by Julia Rosen Monday, February 1, 2016

A new app uses smartphones to detect cosmic rays. Credit: Crayfis.io.

At a time when the technical and computing capabilities of science are evolving at breakneck speeds, it might seem like researchers would always seek out more powerful and sophisticated tools to tackle their scientific questions. But some have chosen the opposite strategy: drawing on the dispersed resource of millions of relatively low-tech devices like smartphones and personal computers — and their users.

Researchers are turning to crowd-sourcing to study a wide range of topics, from cosmic rays to coastal erosion. So, the next time you find your brain — or your smartphone — sitting idle, consider opening up one of these geo-apps and performing a little citizen science.

Particles from outer space — mostly protons and alpha particles — rain down on Earth all the time. But astronomers still don’t know the source of the most energetic class of these particles, known as ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. Some think they may stream out of active galactic nuclei, while others say that they are produced by colliding galaxies or other cosmic processes. The problem is that researchers haven’t spotted enough of these rare particles to determine their origins. And at the moment, building substantially bigger detectors, like the $270-million IceCube neutrino observatory in Antarctica, isn’t an option.

However, a group of researchers led by Daniel Whiteson and Michael Mulhearn at the University of California, at Irvine and Davis, respectively, realized that about 1.5 billion small cosmic-ray detectors are already scattered around the world, and one is probably in your pocket right now: smartphones. Although your phone can’t detect cosmic rays directly, a chip in the camera can register photons and muons, which are produced when high-energy cosmic rays hit molecules in the atmosphere.

So, the researchers created an app called CRAYFIS (Cosmic Rays Found in Smartphones), which turns your phone into a particle detector whenever it’s not in use. The app is still under development, but already users in about two dozen countries have detected more than 23 million possible muon hits. The scientists told NPR that they don’t yet know if the app “is the best idea we ever had, or the silliest,” but if you want to help them find out, go to crayfis.io and sign up. You could be thanked in the acknowledgments section of an astrophysics paper, or perhaps even be a co-author.

A U.S. Geological Survey app called iCoast enlists users to spot and tag coastline changes after extreme storms, like Hurricane Sandy, which devastated parts of the New Jersey coast in October 2012. Credit: USGS.

Remember those spot-the-difference games popular in many childhood magazines? The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has developed a version for grown-ups that will also help the agency track storm damage and improve its coastal erosion models. The app, called iCoast, simply requires access to the Web, a few minutes of free time and keen attention to detail.

After you log in through the USGS website, the app presents you with photos taken before and after a storm along a section of coast from the eastern seaboard or the Gulf of Mexico. The program guides you through a series of questions to determine, for instance, if the storm washed away structures, destroyed dunes, or deposited new sand. Spotting the differences can be a little tricky — apparently too tricky for computers to do automatically, according to principal investigator Sophia Liu.

Liu and her partners launched the program in the spring of 2014, and within a year, users had classified nearly 8,000 sets of photos documenting the effects of Hurricane Sandy. However, the researchers still need help; the greater the number of different users who view and classify the photos, the better the results and the models will be.

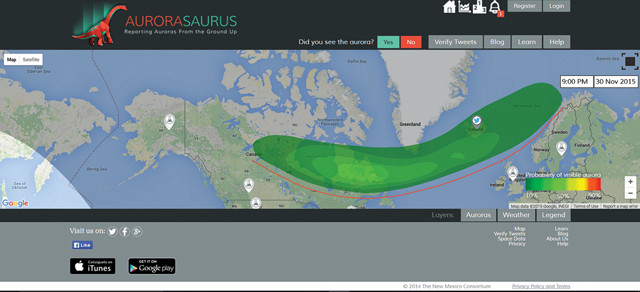

Aurorasaurus provides real-time predictions of auroral activity laid out on an easy-to-navigate map of the world. Credit: Aurorasurus.org.

If you plan to go hunting for the Northern Lights, you’d be well advised to sign up for Aurorasaurus. The app, developed by Elizabeth MacDonald of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and her colleagues, provides real-time predictions of auroral activity laid out on an easy-to-navigate map of the world. The app will also alert you when your area is in for aurorae and displays the current cloud cover, so you can decide whether it’s worth getting out of bed in the middle of the night.

In addition to the spatial data, the site contains a blog and educational material about aurorae, including what controls their appearance and how to photograph them. The best feature, however, is a real-time graph of the strength of the solar wind, which influences the intensity of the display. It’s a little hard to find — click the graph symbol in the upper right-hand corner of the website — but it’s extremely useful for those who want to dig into the details.

Aurorasaurus also keeps track of aurora sightings to improve predictions. These sightings are reported by registered users (of which there are already more than 1,500) or pulled from Twitter automatically. Any tweet containing the word “aurora” shows up on the map in the location where it was posted, and Aurorasaurus users nearby are asked to verify whether it’s really a sighting (most are not). If you like a little friendly competition, registered users can rack up points by reporting sightings and sifting through unverified tweets.

Researchers looking for a way to expand streamflow monitoring in upstate New York installed streamgages and posted signs asking passersby to text them the water height. Credit: CrowdHydrology/University at Buffalo.

CrowdHydrology was launched in 2010 by Chris Lowry of the University at Buffalo and Mike Fienen of USGS with the aim of expanding streamflow monitoring in Upstate New York using text messages. Instead of installing and maintaining a suite of expensive instruments, the team placed tall measuring sticks in stream channels and asked people to text them the water height whenever they passed by.

The initial results based on a few test sites were encouraging, according to a 2012 paper authored by Lowry and Fienen. Crowd-sourced data matched automated measurements fairly well, although — unsurprisingly — there weren’t many reports texted during storms, meaning some peak runoff events were missed. And while the researchers tried to place measuring stations in popular recreational spots, different sites saw dramatically different levels of crowd participation, showing that a few dedicated users can make a huge difference.

At the moment, most of CrowdHydrology’s sites are in the Great Lakes region. However, the scientists also have one streamgage in Provo, Utah, and another in Corvallis, Ore., and they say they are looking to expand. But no matter where you live, you can use their freely available data. On the CrowdHydrology website, you can choose any monitoring location and access water level data over a given window of time. There’s a widget that allows you to graph the data online, or you can download them for future use.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.