by Allison Mills Monday, June 9, 2014

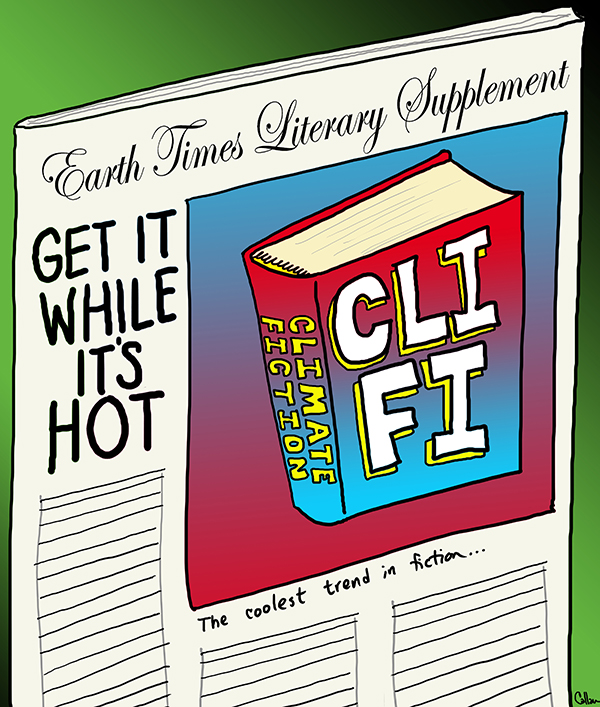

Cli-fi is a new genre. Credit: Callan Bentley.

The book cover of “Odds Against Tomorrow” (2013) by Nathaniel Rich features a flooded Manhattan. In a 2013 NPR story, Rich’s publicist, Brian Gittis, recounted how he left his waterlogged New York City office during Hurricane Sandy and came home to sort through advance copies of books, coming across Rich’s timely cover. Gittis called it a “Twilight Zone moment.”

Writers like Rich are crafting a new literary genre: climate-fiction, or cli-fi. Using climate science as a launching pad, these books, films, poetry and other media imagine life on a planet altered by human activity. The genre is still a niche but becoming more common as climate change has captured popular attention.

Some cli-fi is sci-fi, but not all. Jean McNeil’s “Ice Lovers” (2010) is an unlikely love story set in Antarctica. Michael Crichton’s “State of Fear” (2004) is a political thriller. Books like Barbara Kingsolver’s “Flight Behavior” (2012) explore people’s lives amid global change, while movies like “The Day After Tomorrow” (2004) blow it up on the big screen. (More titles can be found at Cli-Fi Books.)

Fictionalized climate clashes are not new. The nature versus humanity fight has deep roots in literature. What makes cli-fi new is the assumption that humans caused that conflict, says Gregers Andersen, a lecturer at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark who studies the genre. Sometimes nature fights back, and although the stories center on anthropogenic climate change as the fundamental tension, it’s the backdrop to human drama. Many cli-fi stories are apocalyptic tales set in the future.

“Because the apocalypse is entertaining, right? We’re fascinated with our own destruction,” Andersen says. The genre amplifies the drama of climate change to entertain and make a good story, but also to explore “our own predicament,” he says.

Fiction is a powerful tool to visualize what data alone can’t relay, Andersen notes. In his article “Cli-Fi: A short essay on its worlds and importance,” Andersen quotes French philosopher Paul Ricoeur: “The first way human beings attempt to understand and to master the ‘manifold’ of the practical field is to give themselves a fictive representation of it.” This link between science and fiction has a long friendship, Andersen says. Old sci-fi books and shows arguably inspired the design of modern technologies, just as Jules Verne’s books reflect science’s curiosity of realms unknown.

As a new genre, Andersen adds, cli-fi grapples with what many people have a hard time grasping: the extent of and possible destruction from climate change. He says that fiction is a way for people to try to understand what’s happening in the world. (Read more in Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow’s “Cli-fi: Birth of a Genre.”)

But fiction is still fabrication. Andersen notes it can stretch, tease or make up the facts because the freedom of fiction untethers it from the actual research and observation. So, while science has tossed out the fanciful ideas in Verne’s 1864 novel “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” popular imagination has not stopped reimagining Earth’s core in very un-scientific ways. (Consider the giant amethyst crystals in the movie “The Core” from 2003.) The risk then with cli-fi is that the portrayal of climate change may differ — and differ greatly — from reality.

Andersen says imagining what the world could be like is important, even if it’s not a perfect replica of reality. Fiction is like trying to see the back of your head with a mirror; fiction can explore and reflect what is not easily viewed. Cli-fi holds a mirror to the human experience of climate change and allows people to “look critically at ourselves,” he says.

“It’s about people living the torment of climate change,” says Andersen, explaining that he hopes cli-fi might encourage people to take action and “imagine the world anew.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.