by Ward Chesworth Friday, January 30, 2015

“I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest.” – Huck Finn

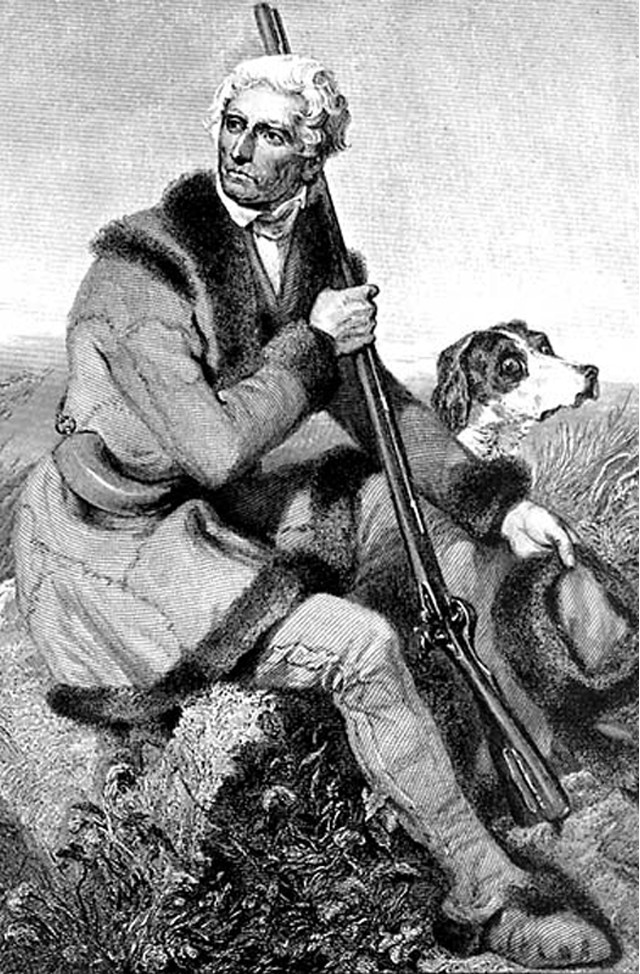

Engraving of The elderly Daniel Boone hunting in Missouri by Alonzo Chappel (c.1861). Credit: Public Domain.

In 1799, Colonel Daniel Boone found Tennessee’s population density of 10 people per square mile irksome, so he moved to land west of the Mississippi. Boone’s fictional counterpart was James Fenimore Cooper’s hero Natty Bumppo (aka Leatherstocking), who left his stomping grounds alongside the Great Lakes and walked all the way to the Pacific to get away from the sound of trees being felled by homesteaders. He even got to the ocean ahead of Lewis and Clarke — not bad for an 80-year-old. I wonder what he would have thought of a future that would see Las Vegas, the largest city founded in the 20th century, built in the arid lands of the West?

Leaving fiction aside, the real push for western settlement came in the second half of the 19th century. “Go west, young man” was the siren song, which appealed to the national myth of the rugged pioneer. By that time, the frontier was roughly the hundredth meridian, where the average rainfall was less than 25 centimeters a year. In other words, those young men were being lured into a desert. Any pioneering skills they had were Eastern skills, great for clearing forest and turning it into farms in a rainy climate, but useless for settling the arid West. John Wesley Powell saw this clearly in 1879 when he tried to warn Congress of the folly of promoting westward migration with his classic “Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States.” But by then a booster-lobby of railroad men, bankers and land agents, all with dollar signs in their eyes, was too strong even for Powell. So the new pioneers were sent west lacking the smarts to survive.

In the movie, “The Rainmaker,” the con artist played by Burt Lancaster promises to bring rain to a drought-stricken Kansas farm for $100. The boosters of western settlement, however, believed in a different rainmaker. “Rain follows the plow” they parroted, following a now-discredited idea that if you break the land and plant crops they will release water from the soil, clouds will form, and it will be raining cats and dogs before you can find shelter.

Nothing could be further from the truth. In arid lands the plow is arguably the stealthiest and most successful weapon of mass destruction ever invented. Desertification and salinization, not rain, are what follow the plow in naturally dry lands. Look at Iraq, where western civilization began and where it took a couple thousand years for desertification to destroy Old Testament cities like Nineveh and Ur of the Chaldees. Today, capitalist or communist, we are more efficient. The Midwestern plains harvested their grapes of wrath and turned the land to dust after two or three generations of cultivation, and the Aral Sea region became a desert thanks to a plan to harvest its water to grow cotton in the last 50 years of Soviet rule.

Techno-optimists are the modern-day boosters. With big dams and the technology to tap large aquifers, we can bring water to the desert and make it flourish. For the tourists who visit Las Vegas and never stray far from the air-conditioning of hotel and casino, it’s easy to forget that their playground is part of a desert. But with our climate changing, reality seems ready to reassert itself. How long will there be a snowpack in the mountains to feed the Colorado River and top up Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam? How long before the aquifers of fossil water are pumped dry? And looking farther afield, how long before vested interests and engineering hubris convince political and financial leaders that water diversions from the Great Lakes make sense? Would that mean a future “Aral Sea” disaster for the U.S. and Canada?

Is it scaremongering to ask such questions? Perhaps, but only if you are a cockeyed optimist. I believe that it’s just part of the due diligence of living responsibly on a vulnerable planet. Arid lands are readily sustained by regular geological processes — but only as arid lands. When we try to convert them into wetter biomes we have to expend energy and materials in amounts that are unsustainable in anything more than the short term.

I’m with Bernard DeVoto, the historian of the American West, who believed that our unwise use of resources in places like the arid U.S. Southwest could quickly return a region back “to the process of geology,” and I suspect that the return of the desert to Las Vegas by the end of the 21st century is a reasonably sure bet. Go see what odds you can get in the casinos there.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.