by Fred Schwab Tuesday, January 16, 2018

Fred's road bike traveled across the U.S. (including to the Badlands) with him and Claudia last summer. Credit: Claudia Schwab.

Claudia and I have been traveling together since we got married in February 1965. That summer and the following summer, she graciously agreed to be my assistant during summer fieldwork seasons in the Tetons and the Wyoming Overthrust Belt near Jackson Hole. By 1967, she resigned as my field assistant, but, thankfully, held on to her position as wife, traveling partner, photographer and biographer. Recently, she talked me into renewing our ties with the broader U.S. beyond our doorstep, so after spending the last dozen Julys in France watching the Tour de France, we spent the summer of 2017 rediscovering America, including our original fieldwork locales.

We set up guidelines: (1) Revisit some of our favorite national parks (the Badlands, Mount Rushmore, Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons and Dinosaur National Monument). (2) Choose other locations based on a seemingly random assortment of spots featured in books we’d read recently or movies we’d seen. (3) Spend two or more nights at each destination. (4) Don’t drive more than 400 kilometers in a day. (5) Use interstates sparingly. (6) No U-turns, except when mistakenly entering off-ramps to divided highways. (7) Stop for meals and overnights in small towns and bond with the locals.

I placed my road bike on the car roof, and on July 5, we shoved off from Lexington, Va., for an 11-week, 12,000-kilometer odyssey. Along the way, we saw again how great America is, and yet also how much it has changed in the past half century.

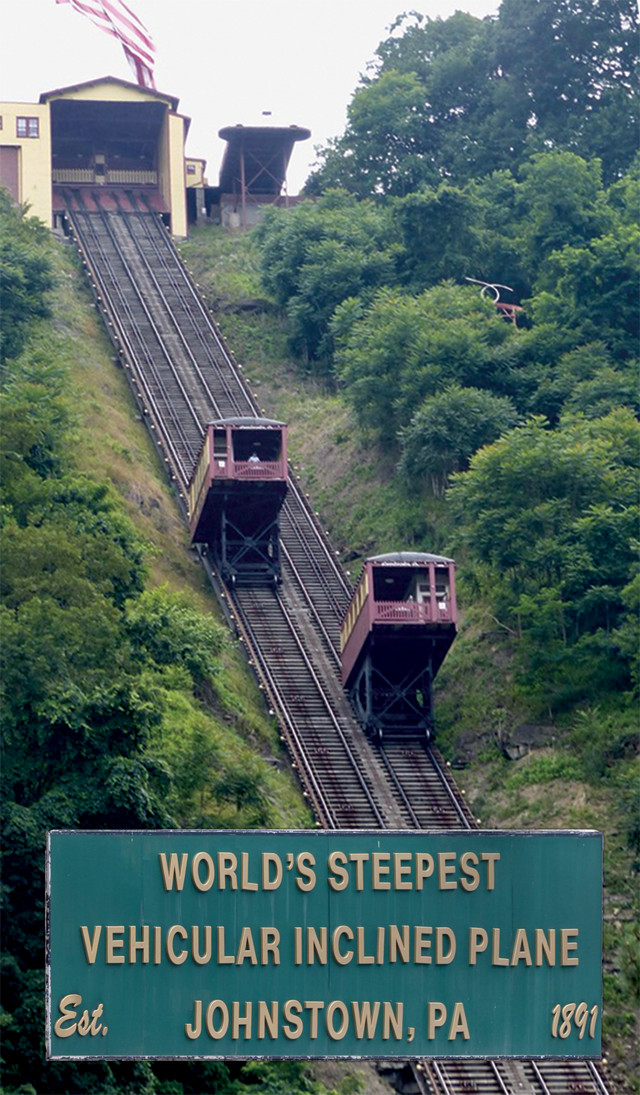

Claudia was reading David McCullough’s 1968 book, “The Johnstown Flood,” so our first stop was in Johnstown, Pa., a former steel town roughly an hour and a half east of Pittsburgh. Downtown Johnstown has the steepest inclined railway in the U.S. and is scattered with beautiful 19th- and early 20th-century buildings, many in disrepair but potentially restorable. The Cambria Iron Company (later Bethlehem Steel) of Johnstown once produced more U.S. steel than companies in either Cleveland or Pittsburgh. Today, the steel industry is gone, largely thanks to cheaper overseas competition, out-of-date technology and environmental regulations. Modest healthcare facilities and some defense contractors provide jobs, but throughout the city, you could sense the feelings of disappointment — even betrayal — that a way of life had disappeared, as well as anger that no one, including government, seemed to care. It seemed to us that many of the folks we encountered had simply surrendered, reluctant to seek new careers, especially if that meant changing locales.

The world's steepest vehicular inclined plane is in downtown Johnstown, Pa. Credit: both: Claudia Schwab.

Next, following Claudia’s reading list ("The Wright Brothers," also by McCullough), we motored on to the Wright Brothers bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, where they engineered the earliest airplanes, starting a fledgling aircraft industry. The early efforts from the dawn of aviation are displayed at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Forceoutside of town. How far that industry has come in one century is testament to human ingenuity!

Our next stop, in Oak Brook, Ill., just west of Chicago, contrasted mightily with Johnstown. This stop, home to McDonald’s Hamburger University, was my pick. I had my first McDonald’s food when I was about 16 years old in upstate New York — when their hamburgers cost 15 cents each — and I’ve always been fascinated by the company. Plus, we had recently seen the fascinating 2016 movie about Ray Kroc called “The Founder.”

At the university, the corporation educates its new franchisees on the business end of their investment in a park-like setting with a gorgeous Hyatt, a gigantic indoor pool and manicured bike trails (which is why we stayed there). As I finished my morning ride around the area, I was flagged down by a man on a cellphone, standing beside a semitrailer. He was an Eritrean immigrant who had recently come to America seeking a better life (but not winter) in Minnesota. This “new” American was searching for the McDonald’s loading dock, located behind a locked gate and an almost-too-narrow roadway. I welcomed him to the country, telling him our nation was built by immigrants like him (and my grandfather). He needed permission to enter and guidance as to whether or not his truck could make the trip, so after I spoke with the McDonald’s purchasing manager, I made a series of 1-kilometer bike trips back and forth to the loading dock, helping the driver obtain his permit to unload and assuring him he could make it down the roadway. I joked with the driver and the purchasing manager, wished them a pleasant day and left. It was one of those chance encounters, one of the small moments that make life interesting.

Fred and Claudia stayed at a Hyatt on the beautiful grounds of McDonald's Hamburger University in Oak Brook, Ill. Credit: Claudia Schwab.

That night, a Hyatt employee appeared with a bottle of wine, assorted cheeses and sausages, and best of all, a note from the McDonald’s purchasing manager, thanking me for the laughs, and telling me, “Today goes down as one of the best days in my career here!” The contrast between the forward-looking young Eritrean immigrant who moved to a new country for a better life and the resigned folks from Johnstown nostalgically recalling better times in the past was striking and depressing.

Fred stands in front of the Wright Brothers bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. Credit: Claudia Schwab.

Next, we spent three days in Madison, Wis., visiting the gorgeous campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison from which I received a master’s degree in 1963. We enjoyed a wonderful reunion with Bob Dott, my thesis advisor, and his wife Nancy, now retirement-home residents. Bob, approaching 90, has been a wonderful mentor and friend for more than 50 years; his slow concession to aging defied my illusion, typical of graduate students, that honored mentors remain forever young.

We crossed Wisconsin on Highway 18 to the bluffs of the Mississippi, and then continued on through Iowa. The lush green fields of soybeans and corn, flourishing on the glacial drift soils, testified to the richness of Mid-America. After three nights in Sioux Falls, S.D., which was built on and around the falls cutting into the more than a billion-year-old purple-violet Precambrian Quartzite, we reached the spectacular, but blazingly hot, Badlands National Park. Our small cabin fortunately was air-conditioned, and at 6 a.m. both mornings, I cruised through the park on my bike, watching the sun rise over the sculpted sandstones and shales. We visited the nearby Minuteman Missile National Historic Site and viewed an underground, deactivated missile — a chilling reminder of the Cold War.

The Minuteman Missile silo entrance, and an undetonated missile, at the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota provide stark reminders of the Cold War. Credit: both: Claudia Schwab.

After a compulsory stop at Wall Drug, and a brief look at Mount Rushmore, we stayed in Cody, Wyo., before proceeding over the spectacular Beartooth Pass. We rented a small cabin for two nights in Silver Gate, Mont. (where the nearest internet was several kilometers east in Cooke City). From there, we entered Yellowstone Park just to the south, using my National Park Service-issued Golden Age Passport, which I purchased 15 years ago for $10 and which is good for lifetime admission to all national parks. (Now going for $80 and known, less colorfully, as the Senior Pass, it’s still America’s best bargain!)

Unlike many tourists, Fred and Claudia did not get out of their car to take selfies with Yellowstone's ubiquitous buffalo. Credit: Claudia Schwab.

Yellowstone was jammed with visitors eager to learn about their planet and its wildlife. About 4.3 million people visit each year, with close to a million in July alone, and nearly as many in August. There were 30-minute waits for parking at the well-known hot springs and the Upper and Lower Falls. Bison herds backed up traffic for a couple of kilometers between Lake and Canyon Village. I biked up Dunraven Pass from Canyon Village, narrowly avoiding being decapitated by side mirrors on vans struggling up the same gradient.

The Grand Tetons and Jackson Hole showed 50 years of progress — if you want to call it that — since the mid-1960s when I did my fieldwork there. Jackson Hole now has 11,000 residents, compared to fewer than 2,000 in 1965. Teton County was ranked as the wealthiest county in the United States based on the 2012 mean adjusted gross income ($296,778). The disparity in our country — heck, even just among towns in Wyoming — between the “haves” and “have-nots” is pronounced. Our return home via the Colorado ski resorts of Breckenridge and Telluride underscored this observation.

Telluride, Colo., as viewed from a gondola above the town. Credit: Claudia Schwab.

The voyage across our homeland overwhelmed us with the beauty and diversity of its landscapes and people. It’s clear that many Americans are evolving but are still nostalgic for the past, ill-at-ease with the present and uncertain, even fearful, about the future. We are torn between open-mindedness and insularity: toward the government, each other and the wider world. Where we go from here is unknown. But we can all benefit from the perspective gained by taking a closer look at our wonderfully diverse country, from the lush fields of the midcontinent to the soaring peaks of the Tetons, and its people, from the Johnstown residents to the Eritrean immigrant. The reward would be a far wider — and greater — appreciation for where this country has been, and where it’s headed.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.