by Terri Cook Thursday, December 11, 2014

The first time filmmaker Peter Jackson read J.R.R. Tolkien, he was 18 years old and riding a train across the North Island of his native New Zealand. Whenever Jackson glanced out the train’s window, he was struck by how much the passing landscape resembled his imagined picture of Tolkien’s mythical realm of Middle-earth. This revelation stuck with him; two decades later, Jackson chose New Zealand as the backdrop for his blockbuster film adaptation of the entire “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy, and again later when filming “The Hobbit” series.

This landscape — with its vaguely familiar, yet primeval feeling — was integral to creating the atmosphere and evoking the emotion of Tolkien’s fabled world set 6,000 years ago on Earth. Who can forget Aragorn galloping toward the isolated, windswept grandeur of Edoras, the capital of the Kingdom of Rohan, or an exhausted Frodo Baggins stumbling across the dark, threatening moonscape of Mordor? Thanks to Jackson and his production team, Tolkien’s Middle-earth will forever be associated with New Zealand’s breathtaking landscapes.

Just as enthralling as Tolkien’s mythical prehistory is another, considerably longer epic tale of the geology of this landscape, which formed over hundreds of millions of years.

Since the release of “The Fellowship of the Ring” in 2001, millions of tourists have flocked to the Southern Hemisphere to see “The Lord of the Rings” movie backdrops for themselves. As an avid Tolkien fan, I too wished to follow in the Hobbits’ hairy footsteps and visit a few of the key filming locations while also learning more about the formation of the “real” Middle-earth.

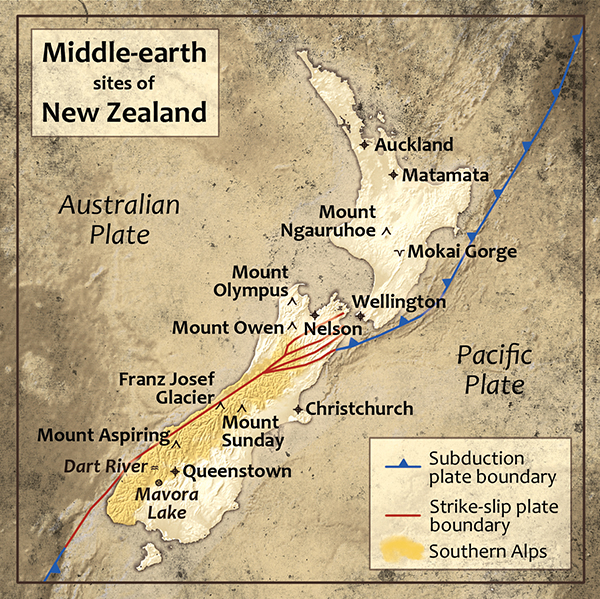

Locations of some of the 100 filming sites in New Zealand that stood in for mythical Middle-Earth locales in "The Lord of the Rings" movies. Credit: Kathleen Cantner, AGI.

Much of Middle-earth’s natural history is interwoven with the story of Gondwanaland, the southern part of Pangaea, which broke away about 200 million years ago. The supercontinent of Gondwanaland included most of modern-day Africa, India, South America, Antarctica, Australia and New Zealand. The bulk of New Zealand’s landmass was formed along Gondwanaland’s east coast where, over millions of years, ash belched by offshore volcanoes and thick piles of sediment deposited by rivers draining the continent’s interior accumulated in the sea. Repeated mountain-building episodes uplifted and plastered these new rocks onto the edge of the expanding supercontinent.

As Gondwanaland subsequently broke apart, the mostly submerged micro-continent of Zealandia, of which New Zealand is a small part, began to rift away from Australia and Antarctica about 85 million years ago. New Zealand has endured noteworthy isolation ever since, resulting in the evolution of a unique fauna and flora, including species descended from ancient Gondwanan ancestors in the country’s dense temperate rainforests, which endow the countryside — and Jackson’s Middle-earth — with its primeval feeling.

Today the inexorable forces of plate tectonics are still sculpting New Zealand’s landscape, forging the fabulously diverse scenery that Jackson harnessed to recreate the various moods and geographies of Middle-earth. Such great diversity over an area about the size of Colorado is the direct result of New Zealand’s modern position straddling the boundary between two major tectonic plates, the Australian and the Pacific.

In the current configuration, New Zealand’s North Island rests entirely on the Australian Plate and hosts many volcanic features — including steaming hot springs, geysers, and a chain of active volcanoes such as Ngauruhoe, the model for Mount Doom — created by the subduction of the Pacific Plate off the island’s east coast. In contrast, most of the South Island lies on the Pacific Plate. Here, the plate boundary runs along the island’s west coast and is defined by a major strike-slip fault, the Alpine Fault. There is also compression along this boundary that is uplifting the Southern Alps, the breathtaking stand-in for Tolkien’s Misty Mountains.

All three “The Lord of the Rings” movies were filmed simultaneously, an unusual step for live-action filmmaking. From the beginning Jackson and producer Barrie Osborne committed to filming in the best — rather than the easiest — locations, according to “‘The Lord of the Rings’ Location Guidebook” by Ian Brodie.

Selecting the filming sites for the $280 million production was a long and meticulous process. First, a team delved deeply into Tolkien’s vivid descriptions, assembling lists of the attributes their filming locations must have to recreate each Middle-earth locale. Conceptual artists then transformed Tolkien’s eloquent words into detailed drawings, which scouts carried into the bush, crisscrossing the country to identify matching sites.

After this initial sweep, Jackson and Osborne led a team to visit each potential locale, questioning first and foremost if the locations matched Tolkien’s descriptions. They also examined logistical challenges posed by each area before settling on sites. This proe beginning of a monumental effort; the production ultimately involved more than 100 locations, 300 sets and 2,500 cast and crew members spread across the two islands.

Many of the most memorable scenes from “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy were filmed amid the South Island’s Southern Alps, where compression along the Alpine Fault is actively uplifting ancient basement rocks, predominantly dark greywacke sandstone, plus schist, gneiss and granite.

In the films, the Southern Alps stand in for the Misty Mountains, Middle-earth’s lofty, snow-capped range toweri, grassy plains. In Tolkien’s mythology, the 1,500-kilometer-long range was uplifted in the First Age and contained Middle-earth’s highest peaks, including Caradhopes the struggling Fellowship tried to cross the divide. The orographic lift and ensuing clouds and precipitation created by strong westerly winds gave the mythical mountains their name, and the same conditions prevail in the real Southern Alps today, which posed many challenges during the filming.

The Misty Mountains’ spectacular peaks are featured in the opening sequence of the second movie, “The Two Towers,” filmed near the real Mount Aspiring, and in the Lighting of the Beacons in the third film, “The Return of the King.” During this succession of igniting mountain-top flares, you can see some of the Southern Alps’ dark basement rocks. These scenes were filmed near the real Mount Gunn in Westland National Park near the heavily crevassed Franz Josef Glacier. For Tolkien fans with deep pockets, both of these filming areas are accessible via special helicopter tours.

One of the trilogy’s most poignant scenes occurs in the mythical Dimrill Dale, a valley on the eastern side of the Misty Mountains, where the Fellowship mourns the death of their companion, the wizard Gandalf. The characters’ heartbroken expressions and the Hobbits’ forlorn sobs seem to be amplified by the surrounding stark, white, pockmarked landscape — a great example of how Jackson and his team used New Zealand’s geology to enhance the emotion of a scene. Jackson often filmed the same scene in multiple locations and spliced the results together to create the perfect ambience — albeit at the cost of geologic congruity.

The upper Dimrill Dale, for example, was filmed on Mount Owen in the South Island’s Kahurangi National Park, located west of the city of Nelson. This area, part of the small chunk of the Australian Plate on the island’s northwestern corner, is locally capped with Ordovician white marble, which rainwater has partially dissolved, gradually enlarging fractures and cavities. Continued dissolution has produced karst, the distinctive, pitted topography full of sinkholes apparent in this scene. Yet seconds later, as Aragorn leads the group down the valley, he runs through a stream surrounded by talus piles of dark, angular rocks. This portion of Dimrill Dale looks completely different, and for good reason: Instead of white marble, it features dark schist that’s found on a different tectonic plate. These scenes were captured at the real Lake Alta above the Remarkables Ski Field near Queenstown, about 500 kilometers to the south.

The 110-million-year-old granite spires of Mount Olympus provided one of the most distinctive backdrops in the trilogy. Credit: ©iStockphoto.com/HowardPerry.

Two other sites in the Nelson area were also used in “The Fellowship of the Ring.” The first was Takaka Hill — which is located not far from Harwood’s Hole, the largest sinkhole in the Southern Hemisphere — which stands in for a grass-covered limestone plateau near the wilderness of Chetwood Forest, where Aragorn led the Hobbits after they left Bree.

The second was Mount Olympus, a mid-Cretaceous granite pluton that Jackson used to portray some of the rough country to the south of the mythical Elven city of Rivendell. Here among spectacular real-life 110-million-year-old granite spires, the Fellowship hid from Saruman’s spying black crows. Part of a series of four plutons, this granite is the root of an ancient volcanic arc created by subduction along the edge of Gondwanaland while New Zealand was still attached. The granite was later added to the landmass during a violent mountain-building collision.

The town of Nelson, renowned for both its sunshine and its artisans, is where the props department for the “The Lord of the Rings” procured many important articles, including 50 copies of the One Ring crafted by silversmith Jens Hansen and his son, Thorkild. One of the originals is still on display at their shop (where visitors can buy a replica of their own in 9- or 18-karat gold).

Tolkien fans who, like a Hobbit, are always ready to eat a “second breakfast” or drink a pint of ale should be sure to visit nearby Harrington’s Breweries, who concocted a special stout beer that was served at the pubs in the Tolkien towns of Hobbiton (Matamata) and Bree during filming. Because of the number of takes required to shoot scenes, the ale’s alcohol content was limited to 1.1 percent. Happily the brewers also created a more potent version for visitors who, like Merry and Pippin, like to sing and dance on the tables.

More than 2,000 kilometers long and flowing parallel to the Misty Mountains, the Anduin is the longest river in Middle-earth. After leaving the peaceful forest of Lothlórien, the Fellowship followed the Anduin’s course for days, paddling Elven boats nearly 500 kilometers down the river’s iridescent blue waters.

In “The Fellowship of the Ring,” Jackson’s version of the Anduin was a composite of four different rivers that collectively highlight New Zealand’s scenic and geologic diversity. The impressive 80-meter-deep Mokai Gorge on the North Island’s Rangitikei River, near Taihape, was the first to appear on screen. Additional shots were filmed on one of its tributaries, the fern-draped Moawhango River. In the Wellington area of the North Island, close-up footage of the Fellowship paddling their boats was filmed on the beautiful Hutt River.

The Hutt River follows the trace of the active Wellington Fault, a predominantly strike-slip feature that runs along the west side of Wellington’s harbor (itself a volcanic caldera) and forms Hutt Valley’s unusually straight western edge. In 1855, a major earthquake on the nearby Wairarapa Fault raised the level of both the riverbed and the valley, draining the surrounding wetlands and leaving the previously navigable river impassable.

On the South Island, additional River Anduin scenes were filmed on the Wairau River, which flows between two beautiful lakes that formed in deep, glacially carved valleys blocked by terminal moraines. The brilliant turquoise color of this river, so stunning on screen, is due to the presence of glacial flour, fine powdered rock ground by glaciers, suspended in the water column.

The background for the Argonath — the soaring Pillars of the Kings that the Fellowship passes near the end of their voyage down the Anduin — was also filmed on the South Island, on the Kawarau River close to Queenstown. Although the Argonath’s pillars were computer generated, the background is easily recognizable. Devoted Tolkien fans can further immerse themselves in Middle-earth by rafting past the Argonath backdrop on a trip with Extreme Green Rafting, one of the companies that assisted Jackson with filming.

After the Fellowship gazed upon the Argonath, they entered Nen Hithoel, a large lake pooled above the crashing Falls of Rauros where the Fellowship waited for darkness to cross the lake. The scenes along the shore were filmed southwest of Queenstown at North Mavora Lake, the sparkling blue waters of which are nestled among steep, tree-studded slopes. Based on the different metamorphic rock assemblages on either side of the lakes, geologists have concluded that a major fault runs through the center of the North and South Mavora Lakes, creating a depression in which the water has pooled. Some of the hills west of the lakes contain distinctive slivers of ophiolite — ultramafic oceanic crust — that formed during the Early Permian and were added to the edge of Gondwanaland’s overriding continental crust during subduction about 250 million years ago. The presence of similar rocks nearly 500 kilometers to the north helped geologists recognize and measure the displacement that has occurred along the Alpine Fault.

In Middle-earth, Mordor is a desolate and barren land blocked by mountains on three sides and occupied by Sauron for thousands of years during the Second Age. Within this wasteland looms Mount Doom, the volcano where the Dark Lord forged the One Ring, and his imposing fortress of Barad-dûr. The eruptions of Mount Doom are controlled by Sauron, whose power extends into its incandescent fires. Lying dormant while Sauron is away and springing to life as his power grows through the trilogy, Mount Doom is, geologically, a most unusual volcano to say the least.

In the movies, Jackson filmed key scenes from Mordor in the North Island’s Tongariro National Park, skillfully using its dark, jagged volcanic rocks to evoke a mooand despair. The park encompasses the Tongariro volcanic center, a complex of andesitic stratovolcanoes built up, eruption by eruption, over the last 275,000 years. Dubbed “the forges of Middle-earth” by the Geological Society of New Zealand in its book “A Continent on the Move,” these cones comprise the southern end of the Taupo Volcanic Zone, the long chain of andesitic volcanoes created by the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Australian Plate to the east of the North Island. The most infamous of this chain is Taupo, a supervolcano that produced the largest eruption to occur in the last 70,000 years.

Various parts of the park’s spectacular scenery doubled as important Middle-earth locales, most notably Mount Doom, which was modeled after the classically shaped volcanic cone of Mount Ngauruhoe. Only about 2,500 years old, Ngauruhoe most recently erupted in 1975. Variations in the chemistry of lava at Ngauruhoe indicate that its magma forms in small batches within a complex and rapidly changing subterranean plumbing system. Erupted lava also often contains fragments of partially melted sedimentary and metamorphic rocks torn from the underlying continental crust during the magma’s ascent, providing geologists with a window into New Zealand’s basement. Because Ngauruhoe’s summit is sacred to the local Māori, Jackson wasn’t allowed to film it directly, so he used a model and special effects to portray the peak in wide-angle shots.

Part of the same volcanic center, Mount Ruapehu, New Zealand’s largest active volcano, is composed of roughly 100 cubic kilometers of material ejected over its 230,000-year-history. Ruapehu’s most recent eruptions include minor events in 2006 and 2007 and a more spectacular explosion in 1995–1996, which lasted for several months and had an estimated $110 million impact on the North Island’s alpine tourism industry. Based on a study of ejected materials on the plains downwind of the volcano, geologists think that eruptions comparable to the 1995–1996 episode have occurred about once a century at Ruapehu for the last 2,000 years.

Many scenes in or near Mordor — including the Battle of the Last Alliance, the capture of Gollum by Frodo and Sam, and the wandering of the lost Hobbits through the labyrinthine Emyn Muil — were filmed near the Whakapapa Ski Field on Ruapehu’s northwestern slopes.

Just as the North Island’s geologically young volcanoes have played an important role in creating its modern appearance, glaciers have placed many of the finishing touches on the South Island’s beautiful landscape. The ruggedness of the mountains, the deep glacial lakes and the broad, U-shaped valleys were fashioned by these powerful sculptors. This glacial scenery is especially evident at two crucial Middle-earth locations: the Wizard’s Vale, where Saruman’s fortress of Isengard was located, and Rohan’s capital of Edoras.

In the movies, Isengard was a visual composite based on aerial footage of the U-shaped glacial Dart River Valley, located near the start of New Zealand’s famous Routeburn hiking track, although the river was digitally removed. Edoras was filmed at an impressive set built atop Mount Sunday, a rocky knoll located in the stunning Rangatita River Valley high above the Canterbury Plains. During the last ice age, which ended in New Zealand 11,500 years ago, this area resisted the erosion that carved out the surrounding land, leaving behind a bare hillock whose sheer sides now overlook braided river channels and windswept tussocks against a backdrop of steep, snow-capped mountains.

Because of the unpredictable weather in this remote alpine valley, Jackson’s crews needed almost a year to build the set, which was dominated by Meduseld, the King’s golden hall. Although the set was removed after filming, the sounds of the mustering Rohirrim and the raucous feasts in the golden hall still seem to echo across the raw, untouched beauty of this remote and breathtaking setting.

After visiting many of the filming sites and learning more about how these diverse landscapes formed, watching the movies is even more entertaining because I can recall my own Middle-earth adventures hiking near Mount Doom, trying on the One Ring and paddling down the brilliant River Anduin. As actor Elijah Wood, who starred as Frodo, famously said, “New Zealand is Middle-earth.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.