by Christopher L. Atchison and Brett H. Gilley Thursday, August 6, 2015

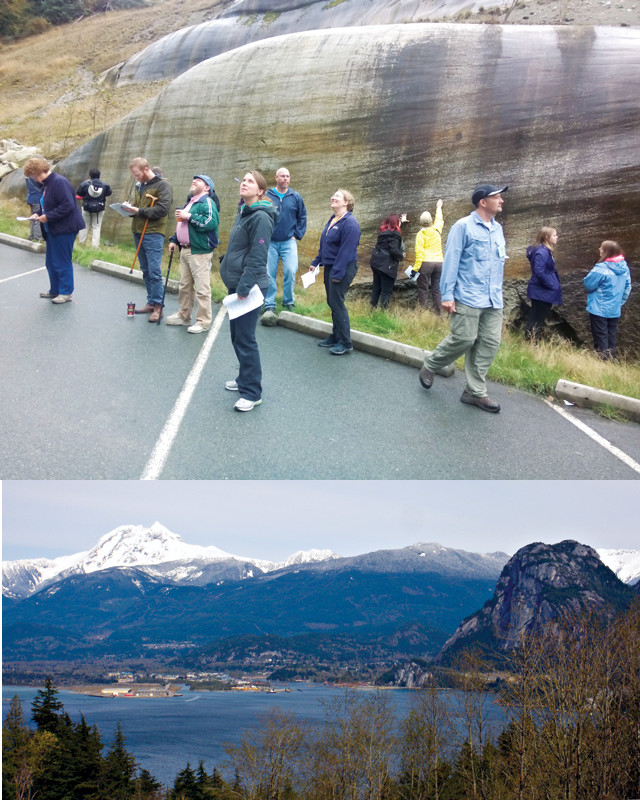

The design of this field trip at last year's Geological Society of America meeting in British Columbia created the opportunity for all participants to engage in the field activities that best suited their abilities. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

On Oct. 18, 2014, at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA) in Vancouver, British Columbia, the society hosted, for the first time, a field trip that was fully accessible to geoscience students and faculty with disabilities. The trip, which we led, is bringing attention to an often-ignored issue in the geosciences. Many students with sensory, physical or intellectual disabilities may be potentially discouraged from pursuing geoscience degrees when faced with course requirements that involve physically rigorous field-based learning.

In higher education, students are responsible for notifying their instructors when accommodations are needed. As such, instructors often aren’t aware that a student with a disability is enrolled in their course until the first day of class. For students with less apparent disabilities, requests for accommodations may not occur until several weeks into the term, if at all, impacting the ability of the instructor to provide appropriate accommodations. Courses that are not flexible enough to transition easily between different modes of instruction in order to accommodate different student needs and learning preferences, or even physical abilities, are difficult, if not impossible, to modify at the last minute. This is particularly an issue for courses with required field trips, for example, for which substantial planning is needed.

However, this does not have to be the case. For our trip, we engaged students who may otherwise have been marginalized to determine how best to design accommodations for both classroom and field-based learning environments. As we learned, many barriers common in geoscience instruction can be overcome by focusing on students’ abilities, rather than on their inabilities or challenges, thus creating a rewarding community of learning for all students.

From several locations at Garibaldi Provincial Park participants observed the debris fan formed from multiple landslides off of "The Barrier," a natural volcanic dam. Participants collected samples of cobbles from the floodplain to share with the participants who were unable to navigate the uneven terrain. Credit: both: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

The GSA trip included geoscience students and faculty from the U.S., U.K., Canada and New Zealand. Student participants included six geoscience graduate students and nine undergraduates, two of whom were nongeoscience majors; 14 of the 15 students self-identified as having a sensory, physical or cognitive disability. Thirteen geoscience faculty also participated — four of whom reported having a disability — along with two representatives from major international geoscience societies. Rounding out the group were a sign-language interpreter and a four-member team of trip leaders and research staff.

We visited six locations along the Sea-to-Sky Highway (BC Highway 99), which winds through the picturesque Howe Sound fjord — skirting steep, glacially carved slopes — between downtown Vancouver and Whistler, British Columbia. Each stop offered lessons on different aspects of the region’s geology, representing glacial, volcanic, fluvial, colluvial and tectonic processes, which, over time, have created both beautifully dramatic landscapes and the potential for severe natural hazards.

The variety of locations let all of the trip participants, regardless of their disabilities, participate in geologic field study through multisensory observation. The course’s design allowed a unique learning community to develop, and an opportunity for pairs of students and faculty to work together during the trip. Student-faculty pairs worked through planned activities at each field location, learning from one another and overcoming their individual accessibility issues. The teams each shared their views on the barriers to learning in the field and discussed methods and techniques for overcoming them.

As comfort levels within the learning community increased, participants began pushing the boundaries beyond the planned instructional objectives of the trip. At Garibaldi, several participants, including some with visual disabilities, experienced the direct observation of a floodplain with the assistance of their partners. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

Surrounded by 500 meters of granite cliffs near the Stawamus Chief, one of the largest granite monoliths in the world (at right, below), participants observed the local geology and glacial striations through sight and touch. Credit: both: International Association for Geoscience Diversity

We designed the trip to utilize “active learning” across a variety of locations, including panoramic overlooks and opportunities for close-up observations, which showed examples of several different geologic processes and rock types. After setting basic learning objectives, we organized the trip itinerary, which involved not only planning for instruction, but also the specific accommodations needed by the participants. To determine the latter, we surveyed the participants two months before the trip. No one understands the abilities and limits of the participants better than the participants themselves.

The most important aspect of the course planning and design was communication, early and often. Thorough communication with the participants during the course development stage allowed us to foster relationships with each participant and understand the diverse needs of the group as a whole. Once we understood the group dynamic and each participant’s abilities, we evaluated prospective field locations, scouting each a couple of weeks before the trip to determine which were accessible and exactly what activities would be possible. During this pre-trip scouting, we revised the initial field trip plan and, in two instances, completely replaced sites we’d originally chosen.

We needed to accommodate a wide diversity of sensory, physical and intellectual disabilities — from limited hearing and vision to reliance on a wheelchair to autism. Counterintuitively, this made the trip easier to manage. Everyone was focused on accessibility, no one was left feeling dissociated from the group, and participants not only self-advocated, but also advocated for others.

We knew that every field site would not be ideal for every group member, and it was important that the entire group be aware of this before the trip. As a result, participants worked together, without needing much direction from the trip instructors. For example, many participants brought rock samples to those with less mobility and described each location to those with limited vision. Instead of trying to find perfect stops, which probably didn’t exist given the range of abilities of the participants, we designed opportunities to provide multiple representations of content and determined how each participant could get the most out of each stop.

Since this trip included a range of expertise, from novice geoscience students to tenured faculty, and because we had students with learning disabilities, we tried to keep the jargon to a minimum, and we created both print and audio versions of the field guide. The audio version was recorded in chapters numbered according to individual field stops, so participants could easily listen to the guide during the trip. We also gave both the print and audio field guides to all participants ahead of the field trip, allowing them to review the material and prepare questions before the day of the trip.

Field trip instructors separated to work with participants in groups or pairs, ensuring that everyone remained actively engaged in the learning community regardless of their proximity to the geology at each site. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

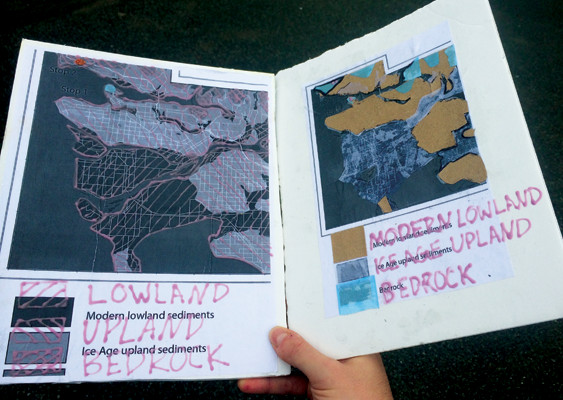

The trip leaders created tactile versions of the regional geologic maps used on the trip with materials such as fabric, various grades of sandpaper and puff-paint to represent different features. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

This debris fan could be seen from the road. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

In many ways, this trip was like any other geological field trip. We asked students and faculty to observe and make inferences about the physical processes that shaped, and continue to shape, each location. A few guiding questions helped participants put their observations into a useful framework. We purposefully didn’t lecture on the bus between stops; in this down time, participants engaged in discussions with their peers and reflected on the content and the environment at their own pace. However, the trip was also different in many ways from conventional field trips.

Some of these differences simply involved logistics. Compared to the fixed, often tight schedules of standard field trips, we planned to spend about an hour at each location and built extra time into the schedule in case it was needed at any stop. We also factored in time for unloading and loading participants who use wheelchairs. With such a large group, we ordered a second, smaller bus equipped with a lift system to accommodate participants who used wheelchairs or scooters, as well as those who had difficulty navigating the higher steps common in larger buses.

We also chose locations that would accommodate the accessible bus and chair-lift, and where the actual content of a field site was accessible. Unfortunately, this was not always possible; for example, reaching a rocky floodplain in Garibaldi Provincial Park, 70 kilometers north of Vancouver, proved a challenge for those with physical disabilities. In locations such as this, we made sure that geologic topics could be viewed and discussed from every location. We also asked more-mobile participants to act as “field scouts,” retrieving samples for full-group discussions.

We used both standard two-dimensional maps as well as tactile versions of the same maps, made of materials like fabric, sandpaper and puff-paint, to represent different features. All of the participants seemed to enjoy the tactile maps, not just those with visual disabilities.

To accommodate a participant with limited hearing, a sign-language interpreter was available during the trip. However, that didn’t go according to plan. We realized just days before the trip that the participant with the hearing disability, being an international student, was not trained in American Sign Language. However, the lead-time still allowed the interpreter to improvise and plan accordingly. Using a laptop, tablet or smartphone, the interpreter typed what was being discussed, keeping the participant involved in all conversations.

Integrating handheld technology provided the necessary accommodation for everyone to be involved in the learning community, which is often difficult for students with auditory disabilities. Although some accommodations for individuals with auditory disabilities, such as closed captioning or Communication Access Real-time Translation (CART) services, transcribe lectures and sometimes group discussions, individuals often miss out on informal and individual conversations. Having access to the interpreter provided a unique experience for this participant because he was fully included in conversations, discussions and lectures during all aspects of the trip — an active participant in the entire learning community.

“I am surprised how well [the interpreter] did,” the student told us later. “I can’t stress it enough that [everyone’s] help is what made this field trip so successful for me. [You all were] very mindful of every participant, which is what makes trips like these a success,” he said.

Pairing students with faculty was another way of accommodating the needs of every participant, as everyone had at least one person with whom they could discuss and share ideas, and who was looking out for them. After the field trip, one student said: “I never felt like I belonged” in previous field courses, but with this one, “there was this big communal atmosphere … and I felt like I was in the group.”

Through their diverse perspectives and abilities, the group bonded, establishing a community of knowledge and experience focused on making field-based learning accessible. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

Porteau Cove Provincial Park in British Columbia, one of the field trip stops, is located on the most southerly fjord in North America. Credit: International Association for Geoscience Diversity.

The trip was a “geotourism” style of trip with a variety of stops on a single day. However, it is certainly possible to accommodate other types of fieldwork, even mapping trips, with the use of relatively inexpensive equipment. For example, the TrailRider™ is an off-road wheelchair designed by the British Columbia Mobility Opportunities Society. Described as “a cross between a wheelbarrow and a rickshaw,” the TrailRider™, along with the assistance of two colleagues, would enable an individual with a mobility disability to navigate narrow or rough trails.

Nevertheless, barriers to field-based instruction will always exist beyond the control of the instructors or the participants. For this trip, the biggest difficulty was finding a bus with wheelchair accessibility. When we finally secured one, we discovered that the company we were renting the vehicles from had distance restrictions on certain buses for insurance purposes. Based on the location of the trip, the bus was not insured to travel out of the city. Although this was an obstacle at first, we were able to resolve it before the trip through early communication. We requested that insurance be purchased to extend the allowable distance the accessible bus could travel. However, even with the most detailed planning, a contingency plan is a must, and you have to remain flexible and patient — as is true with any field course.

The inclusive community of learning that manifests during an accessible field trip is unlike any other instructional environment. When designed according to the needs of the students, the experience will have an impact on all participants, including the course instructors. A learning experience that focuses primarily on the instructional objectives yet remains flexible enough to modify according to everyone’s abilities promotes an opportunity void of judgment where all participants can share their perspectives on and expertise of the content. Thus, rather than being hindered by concerns of acceptance and personal ability that might interfere with their learning, all participants are fully included and able to contribute to the learning community.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.