by David B. Williams Monday, February 2, 2015

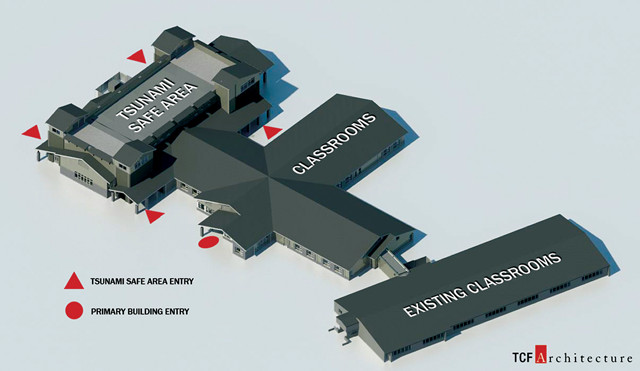

A tsunami evacuation refuge — the first of its kind in the country — will soon occupy the roof of a newly built gymnasium at Ocosta Elementary School in Westport, Wash. Credit: TCF Architecture.

In April 2013, voters in two counties on Washington’s Pacific coast approved a $13.8 million bond for school renovations in the shared Ocosta School District. The bond had failed twice before, but this time — when the measure included funds to construct a “tsunami refuge for students, staff, and community” — it passed with the support of 70 percent of voters in Grays Harbor and Pacific counties. It will be the first structure of its kind in the country.

The open-air tsunami evacuation refuge will be the roof of a newly built gym at Ocosta Elementary School in the coastal town of Westport, and will be able to hold more than 1,000 people. Construction began recently, culminating nearly two decades of preparatory work by a multiagency team, says team member Tim Walsh, chief hazard geologist at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR). He reported on the effort at the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting held last October in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Walsh conceived the idea for an evacuation structure in 1995 as part of the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP), which brought together federal and western state agencies. He was particularly concerned about the vulnerability of Washington state’s southern coast to tsunamis, because this area is home to many people living in communities built on low-lying sand spits with little or no high ground to which to escape. Sitting next to the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ), which last produced a magnitude-9-plus earthquake in January 1700, these coastal communities could be inundated in less than 30 minutes following a sizable quake on the fault.

The NTHMP’s first step was to prepare tsunami hazard maps, which illustrated the extent of the hazard posed by the 1,000-kilometer-long CSZ. The team also began to study the feasibility of designing structures that could survive high magnitude quakes, which led to the idea of erecting vertical evacuation facilities in hazard-prone areas such as the Washington coast. Working with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, Walsh and others in the Washington DNR designated the effort “Project Safe Haven.”

Options for an evacuation facility included towers, buildings and berms; potential facilities had to be cost-effective, provide space for many people, and serve multiple purposes. “We could never afford a single-use structure that might be used for just 12 hours every 500 years,” Walsh says. Public buildings, particularly schools, were the best possibility because “they are present in virtually every community and typically occupy a large space,” he says. So when the prospect of renovations at Ocosta came up again, Walsh knew it would be a good opportunity.

He was aided by Paula Akerlund, the school district’s superintendent, who championed the refuge idea. A community survey had shown strong support for it, so Akerlund worked to have the structure included in the revised renovation bond in time for the April 2013 vote.

This past December, crews began construction on the gym atop a small hill, which will put the rooftop refuge 17 meters above sea level and 8.5 meters above ground level. Studies show that this elevation will place the refuge above the highest predicted tsunami waves, Walsh says. Stairwells in four external towers at the building’s corners will allow access to the roof at all times of day. In addition, deep pilings, concrete shear walls and concrete-encased steel columns have been designed into the gym to resist earthquake shaking and wave inundation. Construction is expected to be completed in time for the 2015–2016 school year.

Walsh says his team intentionally avoided labeling the structure, which is designed to provide a safe haven for a maximum of 12 hours, a “shelter” as that would imply the refuge will feature running water and toilets, which it will not have.

Both Walsh and Akerlund say they have been contacted by many individuals and communities interested in pursuing similar projects, including building a berm near Long Beach Elementary School, about 40 miles south of Westport. “People are certainly aware of tsunami risks,” Walsh says. “What’s different now is the increased urgency, particularly following the major tsunamis we’ve had in the past decade.”

© 2008-2021. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written permission of the American Geosciences Institute is expressly prohibited. Click here for all copyright requests.