by Fred Schwab Thursday, April 20, 2017

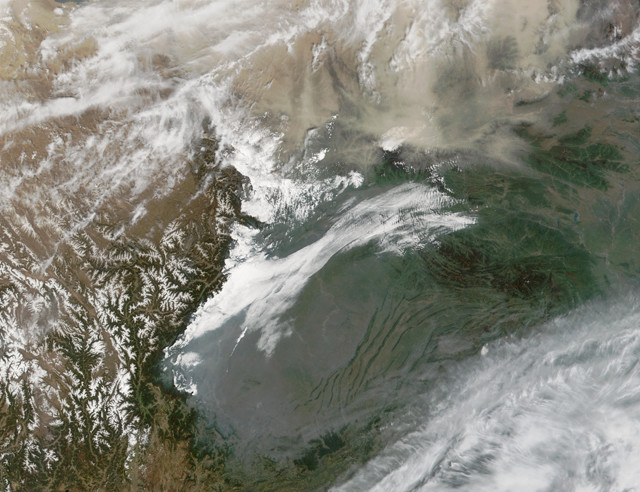

Satellite photo of the Sichuan Basin — in Sichuan Province, north-central China. The pollution from the urban and industrial centers of the Sichuan Basin in Sichuan is visible at the bottom of the image. Credit: NASA, public domain.

My obsession with China began when our son Jeffrey moved there 10 years ago. Since then, we have visited him a half dozen times, and the change that we have witnessed in the country in that time has been staggering.

Lanes once filled with bicycles are now jammed with cars. China is now the largest automobile market in the world. Of the roughly 66 million cars registered or sold worldwide in 2015, 21 million were in China. In 2005, by comparison, the Chinese market for new cars numbered only 4 million vehicles, according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers. In China, far-flung cities and industrial sites are now linked by a 22,000-kilometer-long electrified high-speed rail system. The population of 1.4 billion people is increasing, thanks to the lifting of the “one child” law, and the growing population is eager to educate and innovate. When Jeffrey moved to China, 11.1 percent of the international student population in the United States was Chinese (Indian students were first at 11.8 percent). In 2014, 31.8 percent of the international students were Chinese, with EU students second at 9.5 percent, according to a March 2016 Wall Street Journal article.

To maintain economic expansion, China is moving from a managed economy focused on infrastructure to a market economy focused on consumerism and innovation — and the strains have been enormous. The rapid migration of rural Chinese to the urban coastal region has generated unbridled growth. About 55 percent of China’s 1.4 billion people are now city dwellers, compared with less than 18 percent 35 years ago. A new supercity of 130 million (40 percent of the population of the entire U.S.) will combine the cities of Beijing and Tianjin with Hebei Province, a Kansas-sized area connected by high-speed rail.

One constant in China, we have found, is polluted air and water. Jeffrey dons a facemask as he heads out to perform improv comedy (in Mandarin)!

Many of China’s problems stem from its dependence on coal. Coal production and consumption exceed that of the rest of the world combined. Coal burning produces about two-thirds of China’s electricity, for which demand increased almost 17-fold from 1980 to 2012. China consumes roughly four times as much coal as the United States annually, and produces double the carbon dioxide emissions. In 2013, roughly 400,000 premature deaths in China were attributed to the burning of coal.

But China is finally doing something about it — setting targets to limit greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel consumption, partly in accord with the December 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. China recently announced its intention to increase the amount of energy from renewable sources from the present 11 percent to 20 percent by 2030. Presently, China’s coal-burning plants operate at roughly half capacity, yet in 2015 permits were issued for 210 more plants. However, on April 25, 2016, China announced its intention to rein in this program, as a consequence of the Paris Agreement.

Options for alternative energy sources include increasing the number of nuclear power plants (now 30). Twenty-one additional plants are under construction, with another 135 reactors originally proposed. Nuclear power generates roughly 1 percent of the greenhouse gases produced by burning coal. The Chinese will also greatly expand hydro, solar and wind power.

Mining and burning coal for electricity consumes lots of water: Worldwide, coal plants consume enough to provide drinking water for 1 billion people. This will double if the proposed coal-fired plants actually come on line. The coal industry consumes half the industrial water use in China, and between 10 and 20 percent of total consumption. But water availability isn’t the only issue. China is besieged by polluted rivers, the result of dumping untreated industrial and agricultural waste into river systems. Aquifers, especially shallow ones in the arid north that supply two-thirds of the water for domestic use, are especially stressed. Some 280 million Chinese drink unsafe water, and half the waterways carry water unfit for even human contact. The city of Beijing, together with surrounding Hebei Province, is investing in a desalination project in the city of Tangshan (completion, 2019; cost $1.1 billion). It will eventually supply 1 million tons of freshwater daily, roughly one-third of the present consumption in Beijing.

The Chinese desalination project is overshadowed by the South-North Water Diversion Project, a scheme that involves three artificial channels bringing water from the Yangtze River and tributaries to northern China metropolitan areas. There are serious ecological and economic concerns about the impact of this project on the environments and populations affected by these waterways. Yet water has to come from somewhere: Beijing’s population continues to explode by half a million per year. It presently has about 100 cubic meters (20,000 gallons) of water per person — one-tenth of the U.N. standard for water availability above scarcity levels .

Air and water pollution, water scarcity, a slowing economy, urbanization, and a growing and progressively wealthier population all create a whirlwind of change. China continues to fascinate and intrigue!

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.