition and the monument it deserves.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.