by Ward Chesworth Monday, August 4, 2014

©J.M.Lujit, cc-by-2.5-nl licentie van auteur.

You wake up hungry in the middle of the night and remember that chunk of Spam in the refrigerator. You sneak down, ease open the fridge door and find that, embedded in said Spam, is a set of dentures. How do you react? With a Brando-esque utterance of “the horror, the horror”? Of course not; you have scientific smarts to fall back on.

At first, you think that the smile on the teeth looks enigmatic. Maybe a peckish Mona Lisa hopped over from Paris on the red-eye? Sober reflection tells you that’s ridiculous, and that the smile isn’t really enigmatic after all. It’s more of a dirty grin. That’s when you say “Gotcha!” (or “Eureka!” if you grew up in the Hamptons with Jay Gatsby) — the culprit was Grandpa. Pushing deduction to the limit, you conclude that the unhygienic old felon is a carnivore.

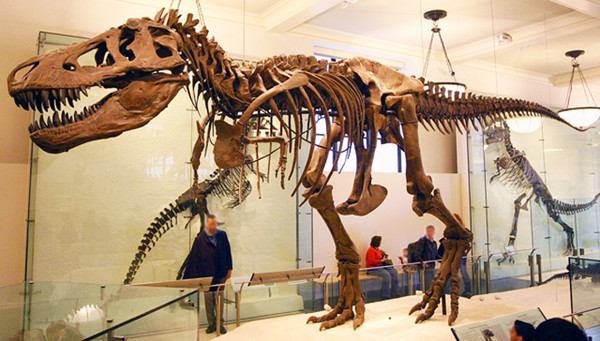

That, more or less, is the argument advanced by Robert A. DePalma II, of the Palm Beach Museum of Natural History in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and colleagues in their recent study of a Tyrannosaurus rex tooth published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I’m no paleontologist, so I was unaware that T. rex was in danger of losing its street cred as the scariest meat-lusting hunter of all time. The lumbering giant was being dissed in certain circles as a sneaky scavenger, a kind of reptilian hyena.

In any case, the authors didn’t find the tooth embedded in Spam, but in a tail vertebra of a potential meal, an herbivore called a hadrosaur that appears to have been running for its life. Thanks to the sleuthing of DePalma et al., T. rex has its credibility back, though in this instance he failed to make the honor roll. The embedded tooth had an overgrowth of new bone, telling us that the prey got away and lived on. It’s an early example of a long tradition that culminated in the half-hour TV nature shows made by Walt Disney in the 1950s. Walt taught a generation of kids that the sweet little bunny always escaped down the rabbit hole before the nasty fox grabbed it. At least _T. rex _got a nibble.

As you might expect, Sherlock Holmes was the most famous pioneer of using geology as a forensic tool. Dr. Watson records that the Great Detective could tell different soils from each other, when seen staining the cuffs of a man’s trousers, at a mere glance. Truly amazing! After a professional lifetime of study, I still can’t do that. Given the same evidence as Holmes, I’d be unable to place a guy at the scene of a crime. The issue is moot, anyway; nobody wears pants with cuffs anymore.

Years ago, however, I had a brief foray in geo-detection. The dean of biology at the University of Guelph, Keith Ronald, wanted me to find out how far afield a particular seal had wandered on the basis of a piece of rock found in its stomach. I sectioned the rock and examined it by polarizing microscope. It was dark-colored and fine-grained with plagioclase and olivine rimmed by orthopyroxene set in a glassy groundmass that contained a small amount of tridymite — clearly a tholeiitic basalt. Keith was delighted to have it definitively named, but then asked where it had originated. I told him that as the common volcanic rock of the ocean floor, it could be from any of the Seven Seas. “Well that certainly narrows it down,” he said. After he left, I realized he’d forgotten to thank me.

Sexton Blake achieved much better precision. He was a down-market version of Sherlock who wore a bowler hat instead of a deerstalker and who figured in the popular escapist reading of British railway travelers in the early part of the 20th century. One of his adventures tells of how he pinpointed his exact geographical position despite lying bound and gagged on a villain’s yacht off the British coast. When a wave washed a lump of rock on board, it fell to the deck without the clunk of a regular rock. On the contrary, it rang out like a bell, and the trussed-up gumshoe said, “Aha, phonolite, from the Greek for ‘sounding stone,’ a volcanic rock dominated by alkali feldspar with minor amounts of feldspathoid. Found only in these islands at the base of the Wolf Rock lighthouse, 7 kilometers southeast of Land’s End, Cornwall.” Nowadays of course, you could get the answer instantly by GPS and avoid all the pedantry.

Not all beliefs can be suspended, as with another mystery about T. rex. What was the king of the tyrant lizards doing in “Jurassic Park” when he didn’t evolve until the Late Cretaceous? Maybe some corporate muck-a-muck decided that a book about dinosaurs without the scariest dinosaur of all, or with the daft title, “Cretaceous Park,” just wouldn’t sell. Personally, I think that Michael Crichton just got his science wrong, as he did in 2006 when he spoke to the oil industry on climate change.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.