by Carolyn Gramling Thursday, January 5, 2012

A Spore creation explores the primordial soup of the Cell phase.

In the Creature phase, players are constantly tweaking their creations, adding or removing wings, eyes or limbs.

Spore's Tribal phase involves defending your species' hut, fire and food.

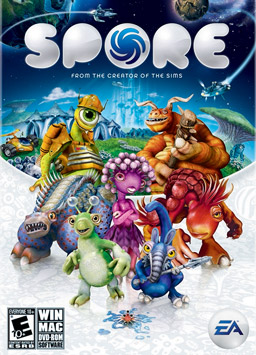

Spore Electronic Arts

I’m no evolutionary biologist, but I’m pretty sure that you can’t just add a horn or an extra ear to your own body whenever you feel like you need a leg up on the competition, so to speak.

That minor quibble aside, Spore, the newest Electronic Arts game by Will Wright, the creator of SimCity and The Sims, does effectively demonstrate the central tenet of evolution: that such biological tweaks, additions and alterations (evolved over considerably longer time spans, however) can make a significant difference to a species’ survival. Plus, you can make really cool-looking creatures, one extra eye at a time.

Spore, which was released in the United States on Sept. 7, has been eagerly anticipated; the game includes a suite of tools to enhance the game’s communal experience, including the “Sporepedia,” a social networking tool that lets players share their fantastical creatures with each other.

In Spore, if you’re a successful creature and your evolutionary “choices” are sound, then — after chomping, fighting, warbling and/or dancing your way through interactions in a primordial soup, idyllic forest and Bronze Age-ish early village — you’ll ultimately find yourself enmeshed in a highly civilized, full-blown space race. Full disclosure: I didn’t get that far.

The game passes through five stages of evolution: Cell, Creature, Tribe, Civilization and Space, each of increasing length: The Cell stage lasted perhaps 15 minutes when I played it, just long enough to eat assorted floating ooze, dodge ugly bug-eyed monsters and grow my creation to a respectable size.

Oddly, when passing from stage to stage, players don’t have to stick with their original creations. For example, when passing from the Cell to the Creature stage, you can completely overhaul the creature you’ve just shepherded out of the slime — in addition to adding legs, you can alter everything from eyes to color to dietary preference (I found omnivore to be the most convenient, in terms of finding food). This stage is all about deciding whether other species are friend or foe, and either courting or fighting them, depending. In the Tribe stage, you control a group of the species, rather than an individual, and develop tools. In the Civilization stage, your species builds cities and populates a planet; along the way, you determine what drives them: warfare, religion or commerce. And then there’s Space, by far the longest stage, in which your species extends its reach across the galaxy, terraforming and colonizing worlds for as long as you can stand it.

As with other Sims games (and, one might say, evolution), Spore is all about open-ended possibilities and far-reaching choices that can take the game in umpteen directions. Some of the heady variety comes not just from the anatomical decisions that you make — hm, I think I’ll give my little buddy stalk-eyes and opposable thumbs — but from more subtle social choices as well. At the Creature stage, many of the surrounding species were potential foes; but being a peaceful person who abhors fighting, I decided to dance my way into these strangers’ hearts, mimicking their songs and movements to win them over. That, it turns out, designated me as a “social” creature.

Unfortunately, those alliances didn’t carry forward into the next (Tribal) stage. That was an interesting point: Each stage was essentially standalone, rather than a progression of choices stemming from the initial stage. That flexibility allows players to take new tacks midway through gameplay — if being a friendly herbivore wasn’t working out for you or became too boring, you could try being an aggressive warlike society next time around — but was also somewhat frustrating. I think it would have been effective and interesting to give the option of continuing players’ choices from stage to stage, rather than starting each stage anew as a relative blank slate. I won’t argue that it’s an issue of realism, since realism doesn’t precisely enter into it; The evolutionary leap from one “stage” (groups of creatures ringed about a central nest) to the next (tribes with spears and cooking fires) is so massive that it’s akin to wiping the slate clean anyway. But it would make for interesting gameplay.

And although science-infused, the game is clearly entertainment first, grounded by certain educational underpinnings and big evolutionary questions. Scientists have noted with reservations that the piecemeal creature-creation doesn’t much resemble actual evolution. But as Wright, its creator, noted in a New York Times story Sept. 2, he wanted Spore “to communicate grand patterns of evolution,” such as the balance between competition and cooperation and the potential importance of a tiny evolutionary advantage, but in a much more accessible time frame than the span of millions upon millions of years.

It doesn’t take millions of years to play the game (although at times it seemed that way). But Spore’s myriad evolutionary possibilities have the potential to be an endless source of diversion, both for gamers and for evolutionary biologists who sometimes wish they could just speed things up a little.

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.