by Ward Chesworth Thursday, April 6, 2017

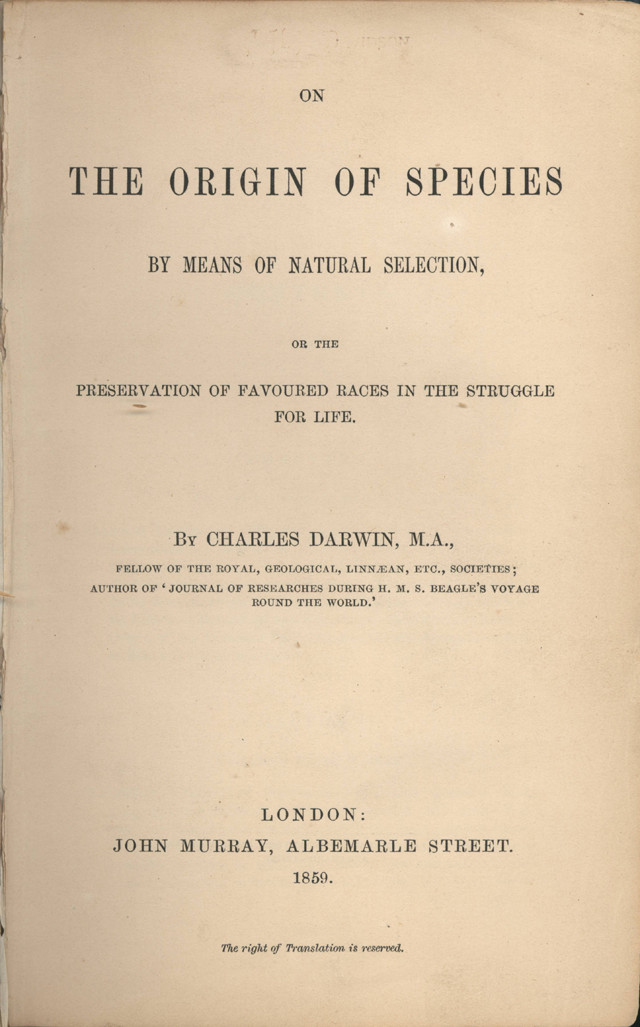

The title page to Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of the Species", published in 1859. Credit: Public Domain.

By the time I was 12, I had identified the greatest writer in the world. His name was Edgar Rice Burroughs and he wrote adventure stories about an ape-man named Tarzan. Burroughs described him as having a “straight and perfect figure muscled as the best of the ancient Roman gladiators must have been muscled, and yet with the soft and sinuous curves of a Greek god.” You could see at a glance his “wondrous combination of enormous strength with suppleness and speed.” Tarzan was human, but he’d been orphaned in Africa and raised by a she-ape in the jungle. That made him an ape-man for sure in any kid’s estimation. The first Tarzan story appeared in 1912, but the most significant date for ape-men was half a century earlier, in 1859, when Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” which encouraged the search for a real ape-man called the “missing link.”

The missing link was a supposed stepping-stone in our evolution from an ape-like ancestor. Early artists’ impressions generally depicted him as a squat, hairy figure with a prognathous jaw and knuckles that scraped the ground. German anthropologist Ernst Haekel gave him the name Pithecanthropus (“ape-man” in scientific Greek) in 1866, though an actual fossil wasn’t found until 1891 when Eugène Dubois discovered a skullcap, femur and a few teeth in the East Indies. Dubois called the species Pithecanthropus erectus (the “upright ape-man”), but it became better known as “Java Man” after the island on which it was found. Later it was renamed Homo erectus and the Pithecanthropus designation became obsolete.

Soon, missing links were turning up all over Asia, Africa and continental Europe, but nothing was found in the Anglo-Saxon world. In 1912, the same year Tarzan first appeared, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson unearthed the skull of “Piltdown Man,” said to be 500,000 years old, in southwestern England. Unfortunately, it was a fake, although that wasn’t discovered until 1949, when new dating techniques unequivocally showed that the bones were modern. Worse still, the bones weren’t even all human: The remains had been cobbled together from the skull of a modern human and the lower jaw of an orangutan. To be fair, Dawson’s find, although a fake, was technically a genuine ape-man!

The first American “find” was similarly bogus. In 1922, solely on the basis of a worn fossil tooth, paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn declared the discovery of the first anthropoid ape in Nebraska, where influential congressman and avowed anti-evolutionist William Jennings Bryan held sway. Briefly, Osborn toyed with the idea of naming the new fossil after Bryan but eventually settled for Hesperopithecus (the “western ape”), while to the populace it was known as “Nebraska Man.” Sadly, Nebraska Man never existed. Osborn’s colleague William King Gregory concluded that the tooth likely came from an extinct peccary, a kind of pig.

The aforementioned William Jennings Bryan went on to represent the winning, anti-evolutionist side of the argument in the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925. The trial convicted biology teacher John Scopes of violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which forbade the teaching of human evolution in any state-funded school. The verdict was later overturned on a technicality, but the trial had sparked interest across the country. William Allen White, editor of the Emporia Gazette in Kansas, decided to check at his local library to see whether this new popularity was reflected in books borrowed. He was surprised to find no spike in requests for books on evolution, but found that all six of Burroughs’ Tarzan books owned by the library had been continuously checked out since the trial began. The novels had the “biggest waiting list of any books in the library,” the librarian told him.

By the time of the Scopes Trial, Tarzan was already appearing in silent movies, with the incongruously chubby Elmo Lincoln as the title character. The movie-Tarzan I got to know was the role’s greatest interpreter (in my humble opinion), the magnificent Johnny Weissmuller. As a five-time Olympic gold medalist in swimming, he had the straight, perfectly muscled figure that Burroughs had described.

The big contribution that Weissmuller brought to the movie was the ululating yell he invented for Tarzan, as he swung through the trees on lianas that always seemed conveniently at hand. The yell is still used in modern movie versions, and I could once do a reasonable copy of it. I gave up the practice when it began to hurt my aging vocal cords. Weissmuller must have had a similar problem when he made the transition to television in the late 1950s, because he became yell-less. Worse still, he’d become a little paunchy by then, so they stuck him in a safari suit and called him “Jungle Jim.” It’s the clearest case of retrograde evolution in primate history.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.